How I got there and why I never left” – Americana UK

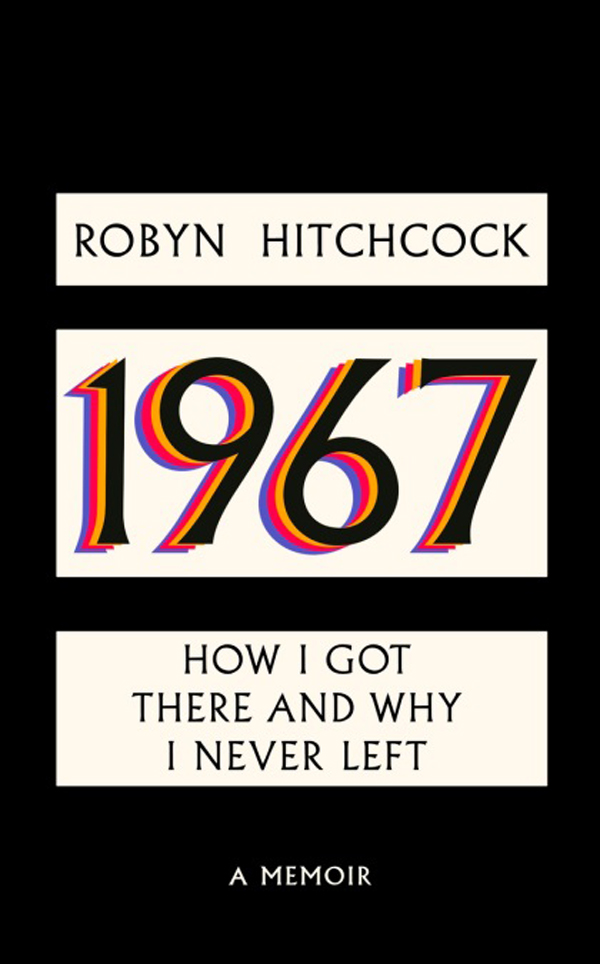

The year 1967 begins with 12-year-old Robyn Hitchock entering the English public school system, leaving behind his childhood home and his model trams and trolleybuses. He has had a relatively privileged life so far, shielded from the way most British children grow up, as he says here. He was educated privately at prep schools and passed the exams (including Ancient Greek) required for entry to Winchester College. This entertaining memoir chronicles his first two years there. His memories of the monochromatic routine of boarding school life are contrasted by his growing awareness of the Technicolor explosions of pop music in 1966-1967.

The year 1967 begins with 12-year-old Robyn Hitchock entering the English public school system, leaving behind his childhood home and his model trams and trolleybuses. He has had a relatively privileged life so far, shielded from the way most British children grow up, as he says here. He was educated privately at prep schools and passed the exams (including Ancient Greek) required for entry to Winchester College. This entertaining memoir chronicles his first two years there. His memories of the monochromatic routine of boarding school life are contrasted by his growing awareness of the Technicolor explosions of pop music in 1966-1967.

Amidst Hitchcock’s tales of the rituals and archaic rules of the Wykehamists (as the college’s students are called), he describes his listening progress based on records that he played on the “house gramophone” in his dorm. The Beatles “Rubber Soul” plays when he is first introduced to his dorm roommates, but it is his discovery of Dylan’s ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ which resonates with him completely: “The song seems to speak to me personally, stranded in this nest of aliens,” and when I heard the album “Highway 61 revisited” he is spellbound, especially fascinated by the eleven minutes and eighteen seconds of ‘‘Desolation Row’At his school, Hitchcock distinguishes between two groups of students: “the musclemen and the groovers.” He is destined to be one of the latter when he discovers Hendrix, Pink Floyd, The Incredible String Band and others. He buys the “The 5000 Ghosts or the Layers of the Onion” album because of its cover, and adds Mike Heron and Robin Williamson to his list of people who probably know the meaning of life (Dylan is at the top of the list). He even attends a “happening” where the music is provided by an art student from Winchester, a certain Brian Eno.

Aside from the memorable cast of characters (classmates, emotionally stunted teachers, and the janitor Mr. Trotter, whose job it is to wake the youngest student in each house, who must then wake his classmates) that populate the school, Hitchcock shares several memories of his family. His father, wounded in World War II, is distant and deals with his trauma through painting, his mother valiantly tries to curb his father’s slight eccentricities while fondly remembering his grandmother. Hitchcock’s fascination with crustaceans can perhaps be explained by his memory of collecting crayfish in the stream that runs beneath his family’s house.

Hitchcock skilfully brings to life the turning point that was, for the younger generation at least, 1967, when post-war Britain, with its slightly curly egg and cress sandwiches, took off on psychedelic wings. Like a hipper version of Anthony Buckeridge’s schoolboy hero Jennings, he deftly describes the slightly homoerotic undertones of boarding school life, while his descriptions of the records and musicians he discovers vividly capture the excitement and adventure of the music of the time. That he does this in his unique style, droll and with the occasional touch of whimsy and surrealism familiar to anyone who has ever seen him live, is the icing on the cake. It’s easy to imagine him telling these stories on stage between songs.

In his afterword, Hitchcock writes that for him “the year 1967 was over, but never ended.” He sees the publication of Dylan’s “John Wesley Harding” early the next year as a sign of the “great retreat” when psychedelia was declining in popularity. There is a brief mention of The Soft Boys, an opportunity for him to live out his boyhood dream, and he closes the book by saying that throughout his career he has carried the soul of 1967, a year that, he says, gave him a job for life. It’s a wonderful read.