From Machu Picchu to the Louvre – a new book travels to sacred sites of art and ancient history

Today, “sacred” is a broad and liberally used term. Sports fields are sacred, bedrooms are sacred too. The English word originated in the late Middle Ages to refer to the bread and wine of the Eucharist, but its Latin root “sacer” had a dual meaning, referring both to places or objects capable of causing spiritual pollution and to those not intended for divine use.

The Romans were keen to isolate places from the “profane” and bring them under state control. However, towards the barbaric sanctuaries they encountered, they were at best indifferent (Stonehenge) and at worst destructive (the Temple of Jerusalem). One only has to think of the protests against the Keystone Pipeline XL or the fate of the Benin Bronzes to see that such tendencies persist.

Inside holy sites. Photo courtesy of Taschen.

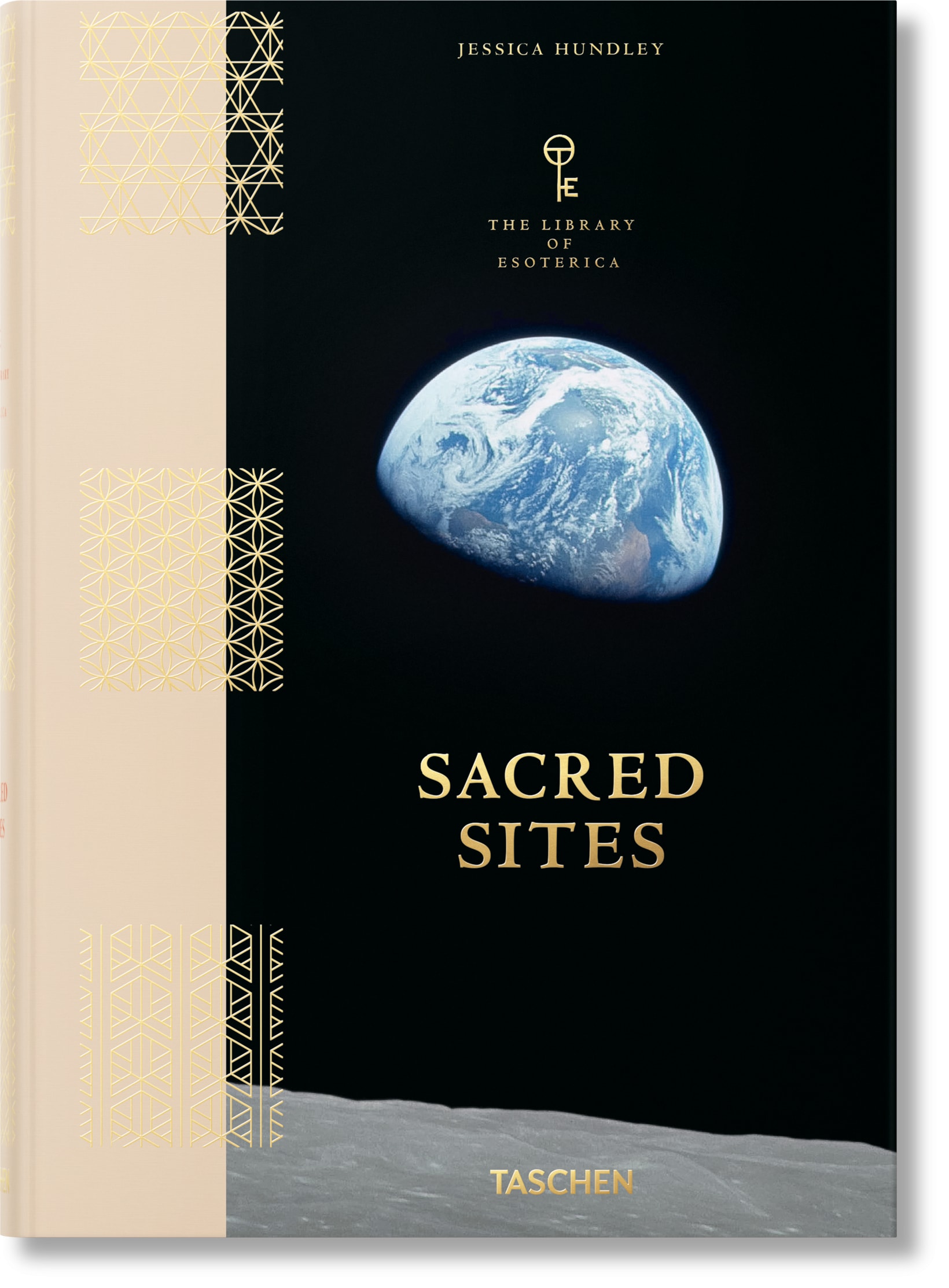

If there is a universally sacred place, it is the Earth itself. This is the starting point for Holy placesthe latest colorful tome in Taschen’s “The Library of Esoterica” series. On the cover is Earthrisea 1968 photograph by astronaut William Anders depicting our planet as a vulnerable object of wonder.

Buckminster Fuller, Building Construction/Geodesic Dome, United States, 1951. Photo courtesy of Taschen.

The project is comprehensive: it aims to present countless places that have been considered sacred by humans from the Neolithic period to the present day. “This volume traces a sacred path from rugged stone temples to transcendent works of modern architecture,” wrote editor Jessica Hundley in the foreword, “and honors the collective history of places sanctified by human worship.”

Inside Holy places. Photo courtesy of Taschen.

This journey begins with a selection of the greatest architectural achievements of global civilization, passing through the Great Sphinx, Stonehenge, Machu Picchu, Jerusalem’s Western Wall, and Sagrada Familia, and offering brief biographical information on each of these sites. Lesser-known sights include the Minaret of Jam, a 200-foot brick tower built by the Ghurids 800 years ago, and the 12th-century Pueblo cliff dwellings in what is now Colorado.

Mohammadreza Domiriganji, Ceiling of the Vakil Mosque, Shiraz · United Arab Emirates · 2014. Photo courtesy of Taschen.

This is followed by “Earth Body,” a chapter dedicated to humanity’s eternal veneration of the earth and nature. It introduces earth, stone, water, sky, mountains, forests and groves, and caves and grottos, and presents artistic representations for each of these areas. We encounter Van Gogh’s sky-blue skies, Georgia O’Keeffe’s twisted animal bones, and Caspar David Friedrich’s romantic classic.

In addition to earth worship, Sacred Sites proposes body worship as “perhaps the oldest of all spiritual practices.” Greek, Egyptian, Mesoamerican, and Hindu fertility temples provide physical evidence, as do artworks ranging from Greek colossal phallic sculptures to medieval manuscripts and Qing Dynasty erotica to contemporary body art.

Olafur Eliasson “The Weather Project · Iceland/Denmark”, 2012. Photo: courtesy of Taschen.

In “Architecture of the Spirit” we encounter the dominant and recurring forms and geometries of man-made sacred buildings. There are the pyramids that stretch across Egypt, Mesoamerica and the Louvre, the domes of Turkish crypts and the Taj Mahal, the circles of Buddhist shrines, Venetian pleasure gardens and Ethiopian village houses.

Yann Arthus-Bertrand “Moshav farm (cooperative village) in Nahalal, Jesrael Plain, Israel.” Photo: Taschen

The final chapter of Sacred Sites is largely devoted to the ways in which the “landscapes of fiction and myth, of folk tales and songs” of artists and communities became reality. From the fantastical visions of Hieronymus Bosch, Denis Villeneuve and William Blake, we move to the geodesic domes of the Osaka Expo, to photographs of rigorously planned urban areas and to those of towering libraries, Olafur Eliasson’s artificial sun. In each we find a hint of a promise that paradise, as the book promises, can be found.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay up to date in the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter and receive breaking news, insightful interviews and astute critical views that drive the discussion forward.