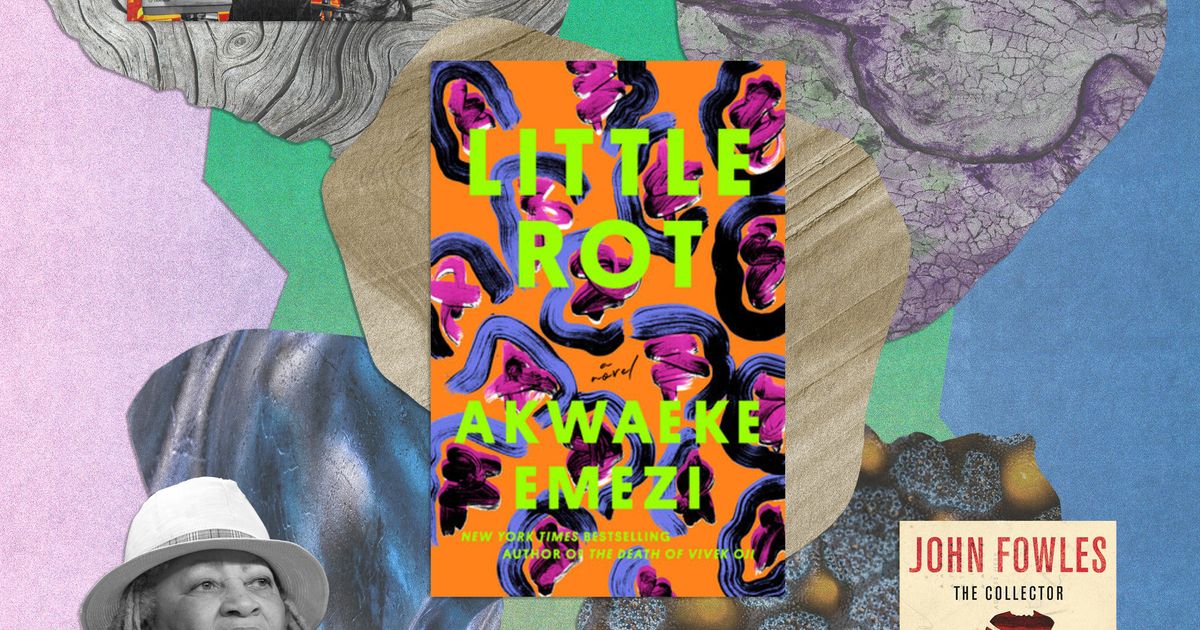

There is no hiding place in “Little Rot” by Akwaeke Emezi

Photo illustration: by The Cut; Photos: Retailer, Getty Images, Universal Pictures

Small rot — Akwaeke Emezi’s eighth book since her debut in 2018, Fresh water — forces us to see the world with painfully sharp clarity. As relevant as it feels to this particular moment, when the attention economy makes it easy to obscure reality in favor of blurry but attractive superficial satisfactions, the novel has been in the works for ten years, rooted in a short story Emezi published in 2014. Back then, the author was a frequent visitor to Lagos, the distant “big city” of his youth, while growing up in the smaller city of Aba, Nigeria. “When I actually started spending time there, I became aware, in a very naked way, of what a violent city it was,” says Emezi. “The violence wasn’t contrived. Nobody tried to hide it. Nobody tried to pretend it was better than it was, and, what was even more terrifying, it was so normalized.”

In recent months, social media has also given those who want to see it a digital window into the enormous scale and soul-destroying severity of the violence faced by so many people in Palestine, Sudan and Congo. For Emezi, it is triggering but not shocking. “There was been “There are multiple genocides going on,” they say. Both parents survived genocides, and Emezi still struggles with complex post-traumatic stress disorder from a childhood in which they were regularly exposed to violent sights, smells and sounds. “I know certain things that I would rather not know, and I’ve written about them before – I know the smell of bodies that have been in the sun too long, and all that. Those are core memories that I have.”

It is precisely their intimate knowledge of violence that has given them a pragmatic perspective on what can be done about it. “Feelings about violence are such a personal thing. What is important to me is the plot,” says Emezi. They see their work as storytellers as their role in the collective struggle for liberation, with the philosophy that no one can do everything; each individual must find their niche. In their previous novels, including domestic animal And You fooled death with your beautythe identities of their protagonists are not the source of their primary conflicts or challenges. This is especially true for Small rotbut Emezi does something different. They were fascinated by the everyday nature of evil, by how a person’s morals can falter or change depending on the environment. “It doesn’t give you hope for a better future, but it does something else that is very important in a story, which is to teach you how to look at things,” they say. “We can’t leave this world, let alone start building a new one, if we aren’t able to see the truth about what this world is.”

My book was based on life, not necessarily on other media. I worked with a friend on adaptations. Afterward, they said, “I just treated it like it was a feature film.” And we was I work on it as if it were a movie. When I have a story, I see it in my head first. So when I write a book, it’s a transcription. There’s a movie playing in my head. Small rot feels very much like a fast-paced dark thriller. It has this frenetic energy. Dev Patel’s Monkey Man has a similar mood as John Wick. It is a certain kind of city that does not exist in the West. It has a different atmosphere, being chased through this tropical, overpopulated city. That is something Monkey Man and this book really have something in common. There’s all this structural corruption – all these people who have immense power, and no matter where you go, they can get to you. The problem with cities like these, where power is structured like that, is that the people at the bottom are desperate because the people at the top have stolen everything from them, and people will attack you for any shred of power or resources. Monkey Manfor secureis written in this line. And it is bloody too. Small rot isn’t particularly gory, but I think it’s emotionally gory. It has this brutality.

The Nigerian music scene is amazing and much bigger than Afrobeats, the pop version of everything. But there are all these other artists, like Obongjayar and Lady Donli and Kah-Lo and the Cavemen. These are some of the artists that made the soundtrack of Small rot. There’s a song by Lady Donli called “Cash.” It’s a great song and in my head it’s the soundtrack of the character Ola. The chorus goes, “I’m addicted to money.” She’s got her priorities right and that works to her advantage. She’s actually the only person who just floats through all of this because she’s like: I understand it. I have decided what role I play in it. I can exercise power and influence here and there. I know what to look out for. I know what not to look out for. She’s got it.

With Toni Morrison, it’s never really about a specific book. It’s always about her writing style, because that’s what influenced the way I write the most. When I was a beginner, I was a sucker for flowery prose. That’s how I wrote. Every single sentence was stuffed with a thousand metaphors. I briefly went to an MFA program, and they teach a very different writing aesthetic, which is “a sentence as clean as a bone.” I didn’t like that either. Morrison was an example to me of a writer who could write a beautiful sentence that was still clean and precise. That’s not really taught with that level of commitment in an MFA program. They teach a very economical “cut all the stuff out,” which to me is a very white way of writing. It’s like taking all the spice out. It’s a different way of writing. With Morrison, it was like you can write lushly, you can paint all these great pictures, but the technique is still strict.

When I cite my authors, it’s always Toni Morrison and Helen Oyeyemi, because Helen is a fantastic but incredibly strange writer. I read Helen’s books when I was a baby, and as an immigrant in America, I was able to write what I wanted and experiment with my writing in a very special way. I feel like a lot of authors of color don’t necessarily take the freedom to experiment with such a wide range of book types or structures. Helen Oyeyemi is someone who really experiments and ends up writing such beautiful, strange books.

The collector is written from two perspectives. Half the book is written from the perspective of the kidnapped person, the other half from the perspective of the kidnapper. Someone recommended it to me and I read it years ago, but I really liked that he presented the perspective of the kidnapper. It has a choice of perspectives and an interest in rot, in corruption. I had a friend who read it. Hogg, by Samuel Delany, and we talked about it a lot, but I didn’t read it because I honestly didn’t think I could handle it. I was really curious, What would it look like if I let my imagination run wild and wrote down whatever evil comes to mind? I have never written such a book. But Small rot is as close as I can get. My imagination could write a really evil book, but that wouldn’t be consistent with my actual principles. I don’t judge any other author. But I don’t think I could go much deeper and still be OK. I’d rather be OK.

See everything