Q&A: What past environmental successes can teach us about solving the climate crisis | MIT News

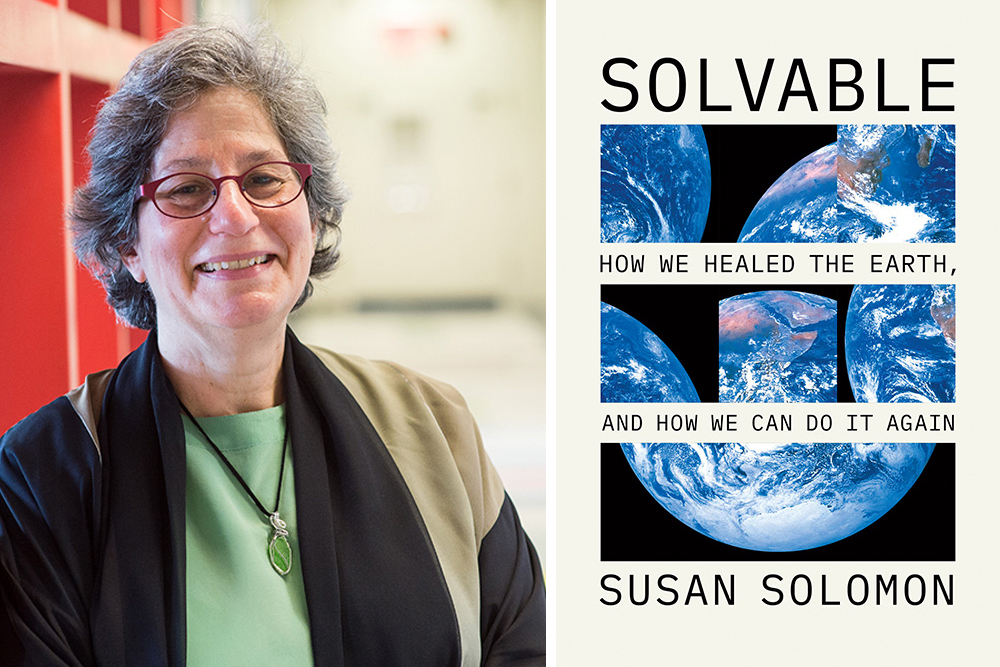

Susan SolomonProfessor of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) and Chemistry at MIT, played a crucial role in researching how a class of chemicals known as chlorofluorocarbons caused a hole in the ozone layer. Her research was fundamental to the creation of the Montreal Protocolan international agreement from the 1980s that calls for the phasing out of products that release chlorofluorocarbons. Since then, scientists have documented signs that the Ozone hole recovers thanks to these measures.

Solomon, the Lee & Geraldine Martin Professor of Environmental Studies, has witnessed this historic process firsthand and knows how people can come together to create successful environmental policy. Using her story and other examples of success – including combating smog, abolishing DDT and more – Solomon’s new book draws parallels from then to now as the climate crisis comes into focus. “Solvable: How We Healed the Earth and How We Can Do It Again.”

Solomon took a moment to talk about why she chose the stories for her book, which students inspired her, and why we need hope and optimism now more than ever.

Q: You have witnessed first-hand how we have changed the Earth and how international environmental policy is created. What prompted you to write a book about your experiences?

A: Many things, but one of the most important is the things I see when I teach. I taught a course here at MIT for many years called “Science, Politics, and Environmental Policy.” Because I always focus on how we actually solved problems, students leave that course full of hope, like they really want to continue to study the problem.

I notice that students today are growing up in a very contentious and difficult time where they feel like nothing ever gets done. But things are getting done, even today. When you look at how we’ve done things in the past, you can really see how we can do things in the future.

Q: In your book, you use five different stories as examples of successful environmental policy and at the end you talk about how we can apply these lessons to climate change. Why did you choose these five stories?

A: I chose some of them because my professional experience brings me closer to these problems, such as ozone depletion and smog. I covered other topics because I wanted to show that we have actually achieved a lot in the 21st century – this is the story of the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, a binding international agreement on certain greenhouse gases.

Another chapter is devoted to DDT. One of the reasons I included it is because it had a huge impact on the birth of the environmental movement in the United States. It also shows how important environmental groups can be.

Lead in gasoline and paint is another. I think it’s a very moving story because the idea that we’re poisoning millions of children and we don’t even know it is so incredibly sad. But it’s so encouraging that we recognized the problem, and that happened in part because of the civil rights movement, which made us realize that the problem affects minority communities much more than non-minority communities.

Q: What surprised you most while researching the book?

A: One of the things I didn’t realize, although I should have, was the outsized role played by a single senator, Ed Muskie of Maine. He made fighting pollution his big issue and devoted incredible energy to it. He clearly had the passion and wanted to do it for many years, but until other factors helped him, he couldn’t. That’s when I began to understand the role that public opinion plays, and that policy is only possible when public opinion demands change.

Another thing that was unique about Muskie was the way his commitment to these issues required strong science. When I read what he said in his testimony to Congress, I realized how highly he valued science. Science alone is never enough, but it is always necessary. Over the years, the science got much stronger and we developed ways to evaluate what the scientific wisdom actually is from many different studies and many different views. That’s what scientific assessment is all about, and it’s critical to making progress in the environmental field.

Q: In your book, you argue that for environmental protection to be successful, three things must be in place, which you call the three Ps: a threat must be personal, perceptible and practical. Where does this idea come from?

A: My observations. You have to perceive the threat: in the case of the ozone hole, you could perceive it because those false-color images of ozone loss were so easy to understand, and it was personal because there are few things more terrifying than cancer, and a reduced ozone layer leads to too much sun, which leads to more skin cancer. Science has a role to play in communicating what is easy to understand for the public, and that’s important so they perceive it as a serious problem.

Today we are aware of the reality of climate change. But we also see that it is a personal issue. Many more people are dying from heat waves now than in the past; for example, the Boston area has terrible problems with flooding and rising sea levels. People are aware of the reality of the problem and feel personally threatened.

The third P is practical: people need to believe that there are practical solutions. It’s interesting to see how the battle for people’s hearts and minds has shifted. There was a time when the skeptics were just attacking the whole idea that the climate is changing. At some point they decided, “We’d rather accept it because people are noticing it, so let’s tell them it’s not caused by human action.” But now it’s clear enough that human action plays a role. So they’ve moved on to attacking the third P, which is that it’s somehow not practical to have any solutions. That’s progress! So what about the third P?

In my book I have tried to show some of the ways in which the problem has been tackled in a very practical way over the last ten years and will continue to develop in that direction. We are on the verge of success and we just have to keep going. People should not fall into eco-despair; that is the worst thing you could do because then nothing will happen. If we carry on at this pace, we will certainly get to where we need to be.

Q: That fits in very well with my next question. The book is very optimistic. What gives you hope?

A: I am optimistic because I have seen so many examples where we have succeeded, and because I see so many signs right now of a movement that will push us in the same direction.

If we had continued as we did in 2000, we would be looking at 4 degrees of warming in the future. Right now, I think it’s 3 degrees. I think we can get to 2 degrees. We really need to work on it and get serious in the next decade, but globally over 30 percent of our energy currently comes from renewable sources. That’s fantastic! Let’s just keep going.

Q: In your book, you show that environmental problems cannot be solved by individual action alone, but that political and technological push is needed. What individual actions can people take to drive these larger changes?

A: One key point is to eat more sustainably, choose alternative modes of transport like public transport or reduce the number of trips. Older people tend to have retirement savings investments. You can shift these into a social fund and withdraw them from index funds that end up funding companies you may not be interested in. You can use your money to apply pressure: Amazon has been under enormous pressure to reduce its plastic packaging, especially from consumers. They just announced that they will no longer use those plastic pillows. I think there are many ways in which people really matter and we can make more matter.

Q: What do you hope people take away from the book?

A: Hope for their future and determination to do their best and strive for it.