Slotted headthe latest game from Silent Hill and Gravity Rush creator Keiichiro Toyama, who now runs his own studio Bokeh, is somehow even stranger than it looks. A chance revelation Ahead of Summer Game Fest, a game was revealed that involved jumping between bodies and battling fish- and insect-like skinwalkers while a paranormal mystery simmered in the background. Extensive hands-on time at the actual event revealed a game that had more action than expected, played better than the trailer suggested, and also felt refreshingly focused.

This wasn’t the smoothest or most satisfying action game I’ve played at SGF – this badge probably goes to Black Myth: Wukong – with some choppy animations and the camera disrupting the flow of the game. But mechanically, it’s solid enough to support the ideas that really make it stand out. Slitterhead doubles down on its central mechanic, body-swapping through possession, to a rare extent.

New body, who

You start out as a confused ghost who takes possession of a dog and follows scent trails in search of, well, anything. Soon you’re jumping quickly between the hapless citizens of Kowlong, a fictional 1990s Asian city, slowly fathoming what it means to be… whatever you are. I asked Toyama what kind of city he was imagining, and he said (through an interpreter) that he wanted to convey nostalgia for “chaotic” cities, places full of people and problems and flickering streetlights and colorful signs and dingy alleyways. “I’m impressed by how people go about their everyday lives in such an environment,” he says.

Possession is the answer to almost everything in Slitterhead. Can’t reach that ledge? Possess someone a few floors up. Need to get out of that building? Jump off, slow time just before you reach the ground, then jump into a new body before yours becomes a pancake on the concrete slab. You can also briefly hover outside your current host to sense nearby people, which has some implications for exploration. I’m told there are some non-human options, but even though you start as a dog, you’ll mostly be possessing people.

This also applies to combat, a third-person melee parry sandwich made of blood and bodies glued together. Possessing someone gives you a powerful damage boost for a few seconds, and you can immediately perform a gap-closing attack on your target, so you’ll want to keep switching. If your host dies, you’ll lose one of your three lives and get ever closer to the end of the game, so you’ll also want to jump off before a fatal attack hits. The crucial slow-motion escape opportunities this dynamic allows for are pretty entertaining. Of course, you want to have as many potential hosts around you as possible, so you can’t just let people die. You’ll want to soak up any blood nearby between jumps to heal yourself.

The idea is to win with numbers rather than brute force, though there are special, stronger characters that are more permanent additions to the story and better fighters that can sustain longer duels. These characters eventually form something of a loadout system that lets you choose who you take on most missions and what active or passive skills you equip. That’s right, folks: honest-to-goodness missions. There are some secret bosses and side quests, but Toyama, sitting on the sofa next to me during my demo, stressed that this is a fairly linear game. I couldn’t be happier to hear that. Not every game needs to be huge, and frankly, too many games are. Give me a dose of creativity that doesn’t last too long, and I’m on it.

Your melee attacks are appropriately weak at first for someone—or rather, something—trying to manipulate random old people, couriers, and wrong-wayers. Eventually, you’ll find a rhythm and be swinging bloody maces and swords with more oomph. Defense essentially boils down to a directional save system: hold down the block button, then at the last moment move the analog stick in the marked direction of an incoming attack. If you get it right, you can sneak a counter. I was never entirely comfortable with this system, having landed a zillion saves in about as many action games, but in a way that made me want to play Slitterhead more than put the game down in frustration.

Abilities like poison needles or group mind control attacks add some spice, but the key is to switch bodies, get a few free hits in while trying to attack from behind for extra damage, then switch again. Toyama says Slitterhead was partly inspired by his manga, and it makes me think of those scenes in action series like Hellsing where the fighters move faster than the eye can see, striking from multiple directions at once.

Less survival horror, but still terrifying

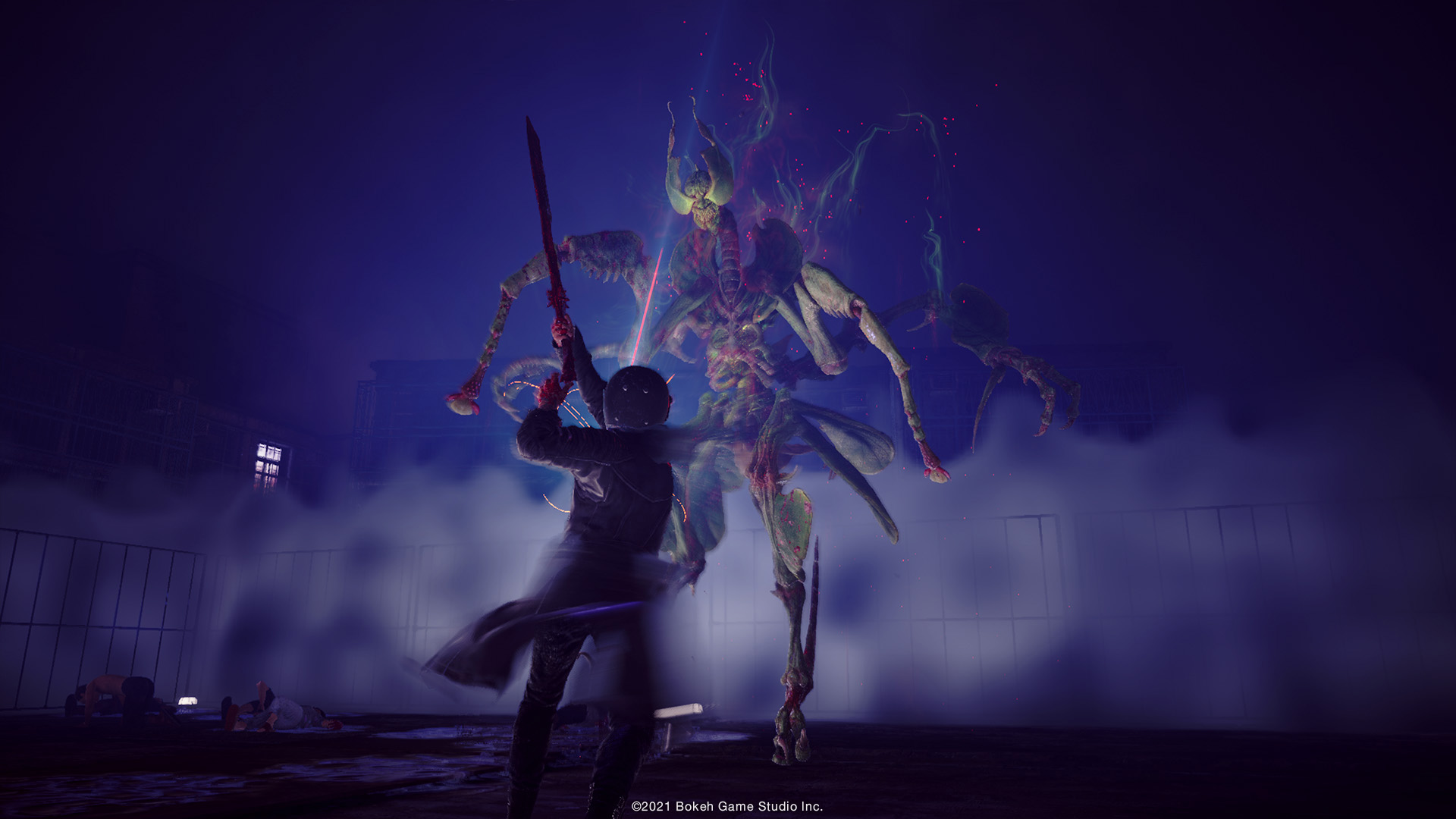

The titular Slitterheads occupy humans like you, but while you retain a fairly normal appearance and fight with weapons and skills forged from blood, these things conjure up some truly hideous figures. A woman runs towards you with a maggot nest for a head while a long, thin tongue slurps sickeningly to the ground. The limbs and head of a blue-ringed octopus burst forth from the ribcage of a poor citizen.

A boss I encountered in a later mission toward the end of my hour-long demo is what I can only describe as a praying mantis necromorph with a poor naked soul dangling from its torso. Bipedal lampreys—actually just two legs and a long neck barely supporting a toothy mouth—appear constantly, completely naked and all too proud with tiny, horrible butts. Needless to say, I immediately asked Keiichiro Toyama why these things have tiny, horrible butts. He laughed and said, “It was just a personal choice. Like Seinen manga, they’re not only terrifying, but they’re kind of funny in a way, you laugh at them.”

If you’re playing Slitterhead expecting to be scared to death, I think you’ll be disappointed. There’s a horror veneer here and some really disturbing creature designs, but the action is in the background and there’s an atmosphere of mystery that I find compelling in and of itself. Toyama explained that this is partly because survival horror games can have a smaller audience, and he wanted to make his style accessible to more players with this game.

The tighter nature of Slitterhead was partly due to the smaller budget and team, but Toyama sees this as an incentive rather than a problem. The result is an endearingly odd game that quickly made me a fan. The action is a little more chaotic than I’d like, but it’s the kind of crap I love, and so far Slitterhead feels like a straightforward, inventive action-horror game that knows exactly what it wants to be and pursues that odd idea with admirable focus.

–

Slitterhead will be released on November 8th for PS4, PS5, Xbox Series X and PC. If you are interested in everything the creator has worked on, From Snatcher to Silent Hill to Siren, be sure to check out the collected works of Keiichiro Toyama.