Last year, I met members of a children’s book club in Gurugram to discuss a picture book I had written on children’s rights. When we were discussing the right to education, one teenager said, “If poor children don’t go to school because they have to fetch water or work, they and their families are choosing not to get an education. How can they complain?”

I was reminded of this when I read Abhijit Banerjee’s foreword to the recently published book by economist Esther Duflo and illustrator Cheyenne Olivier: Bad economic situation for childrenHe writes: “… the discussion about the poor is wrong in the world because it ignores how hard it is to be poor and therefore blames them for their own life problems.”

Esther Duflo | Photo credit: Bryce Vickmark

The English translation was originally published in France and released in India last week by Juggernaut. Five of the stories have been translated into Hindi, Bengali, Kannada, Tamil and Marathi. Pratham Books will also publish the story as individual picture books.

Expansion of the S-curve

For their life’s work, with which they sought to understand the specific problems of poverty and find solutions, the couple Duflo and Banerjee, together with the American economist Michael Kremer, received the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2019. A few years earlier, their research was also published in a book: Bad Economics: A Radical Rethink in the Fight Against Global Poverty (2011), which reveals why the poor, despite having the same goals and abilities as everyone else, end up living very different lives.

“I realized that it was the true stories that attracted people in Bad economyand that they understood certain concepts after reading them,” Duflo, a professor of economics at MIT and the Collège de France, tells me in a Zoom conversation. She remembers reading books about poverty as a child; they stuck in her mind, even though they were full of stereotypes. But the fact that they stuck in her mind sparked in Duflo a desire to write for children, an audience for whom very little has been written on the subject of poverty..

Bad economic situation for children Book cover

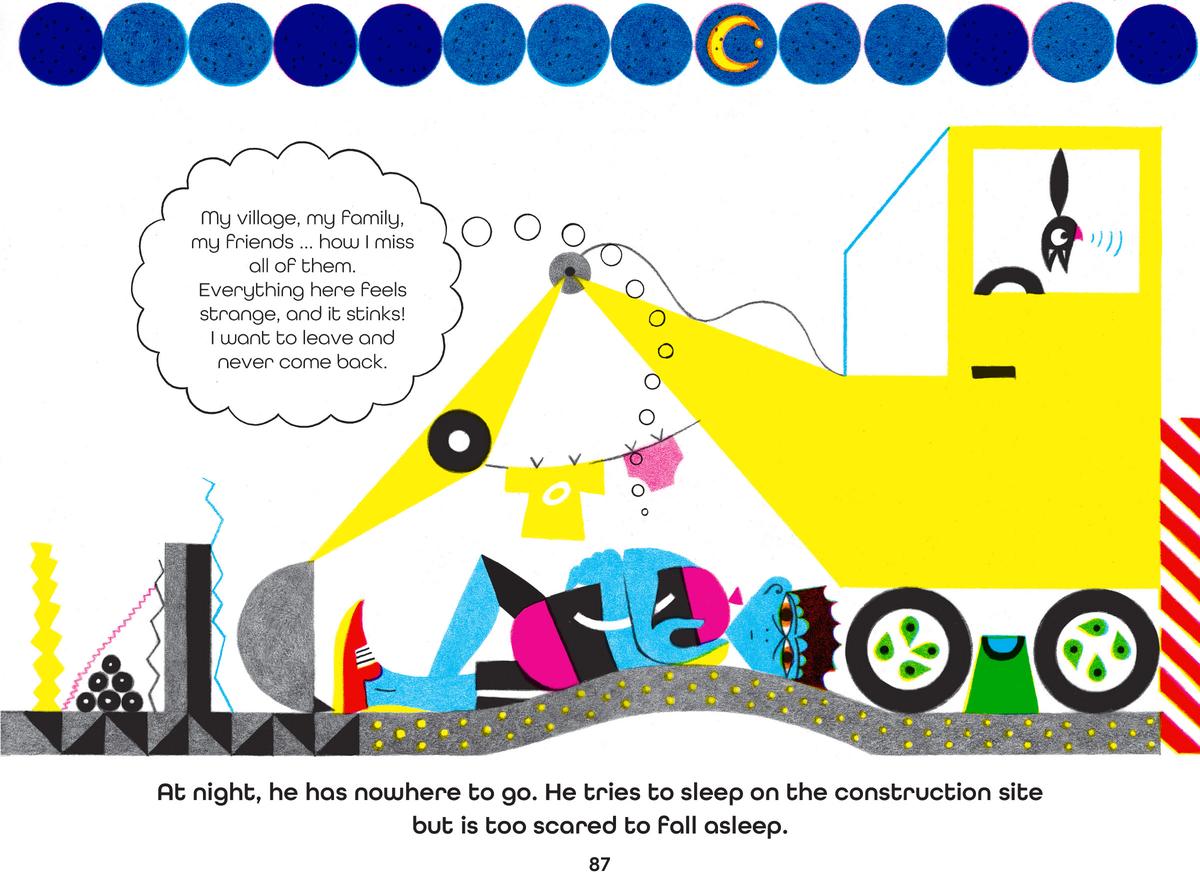

In ten loosely connected stories, young readers meet Nilou, Tsongai, Imai, Afia, Bibir and a number of other characters as they navigate their daily lives and look for ways to overcome problems such as food shortages, climate change, deforestation and underfunded schools. They are compilations based on the lives and experiences of people from all over the world. Duflo says it was important to her that the stories were not tied to any particular place, culture, religion or race, and so they are set in a nameless, imaginary village with no cultural and geographical markers.

The characters are depicted by Olivier in a stunning variety of skin tones: from yellow to green to blue. The illustrations are full of bold shapes and colors. The trees are striped, the ground is full of patterns and often curved. “I took the S-curve from the bad economy and turned it into a beautiful and meaningful element (the ground) that evokes the ups and downs in the stories and lives of the characters,” Olivier explains. The S-curve, I found out through further research, represents the relationship between a person’s current and future income based on the investments they can make in their health, education and general well-being.

Cheyenne Olivier | Photo credit: Sébastien Hubner

“Young people are part of the solution”

Was it difficult to transform decades of work into stories for children? Duflo admits that it is much more difficult to write for children than for adults, but “I knew what needed to be addressed on each topic and the idea for some stories, like Nilou’s, had been in my head for a long time.”

Nilou Skips School tells the story of a young girl who is struggling with her schoolwork and is skipping school. Her underpaid teacher struggles to help the students, but a social worker trains the older children of the village to teach Nilou and her friends.

A page from Nilou skips school

The stories are not didactic and are free of clumsy platitudes. Instead, dialogue and a concise narrative style are used to move the story forward. An essay at the end of each story explains the underlying concept, making the books accessible to a wider group of children. “Younger children can have an adult read the stories to them and leave it at that, while older children can read the story themselves with the accompanying essay,” says Duflo.

So what does she want readers to take away from the stories? “In children’s literature, the child is too often either an innocent victim or responsible for saving the whole world,” she answers. “We wanted to make it clear that young people are part of the solution. There are things you can do, but you are never alone. You are part of a society.”

This is clearly expressed in stories like “Thumpa in the Shade of the Trees”, based on the Chipko movement. When the personal story of a village elder inspires a child to save trees from being cut down by loggers, he follows his example. And soon the other children and then the adults join in.

A page from Thumpa in the shade of the trees

Creating empathy

The authors are aware that an English-language children’s book in India is likely to reach readers who are far more privileged and wealthy than the characters in the book. “Even though readers of the book may not have had similar experiences, we hope that the stories will make them realize that these children are not so different from them,” says Duflo.

And maybe that’s why the young reader I met at the book club should read these stories. He should understand that Nilou, Afia and Neso are not so different from him, that they have just as much right to a life of dignity and quality as he does. That understanding and empathy is perhaps the first step towards bridging the gap between them.

This is a premium article available exclusively to our subscribers. You can read over 250 such premium articles every month.

You have reached your limit for free articles. Please support quality journalism.

You have reached your limit for free articles. Please support quality journalism.

You have read {{data.cm.views}} out of {{data.cm.maxViews}} free articles.

This is your last free item.