If I were only treated for PTSD, I might be dead

As a combat veteran who has deployed and fought in Iraq and Afghanistan, I know firsthand the long-term effects of war. The horrors of combat follow us home, haunt us at night, and cast shadows over our days. The weight of our experiences can be overwhelming, and for some, it is too much to bear.

Every day, 22 veterans make the heartbreaking decision to end their lives.

Many experts claim that our soldiers are dying from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). But in my personal and professional experience, PTSD is not the only cause of the veteran suicide epidemic; it is just one of several factors that lead veterans to that fatal, final decision.

To truly support our veterans and active duty soldiers, we must recognize that post-combat resilience is multifaceted. True treatment requires treating the whole person—mind, body, and spirit. A comprehensive program combines psychological, physical, cognitive, spiritual, and social care. We cannot isolate these components; they are interconnected, and each factor plays a critical role in promoting hope and healing.

Many kind-hearted and well-meaning ministries, organizations, and medical professionals focus on the wrong problem and therefore seek the wrong solution. Doctors try to treat PTSD with medication and talk therapy. While these options are useful tools, they are not necessarily the only or best solution.

I know this phenomenon because I experienced it.

In 2010, I returned home from the Korengal Valley in Afghanistan. Seven days of intense combat in one of the most dangerous places on earth changed me in ways I never imagined. I went into the field with rose-tinted glasses and returned with a distorted view of the world. I justified my actions by telling myself the killings were just – in the name of freedom, democracy and American values. And maybe that’s true, but there’s still blood on my hands.

Soldiers are trained to handle pressure and persevere on the battlefield. We endure the hardships and win the war. But the stress and trauma builds over the months and years of deployment. Warriors rarely break on the battlefield. We keep going. It is only when we try to return to civilian life that the effects of war emerge and our loved ones begin to suffer the effects that war has had on us.

After the first 10 years of my 20-year service, multiple deployments, and numerous conflicts and explosions, I suffered from traumatic brain injury and PTSD. The obsessions, anxiety, insomnia, and uncontrollable rage attacks were difficult to deal with. Even more, the headaches, chronic pain, blurred vision, mood swings, tinnitus, and memory loss felt like my brain was on fire, leaving me in a state of dark hopelessness. I was on the verge of losing my marriage and my career. I hated who I had become, and I despised my life. More than once, I wondered if it was even worth it.

I was sent to a doctor, given medication, and told to talk about it. But that didn’t help. When my treatment was changed to a more holistic approach that included cognitive therapy to treat my concussion and Christian counseling to deal with my existential crisis, my healing process began.

If I had only been treated for my PTSD, I might be dead.

An estimated one in seven adults will suffer from PTSD at some point in their lives, with military personnel and veterans particularly affected. According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), PTSD is a serious illness that results from experiencing or witnessing traumatic events. Veterans are particularly vulnerable to the disorder due to deployments to war zones, training accidents, and sexual trauma in the military.

Research shows that the risk of PTSD increases during deployment. Some studies find that deployed veterans are three times more likely to develop PTSD than non-deployed veterans.

Since 2011, over 2.8 million men and women have deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan to fight terrorism. The scars of war run deep, affecting not only our psychological well-being but also our physical, cognitive, social and spiritual health. When we return to civilian life, many of us feel lost, disconnected and purposeless.

Feelings of grief and guilt increase, stress levels rise and lead to insomnia. Chronic pain leads to opioid addiction. Destructive lifestyle habits develop, such as poor nutrition, substance abuse and reduced physical activity.

When someone experiences trauma, it affects them on multiple levels. Psychologically, PTSD can lead to more pronounced cognitive dysfunction, often manifesting as nightmares, flashbacks, and emotional turmoil. Cognitively, traumatic brain injuries impair memory and cognitive function. And spiritually, there is something even deeper—the moral injury.

Moral injury is a blunt trauma to the soul. Many symptoms require thorough understanding so that treatment can be properly guided and administered. Ideally, recognizing moral injury promotes resilience and is part of the holistic health model.

Together, we can honor the sacrifice of our nation’s warriors by ensuring they find peace beyond the battlefield, by building their resilience through effective treatment that focuses on the mind, body, and spirit. With this paradigm, we can stop the suicide epidemic and save our American heroes.

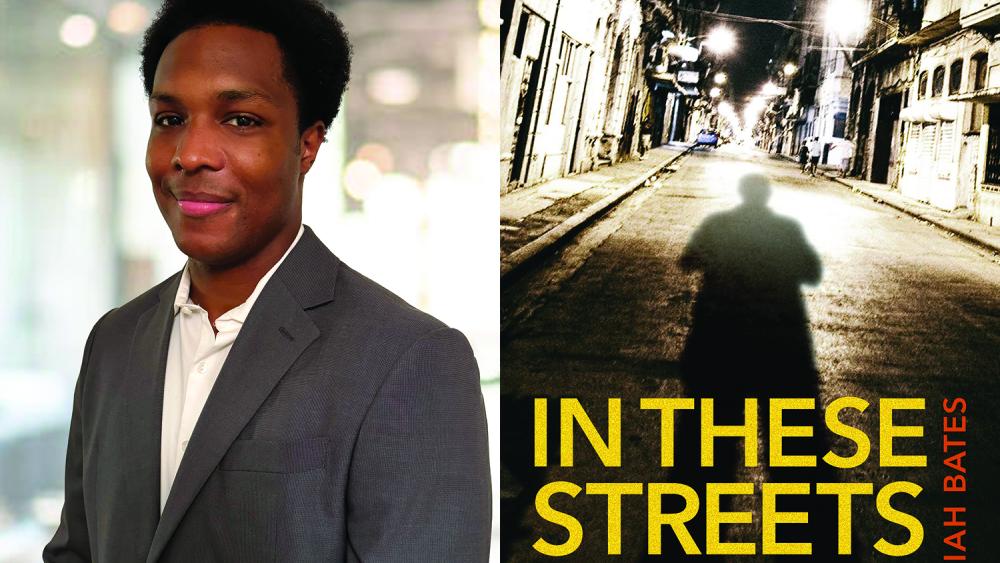

Dr. Damon Friedman, a decorated veteran of combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, retired from the Air Force as a lieutenant colonel in special operations. He is the founder of SOF Missions, which provides psychological, cognitive, physical, social and spiritual care to veterans.