The case for coding automated vehicles with human values – Monash Lens

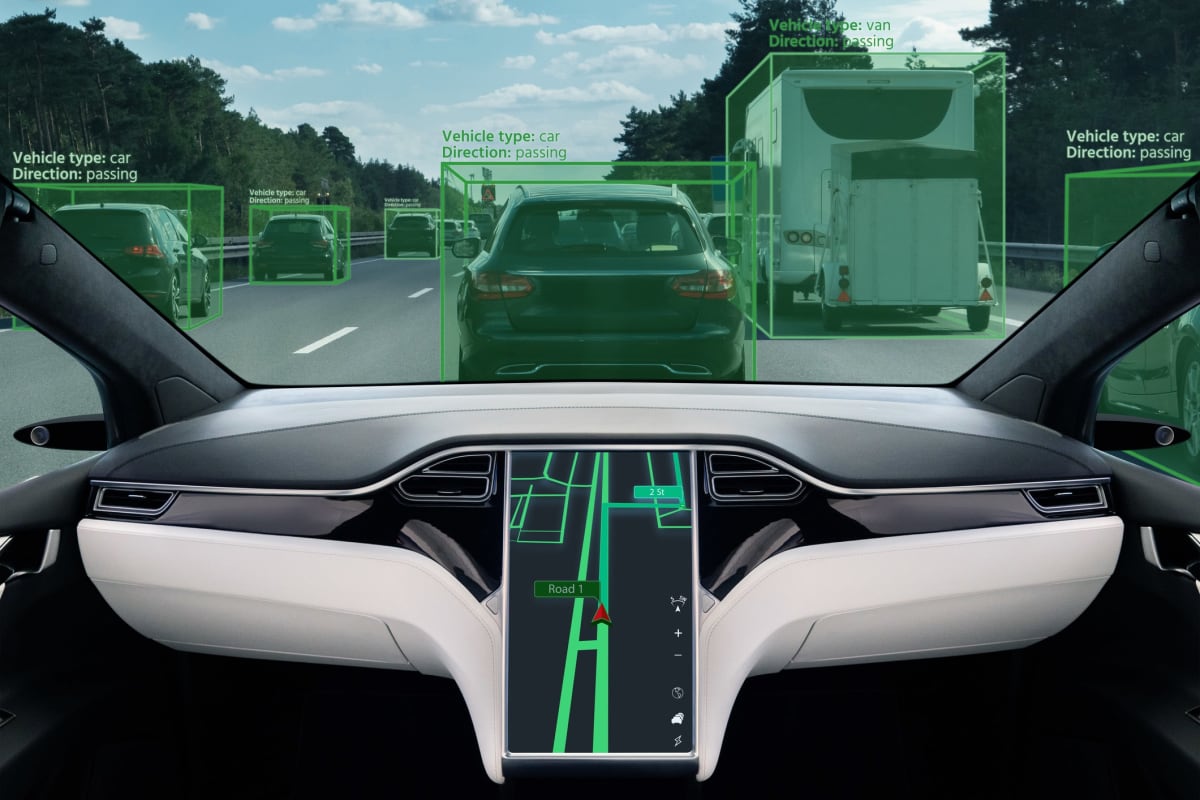

While fully self-driving cars are a hypothetical product of the future, some levels of autonomous vehicles (AVs) already exist.

As with other forms of AI, people must weigh the costs and benefits of integrating this new technology into their lives.

On the other hand, autonomous vehicles could promote sustainable transport by reducing congestion and fossil fuel consumption, increasing road safety, and providing accessible transportation options to underserved communities, including those without a driver’s license.

Despite these advantages, many people are hesitant to use fully automated autonomous vehicles.

In an Australian study led by Sjaan Koppel of Monash University, 42 percent of participants said they would “never” use a self-driving vehicle to transport their unaccompanied children, while only 7 percent said they would “definitely” use one.

Our distrust of artificial intelligence seems to stem from the fear that the machine will take control and make mistakes or decisions that are inconsistent with human values, as depicted in the 1983 adaptation of Stephen King’s horror film about the murderous car Christine. We fear being increasingly excluded from the machines’ actions.

Trust and technology

Six different AV levels are described, with level zero offering “no automation” and level five offering “full driving automation,” with humans defined only as “passengers.”

Currently, levels 0 to 2 are available to consumers, while level 3 – “conditional automation” – is commercially available on a limited basis. The second highest level of automation, level 4 or “high automation”, is currently being tested.

The autonomous vehicles available to consumers today require drivers to monitor the automation and override it when necessary.

To ensure that autonomous vehicles don’t become Christine and take on a life of their own, AI programmers use a process called “value alignment.” This alignment will become especially important as more autonomous vehicles are developed and tested.

Value alignment is achieved by programming the AI – either explicitly in the case of knowledge-based systems or implicitly through “learning” in neural networks – so that the behavior corresponds to human goals.

For autonomous vehicles, the orientation would vary somewhat depending on the vehicle’s intended use and location, but would likely take into account cultural values (e.g. stopping for an ambulance) in addition to local laws and regulations.

The “trolley problem”

AV alignment is not a simple task. AV alignment becomes complicated when the vehicles encounter a real-world challenge, such as the “trolley problem”.

The trolley problem, first attributed to philosopher Philippa Foot in 1967, makes us think about human morality and ethics. Adapted to AVs, the trolley problem can help us consider the extent to which AV alignment is possible.

Imagine this scenario: A fully automated autonomous vehicle is heading towards an accident and must react. It can swerve to the right to avoid five people, but hit one person, or it can swerve to the left to avoid one person, but put all five at risk.

What actions should the AV take? Which option is most consistent with human values?

Now imagine this scenario: What if the vehicle was a level one or two autonomous vehicle where the driver remained in control – which direction would you steer when the autonomous vehicle’s “warning” sounds?

What if you had the choice between five adults and one child?

What if that one person was your mother or your father?

You may be relieved to know that there should never be a “right” answer to the trolley problem.

Read more: Your self-driving car won’t kill you – as long as research also takes people and society into account

This problem highlights that aligning AVs with human values is not so easy.

Consider Google’s mishap with Gemini. An attempt at alignment – in this case, reducing racism and gender stereotypes by programming the large language model – resulted in misinformation and absurdities (e.g. Nazi-era soldiers were portrayed as people of color).

Finding consensus is not easy, and even deciding whose values and goals to align with remains a challenge.

However, the ability to ensure that autonomous vehicles are consistent with human values also has its advantages.

Balanced autonomous vehicles could make driving safer, as in reality, people tend to overestimate their own driving skills. Most accidents are due to human errors such as speeding, distraction or fatigue.

Could autonomous vehicles instead help us make our driving safer and more reliable? After all, technologies like lane departure warning and adaptive cruise control already help us be safer drivers in Level 1 autonomous vehicles.

Human orientation… for humans or AI?

As the presence of these vehicles on our roads increases, it becomes increasingly important to encourage people to use autonomous vehicles responsibly.

Our ability to make effective decisions and drive safely in conjunction with AV technology is of utmost importance.

Worryingly, research shows that people tend to rely too heavily on automated systems like AVs, and this bias against automation is a hard habit to break. We tend to view technology as infallible.

“Death by GPS” is a common phrase today because we tend to blindly follow navigation systems – even when there is irrefutable evidence that the technology is wrong. (You may remember the case of the tourists who drove into a bay in Queensland after trying to “drive” to North Stradbroke Island.)

The AV trolley problem shows that technology can be just as fallible as humans (perhaps even more fallible because of their disembodied perception of the world), but perhaps for different reasons.

Read more: Will self-driving cars solve the problem of traffic congestion?

The dystopian scenario where AI takes control may not be as dramatic as we are led to believe. A bigger threat to AV safety may be a silent but very real willingness among humans to simply hand over control to AI.

Our uncritical use of AI influences our thinking, and our senses become dulled, including our sense of direction. All of this means that our driving skills are likely to suffer as we become more complacent with technology.

While there may be Level 5 autonomous vehicles in the future, the present still relies on human decisions and our very human capacity for skepticism.

Exposing drivers to autonomous vehicle failures can counteract automation bias. Combined with demands for greater transparency in AI systems’ decision-making processes, autonomous vehicles may be able to increase or even improve human-driven road safety.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.