Book review: “Corpses, Fools and Monsters” – The history and future of transsexual life in cinema

By Steve Erickson

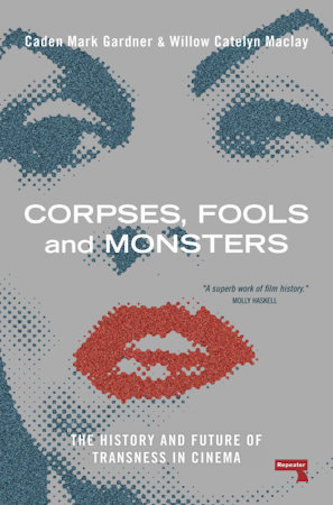

Corpses, fools and monsters: The history and future of transsexuality in cinema by Caden Mark Gardner and Willow Catelyn Maclay. Repeater Books, 332 pages, paperback, $19.95

Corpses, fools and monsters describes itself as a book about “the transsexual film image,” not about transsexual characters or filmmakers. It pursues an elusive goal, since transsexual people in cinema have until recently been defined almost exclusively from the outside: Gardner and Maclay devote a chapter to the performances of cis actors as transsexual characters. They write: “Transsexual cinema is not yet a full-fledged subgenre and has often been a collection of images, often recycled by non-transsexual filmmakers.” The book grew out of a frustrating exchange between Gardner and Maclay about 1999 Boys don’t cry in the couple’s “Body Talk” series. (You can read this eight-part dialogue between the authors Here.) In Corpses, fools and monsters the two authors combine their voices. Maclay’s essays and reviews, presented on her Patreon page, lean heavily toward autobiography, but the tone of Corpses, fools and monsters avoids the personal in favor of the analytical. The authors are modeled on Vito Russo’s popular gay film story The Celluloid Cabinet.

Corpses, fools and monsters describes itself as a book about “the transsexual film image,” not about transsexual characters or filmmakers. It pursues an elusive goal, since transsexual people in cinema have until recently been defined almost exclusively from the outside: Gardner and Maclay devote a chapter to the performances of cis actors as transsexual characters. They write: “Transsexual cinema is not yet a full-fledged subgenre and has often been a collection of images, often recycled by non-transsexual filmmakers.” The book grew out of a frustrating exchange between Gardner and Maclay about 1999 Boys don’t cry in the couple’s “Body Talk” series. (You can read this eight-part dialogue between the authors Here.) In Corpses, fools and monsters the two authors combine their voices. Maclay’s essays and reviews, presented on her Patreon page, lean heavily toward autobiography, but the tone of Corpses, fools and monsters avoids the personal in favor of the analytical. The authors are modeled on Vito Russo’s popular gay film story The Celluloid Cabinet.

The most common images of transgender people in the media were often made by those hostile to them, hence the three negative archetypes mentioned in the title. Even when cis filmmakers started with good intentions, their work reflected ignorance and unconscious bias, or made it easy to be co-opted by the truly hateful. (A few years ago, a transgender woman’s innocuous TikToks of her dancing went viral; some viewers decided they provided evidence that she was a serial killer, comparing her to The silence of the Lambs’ villain Buffalo Bill and the famous “Goodbye Horses” scene.) Gardner and Maclay’s criticism of Boys don’t cry reiterates the concerns the film’s critics have long had against it, but they go on to point out that the real damage is that it is the only relatively popular film to deal with transmasculinity. That means “the burden it has had to bear over the years has never been sustainable.”

Corpses, fools and monsters traces the beginning of the transgender film image to Christine Jorgensen, who became a celebrity in the early ’50s (although the pair examines some films made before her fame). She inspired Ed Wood’s Glen or Glenda and Gore Vidal’s novel Myra Breckenridge. Without going beyond the topic of film, Corpses, fools and monsters succeeds in touching on larger cultural and historical contexts. The chapter on 1970s cinema also addresses the negative reception of the memoirs of transsexual author Jan Morris. Puzzle; and the couple also quotes from Nora Ephron’s appalling review of Janice Raymond’s book The Transsexual Empirewhich popularized the topic of transphobic feminism.

Gardner and Maclay point to recurring narrative motifs, such as the revelation of a character’s transgender identity as a surprise twist. They argue that “this creates the assumption that a normative body is cisgender and everything outside of that realm is then subject to questioning, scrutiny and disposal.” Their 1991 interpretation The silence of the Lambs points out the flaws, but the pair respect the quality and complexity of director Jonathan Demme’s work: “Demme’s film wasn’t meant to be hateful, but audiences turned it into a vessel for misconceptions about transsexuality… But Gumb {aka Buffalo Bill} should never be seen as a joke. He should be seen as someone who is in pain and inflicting that pain on others.” Similarly, they give the 1992 film The Crying Game a fair assessment: “For all the good that The Crying Game does, he also stumbles, making for a complicated viewing experience of wins and losses.” The exploitative use of the reveal – Dil’s (Jaye Davidson) penis – as a marketing gimmick and then as a crude, offensive joke makes it difficult to appreciate the value of the rest of the film.

Jaye Davidson and Stephen Rea in The Crying Game. Photo: Searchlight Pictures

Of course, Lana and Lily Wachowski, the most famous transgender filmmakers in history, are the subject of a chapter. But the cisgender David Cronenberg film is given almost as much space, and that makes sense. The image of the transgender film is a recurring theme in the horror film genre, and in many ways, that presence has been extremely damaging. Psychoinspired by serial killer Ed Gein, launched a series of films linking gender nonconformity with murder. Dressed to kill went even further and dispensed with subtext by including television footage of Nancy Hunt, a real trans woman, and calling his villain, Robert Elliott, a transsexual. The mediocre slasher film Overnight camp would have been long forgotten – if it weren’t for the surprising ending. The protagonist, portrayed as a teenager, has a penis. A transcoded villain haunts this summer’s thriller hit Long legseven if these implications are much more subtle than before. Nevertheless, Maclay’s love of horror films is palpable in all her works: she celebrates the liberating possibilities it can offer for a radical reinterpretation of gender and sexuality. The use of metaphors from science fiction and body horror liberates films like shower And Under the skin, from the need to meet liberal demands to provide examples of “good representation.”

Surveys like this one usually focus on stereotypes in mainstream movies and television. (One example is the Netflix documentary Notice.) While this is an important critical work, it may be at odds with the fact that the media ignores independent films made far outside of Hollywood. To his credit, COrps, fools and mothers constructs an alternative canon that includes documentaries such as Dressed in blue, Southern Comfort, And The salt mines as well as the radical films of gay German director Rosa von Praunheim and Sadie Benning’s experimental Pixelvision video shorts. Gardner and Maclay’s groundbreaking investigation comes at an opportune time: in recent years, transgender directors have been making waves similar to the influence of New Queer Cinema in the early 1990s, with films like Jane Schoenbrun’s We all go to the World Exhibition And I saw the TV light upD. Smith Kokomo CityAlice Maio Mackay T-blockers, and Paul B. Preciados Orlando, a political biography. Yes, in some ways things are getting harder for transgender people, thanks to state repression and irresponsible behavior by the media and celebrities. But the last words of Corpses, fools and monsters give hope for the future: “Despite the compromised nature of the transgender film image of the past, many new horizons are possible for the transgender film image of the future, and this screen will tell our story in cinema with all of these images.”

Steve Erickson writes about film and music for Gay City News, Slant MagazineThe Scene in Nashville, Trouser pressand other media. He also produces electronic music under the name callinamagician. His latest album, Bells and whistleswas released in January 2024 and can be streamed here.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/6CEQ57JA36OQ5CTGCPJFU7F5NE.jpg)