What 3 famous thinkers said about the meaning of life

“What is the meaning of life?” is simultaneously one of the oldest questions in philosophy and a relatively new concept: While the search for meaning goes back further than the ancient Greek thinkers, Arthur Schopenhauer only really began to ask the question in the middle of the 19th century. the sense of life (“the meaning of life” in his native German). He concluded that it is the “will to live” or instinctive striving, and that peace comes from the eradication of this will. Many thinkers have addressed the question of the meaning of life for different purposes, and their work can help us grapple with the same problem ourselves – although their conclusions are rarely clear-cut.

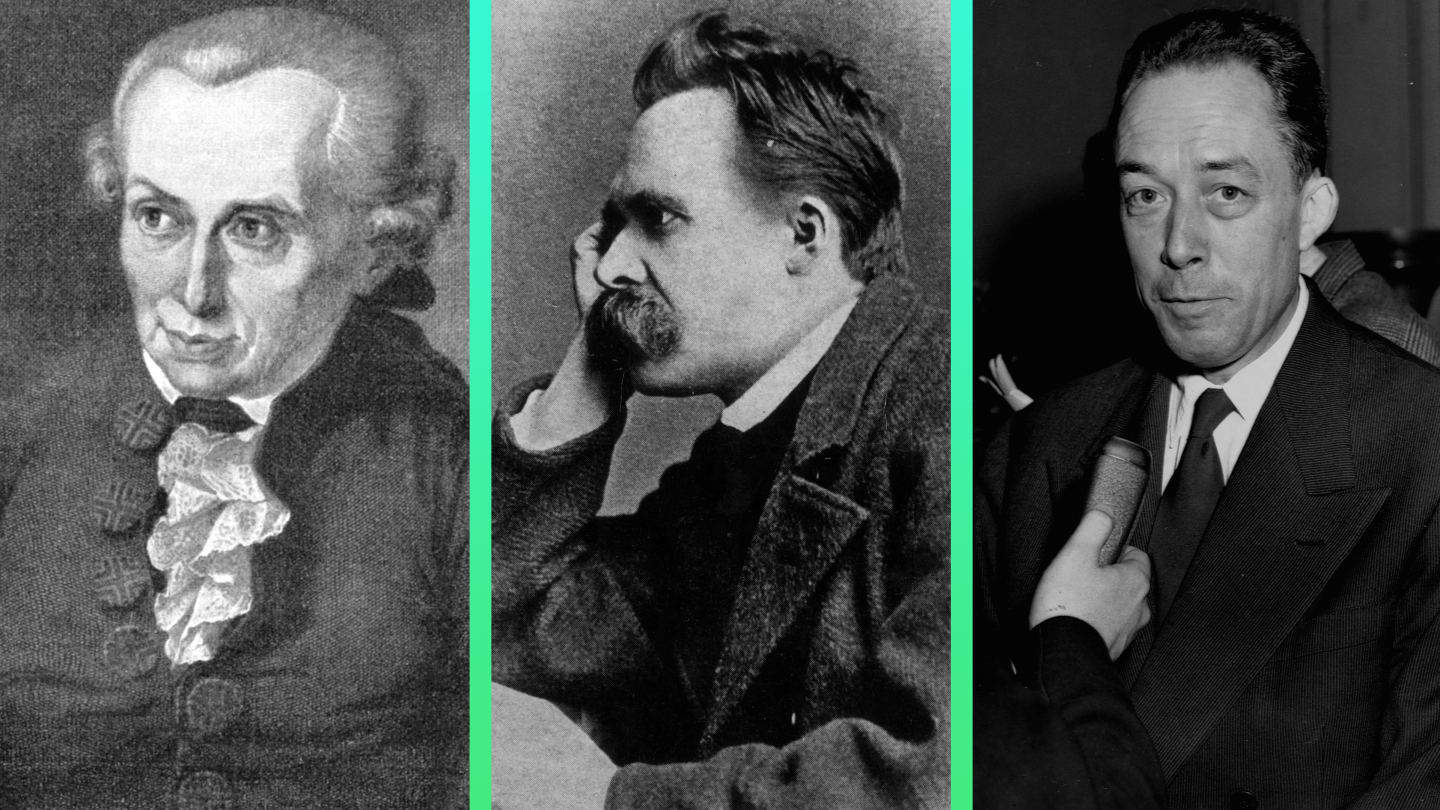

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) earned the title of “Father of Modern Ethics” despite leading a life widely regarded as exceptionally boring. So boring that, according to legend, his neighbors claimed they could set their clocks by his daily walk.

Because his work predates Schopenhauer’s, Kant did not specifically address the question “What is the meaning of life?”, but his work addressed the issue directly and is so fundamental that it is worth studying. Kant would probably have answered in one of two ways.

Kant wanted to create a moral system that would allow a person to derive the content of his moral actions (what should be done in a particular individual case) from the definition of morality (the very essence of the word). should). He believed that this would enable us to formulate a morality based entirely on rationality, which in turn would enable us to formulate synthetic a priori Knowledge – knowledge gained purely from reason, as opposed to experience, which tells us something previously unknown about the world – about the moral value of our actions. The result is his “categorical imperative”, which he defines in his Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals:

“I should never act otherwise than that I could will that my maxim should become a universal law.”

In Kant’s view, an action can only be considered acceptable if the motivating principle or maxim underlying it can be applied universally and without contradiction. The classic example is lying: if everyone lied, no one would believe anyone, and it would be impossible to lie. This only tells us what not to do, but has profound implications: if we look closely enough at ourselves and the world we live in, we can derive objective standards for our lives.

Kant’s second possible answer can be found in his Critique of Pure Reasonin which he attempted to respond to ideas of the Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711-1776). Kant outlined what he believed to be the conditions under which experience is possible and argued that all knowledge is the result of a dual process: “Intuition and concepts therefore constitute the elements of all our knowledge, so that neither concepts without an intuition corresponding to them in some way, nor intuition without concepts, can produce knowledge. Both are either pure or empirical.” In other words, thinking is a combination of sense data that we gain through what Kant called our “intuition” and interpretive frameworks called “concepts.”

But Kant did not believe that we could receive all our sense data or our concepts unfiltered. He believed that there was a priori Forms of these abilities that have shaped our experience of the world – and this form of concepts is cause and effect.

So when Kant said, “The pure or general laws of nature, which, without being based on any particular perceptions, contain only the conditions of their necessary union in experience,” he was arguing that general laws (such as cause and effect) are actually the product of our minds and enable us to have intelligible experiences. According to this argument, cause and effect (and space and time) do not necessarily exist outside of our minds. The implication is that life, an effect, may have no meaning, no cause, outside of the processes of our minds.

Kant reconciles these views with the ultimate philosophical way out – turning to God. However, these strands are taken up and expanded upon by other great thinkers.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) is one of our most misunderstood philosophers, due to the way his sister and executor, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, distorted his works after his death. According to Britannica, she “edited them without scruples or understanding” and “attained a wide audience with her misinterpretations.” Nevertheless, he was a deeply troubled thinker whose work would influence millions of people.

Nietzsche rejected Schopenhauer’s idea that all life is driven by a “will to live,” noting that some beings die for their goals. Instead, he proposed a “will to power,” in which living beings want to “act out” their power (in other words, affirm and realize their unique individual potential).

But what is our individual strength? Nietzsche rejected Kant’s preference for pure reason and instead turned to psychology to solve the problem: “For psychology is once again the way to the fundamental problems,” he wrote in Beyond Good and Evil. According to Nietzsche, one must abandon social, religious and historical expectations to become a “free spirit” or someone who thinks for himself (a philosopher). Only then can one progress “beyond good and evil” or the morality that the world imposes on us. Instead, he writes, we must search for what “lies at the bottom of our soul, right at the bottom, something unteachable, a granite of spiritual destiny, predetermined decision and answer to predetermined, chosen questions. In every cardinal problem speaks an unchanging ‘I am this’; a thinker cannot learn anew about man and woman, for example, but only learn completely – he can only follow to the end what is ‘fixed’ in himself about them.”

In Nietzsche’s view, with enough psychological introspection (although he notes that this alone may not always be sufficient or entirely accurate), we can find our own unique purpose – buried beneath the layers of society and convention – which we should then seek to realize at all costs.

Albert Camus (1913-1960) was a French-Algerian philosopher, author of The strangerand a leading thinker of the group associated with the philosophical movement of existentialism (although Camus rejected this connection and his position with respect to the movement remains the subject of lively debate). His ideas on the meaning of life can be seen as successors to Kant’s second possible conclusion. Camus recognized that it is human nature to look for a cause when seeing an effect. He also accepted as a premise that all previous attempts to find an objective “meaning” of life had failed. Existentialist philosophers call this gap – between our need for an explanation and the inherent lack of one in reality – “the absurd.”

Camus compared human existence in the face of absurdity to the Greek myth of Sisyphus, a man punished by the gods by rolling a stone up a hill for all eternity… only to have it roll back down just before reaching its destination. Camus’ response to this situation is to defy reality in no uncertain terms. As he wrote in his essay “The Myth of Sisyphus,” “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” By realizing that meaning is there to be created, not given, we actually gain the ability to see things as meaningful—and are better off for it.

Read more articles on philosophy: