In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine 1900-1930s, Royal Academy

Now that Ukrainians are once again forced to fight for independence, it is time to reveal that many artists of the so-called Russian avant-garde actually originated from Ukraine. Famous pioneers of abstract art such as Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin, Alexandra Exter, Sonya Delaunay and Davyd Burliuk were born or grew up there.

And with Russian bombs raining down, it makes sense for security reasons to send your art treasures abroad. Most of the pieces on display at the Royal Academy therefore come from the National Art Museum and the Museum of Theatre, Music and Cinema of Ukraine, meaning the scope of the exhibition is limited to what they own.

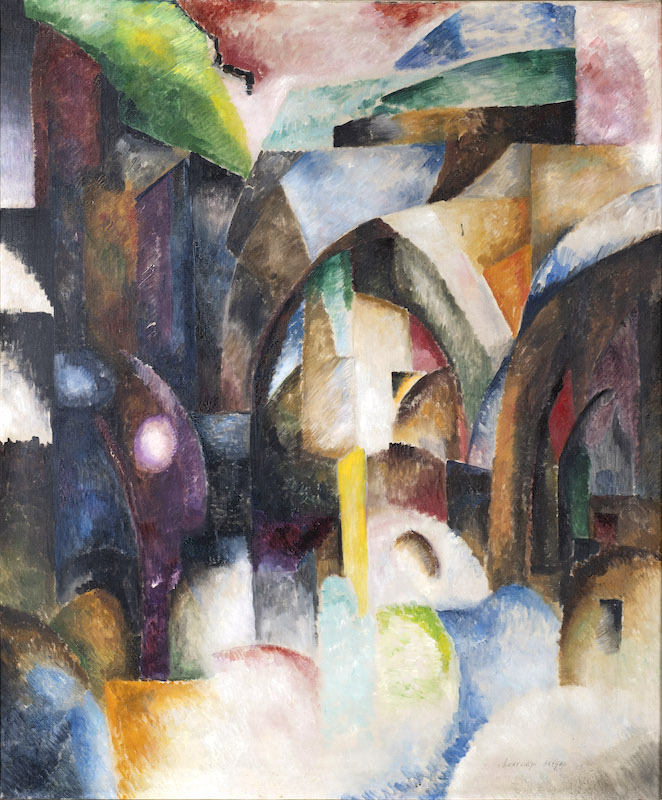

Exter was a powerhouse of creativity as a painter and theatre designer (Picture right: Composition (Genoa)1912). Born in what is now Poland, she grew up in Kiev, where she studied art before moving to Paris in 1907. She met Picasso and Braque, exhibited there, and became a major figure in the art scene. Over the next few years, she jet-set between Paris, Rome, Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and Kiev. She was particularly interested in Ukrainian folk art, and in 1915 she founded craft cooperatives in the villages of Skoptsi and Verbivka. In 1918, she founded a private art school in Kiev, teaching painting and theater design. This gave rise to the generation that shaped Kiev’s radical theater scene.

Exter was a powerhouse of creativity as a painter and theatre designer (Picture right: Composition (Genoa)1912). Born in what is now Poland, she grew up in Kiev, where she studied art before moving to Paris in 1907. She met Picasso and Braque, exhibited there, and became a major figure in the art scene. Over the next few years, she jet-set between Paris, Rome, Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and Kiev. She was particularly interested in Ukrainian folk art, and in 1915 she founded craft cooperatives in the villages of Skoptsi and Verbivka. In 1918, she founded a private art school in Kiev, teaching painting and theater design. This gave rise to the generation that shaped Kiev’s radical theater scene.

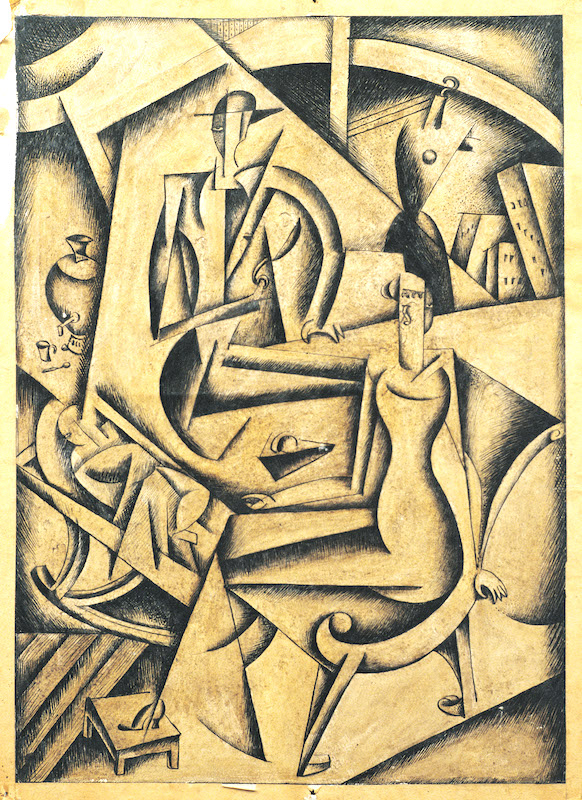

On display are three of her early cubo-futurist paintings as well as costume and stage designs by herself and students such as Anatol Petrytskyi, a painter and brilliant theater designer. (Picture bottom left: The tailor’s family, C. 1920 by Marko Epshtein).

Delaunay was born in Ukraine but grew up in St. Petersburg. In 1905 she moved to Paris, where she became an influential figure in the art and design world and married Robert Delaunay. She remained there until her death in 1979, when her importance was finally recognized. One of her wonderfully colorful abstract paintings is shown.

There is no mention of Tatlin, famous for his design of the Monument to the Third International, even though he lived and studied art in Kharkiv and from 1925 to 1927 was director of the theater, film and photography department at the Kyiv Art Institute, which became one of the leading art schools in the USSR under Soviet rule.

There is no mention of Tatlin, famous for his design of the Monument to the Third International, even though he lived and studied art in Kharkiv and from 1925 to 1927 was director of the theater, film and photography department at the Kyiv Art Institute, which became one of the leading art schools in the USSR under Soviet rule.

Malevich also taught at the institute from 1928 to 1930, at which time he abandoned Suprematism, the glorious form of abstraction that brought him an international reputation. Born in Kiev, he studied drawing there, but moved to Moscow in 1904, where he developed his radical abstraction. On display is a landscape in the rather wooden, figurative style he adopted after the Soviet authorities denounced abstract art as bourgeois irrelevance.

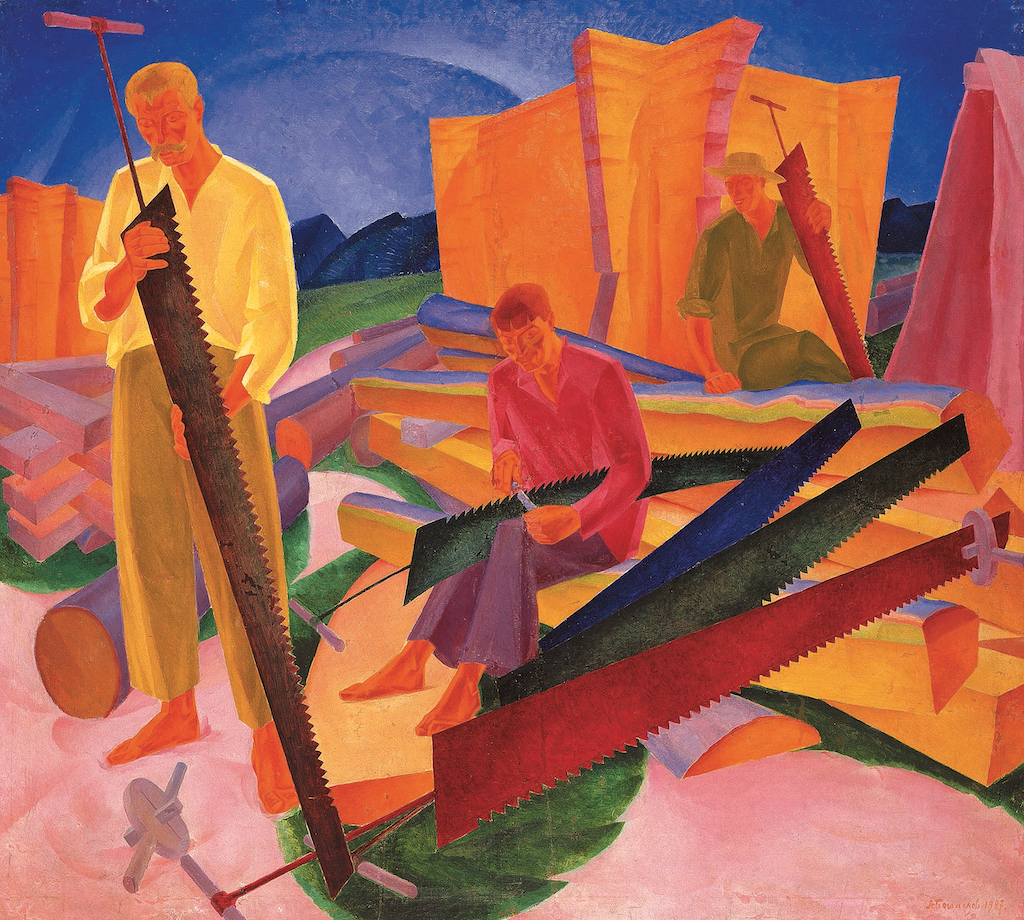

Despite his importance as a teacher and painter, Oleksandr Bohomazov (Main image) was only recently rescued from oblivion. From 1922 until his death in 1930, he was a professor at the Kiev Art Institute, where his theories of art, set out in his essay “The Art of Painting and the Elements,” became the standard course. Like Malevich, he softened the abstract elements of his Cubo-Futurist paintings to avoid censorship by the Soviet authorities.

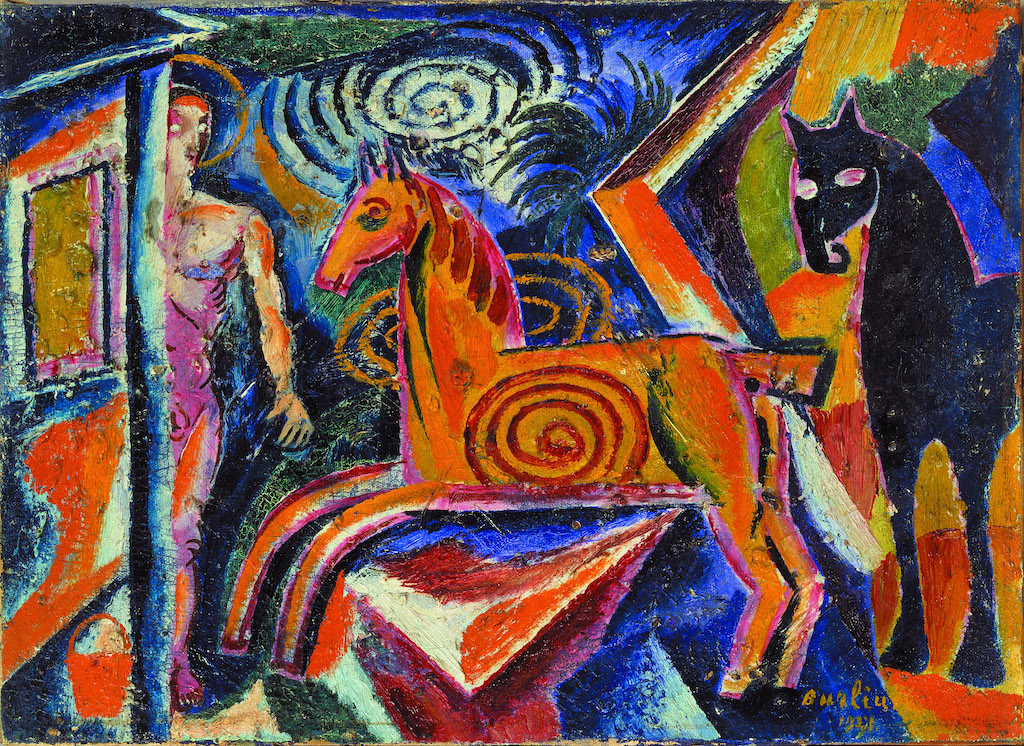

Their caution was right. In 1928 and 1930, the Russian pavilion at the Venice Biennale hosted a group of Ukrainian artists led by Mykhailo Boichuk, who created a fusion between folk art and geometric abstraction. Their recognition, however, was short-lived. Stalin denounced them as “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalists” and had them all killed or deported to labor camps along with the writers, designers and directors of the Kiev theater scene. Alexandra Exter had already defected to Paris and Davyd Burliuk to the USA. {Pictured below: carousel1921 by Davyd Burliuk). The exhibition ends with examples of the boring socialist realism that Stalin imposed as the official Soviet style. This modest exhibition is both a revelation and a disappointment. It whets the appetite for information on this fascinating subject, but with so few works by such significant figures on display, it does not even begin to do justice to their inspiring achievements. Nevertheless, it makes clear that Ukraine should be recognized as a cradle of modern art, alongside Paris, Rome, Moscow and St. Petersburg.

This modest exhibition is both a revelation and a disappointment. It whets the appetite for information on this fascinating subject, but with so few works by such significant figures on display, it does not even begin to do justice to their inspiring achievements. Nevertheless, it makes clear that Ukraine should be recognized as a cradle of modern art, alongside Paris, Rome, Moscow and St. Petersburg.