Malorie Blackman: “As a teenager, I never read books by black authors”

My mom and dad told us about Barbados. And when relatives came over, they talked about “back home in Barbados” and so on, but these were just stories that I listened to with interest. I myself didn’t go to Barbados until I was in my early 20s. Whenever I asked my mother specifically about Barbados, she said it was a while ago. Later, she told me more about her childhood.

When I went to Barbados, I felt less connected than I had hoped. The experience was somewhat marred by the fact that I had booked a package holiday and I was the only black person on the plane. And when we got off, I was the only customer they pulled aside to look in my luggage. So it wasn’t a great start. But then I had two wonderful weeks. It was just so nice to know that this is where my parents were born and that this is where all the places I had heard so much about were. But I expected to feel like, “Yeah, I’m coming home.” And I didn’t.

I would tell my teenage self to accept herself as she is and not be ashamed of it. I was strange. I was weird. I did things like if I left the house on my left foot one day, I had to leave on my right foot the next. I didn’t walk on the cracks. When I sat reading, I didn’t notice that I was rocking back and forth. I took everything too literally and didn’t understand a lot of jokes. I thought, Why is everyone else laughing? I don’t get it. Why did you say that? I took people and words at face value. I tried to suppress my instincts—I knew other people thought, felt, or acted differently. It wasn’t until years later, when I read about neurodivergence, that I thought, Ah, that’s just me. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that, and I should really embrace that part of me.

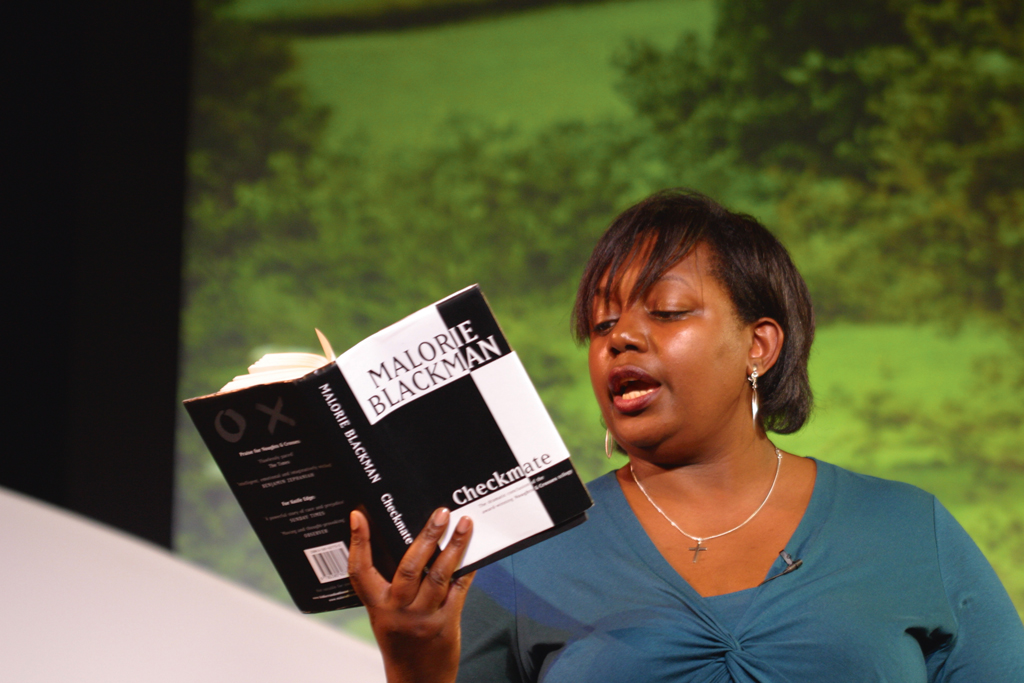

I don’t think my younger self would have believed that I would actually make a living doing something I never even thought about as a teenager. I have never read books by black authors or with black characters. The first play I read with a black character was Othello when I was 17. The first book was The colour purpleand that was when I was 21. Although I had been writing for myself for my own enjoyment since I was eight or nine, it never occurred to me that I could actually make a living at it.

If I could go back and talk to my younger self, I would say: Don’t be afraid to take risks. If you think you know what you really want to do, just do it. That was a lesson I learned after a while. And don’t be afraid of being laughed at. Some people might laugh at you if you say you want to do that. Just do your own thing.

The first big breakthrough as an author came when I finally got a publication after 82 rejection letters. I was 28. Eight or nine of my books were rejected one after the other. Years went by and everyone still said no. But I still got to work and kept going. As soon as I finished one book and sent it off, I immediately started on the next one. I always had four or five ideas in my head. Then I got a letter from Live Wire Books saying, “Dear Malorie Blackman, we would love to print your stories.” After all those rejection letters, I felt really great, completely happy. Because I started to wonder if I was wasting my time. I made a deal with myself that if I got 100 rejection letters, I would reconsider. But I only got 82. Then later I had a real breakthrough with Tic-Tac-Toebecause that was chosen as a BBC Big Read. And it won the Federation of Children’s Book Award, which is voted for by tens of thousands of children. That really changed everything for me.

If I could have one last conversation with anyone, it would probably be my brother because he died during the Covid pandemic. We weren’t close and I kind of regret that. It would have been nice if we had sat down and had a real conversation about his life and just been closer than we were when he died. That would have been good.

Stories do a great job of building empathy in people. They give you the opportunity to put yourself in someone else’s shoes for a while and see life through someone else’s eyes. One of my books, Boys don’t cryhas a character who is gay, and I have received letters from teenagers who say the book helped them come out to their parents. I have received letters from people who are dealing with the unrest in Tic-Tac-Toe with people saying, “Ah, you’re actually talking about the situation in Ireland, between Protestants and Catholics.” I love that: readers relating it to their own situation. That’s why I think there needs to be more emphasis on the arts in schools. I’m not saying science subjects aren’t important, of course they are. But I think this emphasis on STEM is the wrong way to go. You can understand yourself and others better through theatre and music and books and films. We ignore them at our peril, because they are vital – to our relationships and our mental health.

I was thrilled that I was even considered for writing Doctor Who. And the fact that I got to write about Rosa Parks – she’s such a hero, I just think she’s so incredible. She had so much courage to do that (Parks was a black woman who refused to give up her bus seat to a white passenger in segregated Alabama). And she knew what the consequences would be; she lost her job, she got death threats, she had to move to another state. So writing about her was a dream come true in itself. That was definitely one of my happiest moments, just being in the writers’ room of Doctor WhoBeing part of that process. When I look back, there are so many moments where I had that “pinch me” moment. Am I dreaming? Because that’s a really beautiful dream.

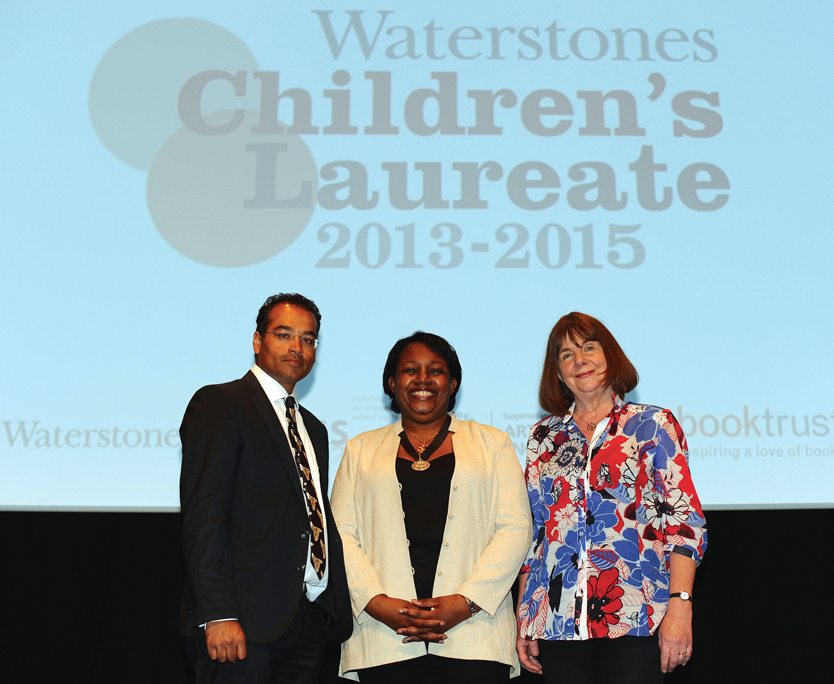

Malorie Blackman is an ambassador for Cardboard Citizens. Her autobiography Just Sayin’ is out now (Merky, £10.99). You can buy it from The Big Issue shop on Bookshop.org, supporting The Big Issue and independent bookshops.

Would you like to share a story or share your opinions? Get in touch and tell us more. Big Issue exists to provide homeless and marginalised communities with opportunities to earn an income. To support our work, buy a copy of the magazine or download the app from App Store or Google Play.