Navy acquits black sailors of WWII ammunition explosion

WASHINGTON – The Secretary of the Navy announced July 17 the complete vindication of the remaining 256 defendants in the 1944 Port Chicago general and summary courts-martial. Carlos Del Toro, Secretary of the Navy, announced the vindications on the 80th anniversary of an explosion at the Port Chicago Naval Magazine in California, just inland from San Francisco, that killed 320 people, injured 400 others, destroyed two ships and a train, and damaged the nearby city of Port Chicago.

The 256 men were convicted at a court-martial of insubordination and mutiny when they refused to return to work without safety precautions after the explosion. Those convictions and the various sentences imposed have mostly been overturned or pardoned in recent decades, but the men’s families – the last of whom died in the 1990s – had lobbied for an official exoneration in which the Navy declared the men innocent.

This statement came on Wednesday.

“The Port Chicago 50 and the hundreds who stood with them may no longer be with us today, but their story lives on, a testament to the enduring power of courage and the unwavering pursuit of justice,” said Secretary Del Toro. “They are a beacon of hope, always reminding us that the fight for what is right can and will prevail, even in the face of overwhelming odds.”

An explosion and a rejection

The 256 black sailors were assigned to Port Chicago’s weapons battalions and worked as longshoremen, loading munitions and bombs onto ships to be sent overseas during World War II. A later Navy investigation found that security on Port Chicago’s piers and warehouses played a secondary role at best as black crews loaded increasing amounts of cargo under predominantly white officers.

On July 17, 1944, an explosion occurred in an ammunition ship. The cause of the explosion was never determined, but the shock wave ripped two cargo ships apart and leveled buildings for 300 meters in each direction in the river city of Port Chicago.

According to a Navy report on the explosion, shortly after 10 p.m., “there was a dull clang (possibly caused by a falling boom) and the sound of splintering wood, followed by a bright flash and a violent detonation on the pier, followed within seconds by smaller detonations and then the tremendous explosion of ammunition in EA BryanThe ship, most of the pier, all buildings within 300 meters and many of the flat cars collapsed. The explosion blew Quinault victory into large pieces that sank in the waters of Suisun Bay. A Coast Guard lightship was blown away from the ammunition pier and sank, taking its five-man crew with it. The 320 persons in the immediate vicinity of the explosions – naval personnel in the loading party, a Marine Corps sentry, the armed marine guard and the ship’s merchant marine crews, and civilian employees – were killed instantly. Of these, only the remains of 51 were later identifiable. Nearly two-thirds of those killed were African-American sailors.”

The 256 black men who survived the explosion were, unlike their white comrades, immediately put back to work in similarly dangerous conditions at a second Navy ammunition depot. When the black sailors refused to work without safety concerns, they faced court martial. Eventually, 206 returned to work, but all were thrown out of the Navy with fines and bad discharges. The last 50 who refused were charged with mutiny and given long prison sentences.

A final Navy investigation cleared the workers responsible of wrongdoing and instead concluded that the pier’s leadership and operational practices led to the disaster. Specifically, the investigation stated:

- By 1944, the Port Chicago Naval Magazine’s operating capacity was nearly exhausted due to wartime demands.

- Despite ongoing attempts to make up for the deficiencies, the training of officers and men in the handling of ammunition was at best inconsistent.

- Ever-increasing operational demands regularly led the command to override a number of basic safety procedures.

- At that time, U.S. Navy Board of Ordnance instructions did not adequately cover all aspects of security and weapons handling in ports during wartime. Due to the high tempo of operations, Port Chicago only selectively followed standard and more specific U.S. Coast Guard instructions from 1943.

In investigating the case, the Navy said Monday, the Navy’s general counsel concluded that “significant legal errors occurred in the courts-martial. The defendants were wrongly tried together despite competing interests and were denied meaningful legal representation. The courts-martial also occurred before the Navy’s investigative report on the Port Chicago explosion was completed, which would certainly have informed its defense and included nineteen substantive recommendations for improving ammunition loading practices.”

If family members of defendants in the 1944 Port Chicago General and Summary Courts-Martial would like to contact the U.S. Department of the Navy for future notifications on this matter or for additional information, please contact [email protected] or call 703-697-5342.

The latest on Task & Purpose

Related Posts

Manisha Koirala recalls a famous photographer reprimanding her when she refused to wear a bikini: “Jo mitti pighalne se sharmati ho…”

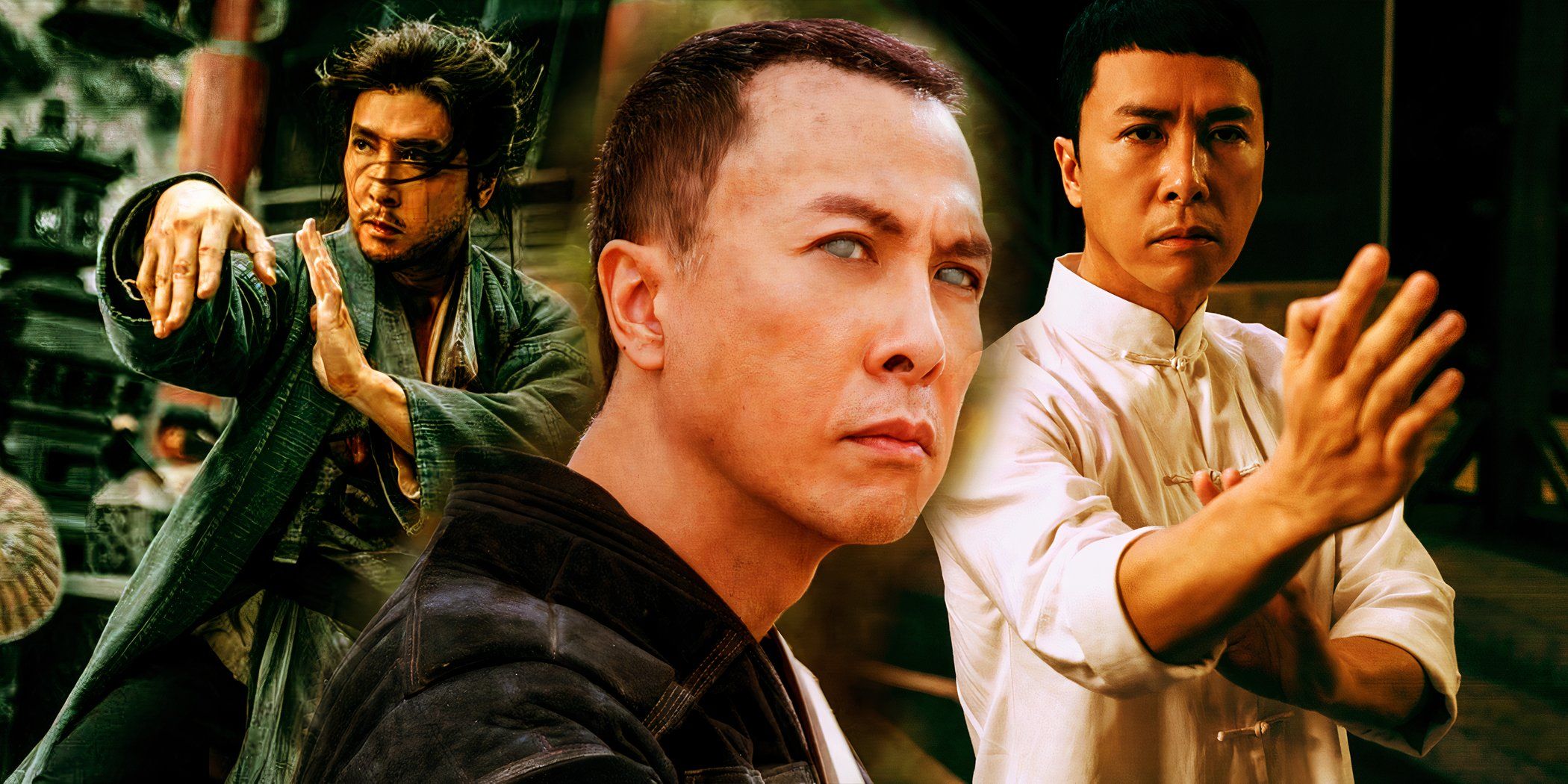

Every upcoming Donnie Yen action movie