Seven books to read if you have insomnia

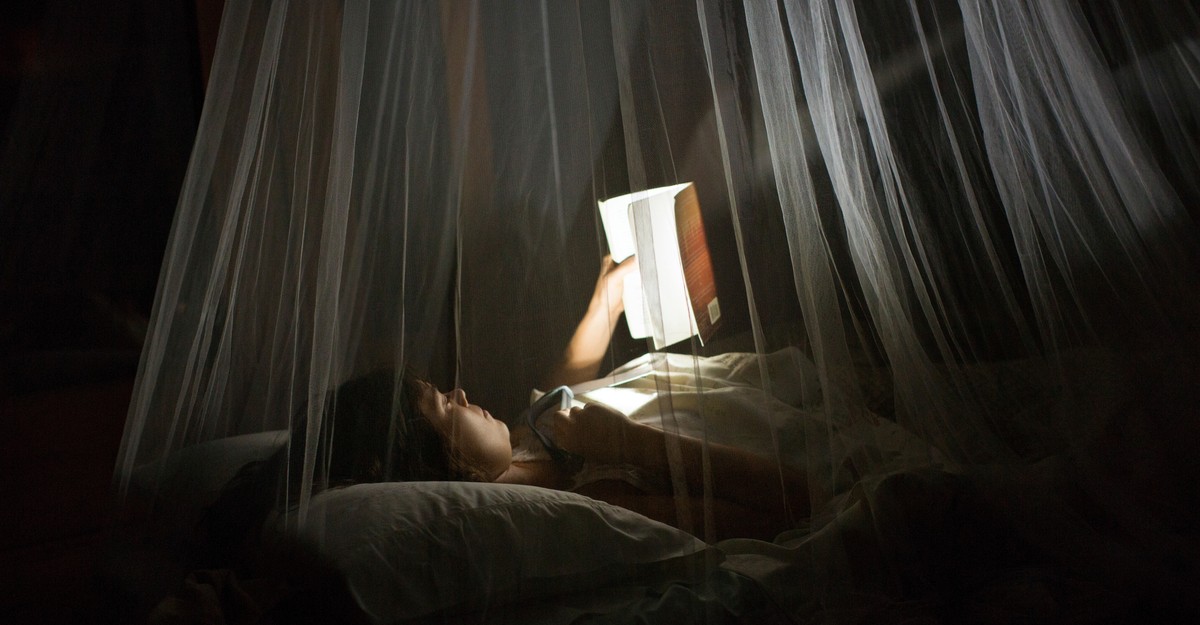

There are few things more agonizing than lying awake under the weight of exhaustion, yearning for sleep but watching the clock tick ever closer to morning. Modern conditions – too much blue light, too little exercise and a constant flow of caffeine, compounded by the psychological pressure of living in a world that seems to be falling apart – have made insomnia an epidemic.

In response, the wellness industry and influencers flooded our feeds with supposed cures for insomnia: mushroom powder, melatonin, meditation, computer glasses, Z-drugs, and benzodiazepines. I suffered from severe and chronic insomnia for days on end since my days at uni, and I’ve tried every remedy during that time. Through all those years of sleepless nights, literature has always been my greatest comfort, because the true torment of insomnia is loneliness: we have no choice but to spend the late, uninterrupted hours alone with our own thoughts. A book, however, can be another voice in the darkness, ready to soothe a restless mind. These novels and essays reflect such encounters with the self; even when we’re the only people up and about between dusk and dawn, they remind us that we have company in our solitude.

Diary of a lonelinessby May Sarton

Sarton’s apt title Diary of a loneliness chronicles the personal and professional anxieties of a middle-aged queer writer from her voluntary isolation in the remote New Hampshire village of Nelson, where she has retreated in the hope of “reopening the inner world.” The entries are alternately philosophical and banal: Sarton’s creative life is heavily influenced by the examination of her own emotional world and the close observation of her home and garden. Her attitude to solitude is strikingly ambivalent, as her freedom from social and professional obligations is tempered by daily confrontation with inner demons from which there is no distraction and no protection. “Here in Nelson I have come close to suicide more than once,” she writes, “and more than once I have come close to a mystical experience with the universe.” Sarton’s nocturnal life, like her poetry, fluctuates with the seasons and their changing states of mind—sleep is a sumptuous pleasure, but one that eludes her for days. A rich and sensual account of the life of the mind, Diary of a loneliness makes a long night seem shorter by savoring the joys of solitude as well as the torments.

The Anatomy of Melancholyby Robert Burton

Originally published in 1621, The anatomyas it is known among early modern scholars, is essentially a 17th-century self-help manual for mood disorders. It has been substantially revised and expanded; the New York Review of Books paperback edition is more than 1,300 pages long. It is a perfect companion for those with chronic insomnia, for the simple reason that you will never finish this book—unless, as in my case, it is an integral part of your doctoral dissertation. Many long passages are more than boring enough to lull you to sleep, but such a monumental work inevitably takes detours through interesting territory. You will find not only recommendations for holistic well-being of body and mind (though some of the methods may seem rather questionable to the modern reader), but also medical miracles, ritual madness, and even an early version of the multiverse theory. The anatomy has been waiting to be picked up and put down again and again for many years and has earned its place on my bedside table. And it is a small consolation because it shows that there are precursors to modern insomnia. In Burton’s estimation, insomnia can be both a cause and a symptom of despair: “Just as children are afraid of the dark, so melancholy people are afraid at all times,” he writes, because they take the darkness with them wherever they go.

From Robert Burton

With the night to the westby Beryl Markham

Markham was a fiercely independent woman. She grew up on her father’s horse farm in British East Africa in the early 20th century, where she learned to hunt, ride, fly and – above all – to rely on herself. An ambitious pilot, she was the first person to cross the Atlantic from Great Britain to North America alone and without stopping. With the night to the west recounts the events that led her to undertake this journey, from her first encounters with danger as a child in the land of lions to her night flights on search and rescue missions. Much like May Sarton, Markham viewed the longest, loneliest hours of her life—whether in the cockpit, in the wilderness, or on the horseback—as a test of endurance. Unlike Sarton, Markham had such an adventurous life that her memoir reads almost like a fairy tale; she whisks the reader away in her biplane. Her reflections on aviation are interspersed with beautiful descriptions of the earth and sky as she flies at night over Africa and around the world: “The air takes me away into its realm,” she writes. “The night envelops me completely, makes me lose touch with the earth, leaves me in my own little moving world, living with the stars in space.” Even if Markham’s book is too thrilling to put you to sleep, it is a dream to read.

Our share of the nightby Mariana Enriquez

In Enríquez’s dizzying, disorienting fable, something dark and malevolent feeds on human depravity. “Juan wanted to open the darkness,” she writes, “and the darkness would come and eat.” Little plot, but lots of atmosphere. Our share of the night Defies every narrative convention, plunging the reader into a stagnant, black fever dream that persistently blurs the line between history and fantasy. In its phantasmagoric allegory of the sweeping horrors of Argentina’s military dictatorship, members of the mysterious order torture and mutilate people chosen as mediums to summon the ravenous darkness and beg it for immortality. But when the newest medium rebels, the effects ripple through the waking and sleeping worlds. This novel knows the lonely agony of communing with the night.

The Third Hotelby Laura van den Berg

Van den Berg’s slim and disturbing novel The Third Hotel follows Clare, a young widow, to Havana for a film conference she was planning to attend with her husband. But he was hit by a car during a nighttime stroll, and on the very first page she admits to having “experienced a reality distortion.” As Clare tries to navigate Cuba and her husband’s alienating academic world, van den Berg captures both the chimerical quality of traveling alone in a foreign land and the sleepwalking trance of grief in which meaning and significance seem to collapse. Then, when Clare’s dead husband turns up on a street corner—apparently alive and apparently well—the novel takes a turn toward the unreality of a lucid dream, through quietly compelling prose. Clare is no passive sleeper; she is an active player in the unfolding metaphysical game, even if she doesn’t know the rules.

Desert Solitaire: A season in the wildby Edward Abbey

“June in the desert. The sun roars down from its orbit in space with a wild and sacred light, a fantastic music in the head,” wrote Abbey in the late 1950s as a park ranger in what was then Arches National Monument. Desert Solitairetaken from Abbey’s diaries, became a cult classic of the early environmental movement. The author is a misanthropist of the first order who thrives in solitude; his disdain for tourists and developers is matched only by his awe of the arid landscape. His wandering prose soothes a restless mind with hypnotically repetitive passages: my favorite chapter, simply titled “Stones,” begins with a long list of poetic scientific names for various types of rock. If it doesn’t put you to sleep (I recommend the audiobook, delivered with sonorous grace by Michael Kramer), the tall tale it segues into may keep you awake for the next half hour. Readers who finish the chapter will be transfixed by the imaginative splendor of Abbey’s language as he describes the hallucinations of a lost teenager confused by sunstroke and a handful of poisonous berries that he chokes down in desperation.

The name of the Roseby Umberto Eco

Eco’s medieval crime novel defies interpretation like a particularly thorny dream. “A narrator should not provide interpretations of his work,” Eco explains in the postscript to his 1980 debut novel. “Otherwise he would not have written a novel that is a machine for generating interpretations.” The The name of the Rose rejects an easy solution, is fitting: This is a book about books. The Order of Saint Benedict has enlisted the investigative instincts of Franciscan friar William of Baskerville after the grisly murder of one of its monks. Eco’s narrative structure mimics the rhythm of life in the monastery, where “the monk must rise in the dark and pray long in the dark, waiting for the day, lighting the shadows with a flame of devotion.” But the long hours of night are not just a time of prayer and reflection, as any insomniac knows. In Eco’s enclosed, claustrophobic world, secrets, sins, and murder lurk in the monastery after sunset. This offbeat mystery about a locked room where good and evil meet and old books are worth killing for is an ideal distraction for a racing mind – instead of worrying about what you must do tomorrow, you’ll drift off wondering who did it.

If you buy a book through a link on this page, we will receive a commission. Thank you for your support The Atlantic.