Does a patient’s income affect the value of their care?

Wealthier people have many advantages when it comes to health care: they are more likely to be insured, have more access to specialty care, and live longer and healthier lives on average. But are higher-income patients also at greater risk of overuse?

Measuring high-value and low-value care by income

In a recent study in Health mattersResearchers Sungchul Park of Korea University and Rishi K. Wadhera of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center examined the relationship between patients’ income and the receipt of certain high- or low-quality services.

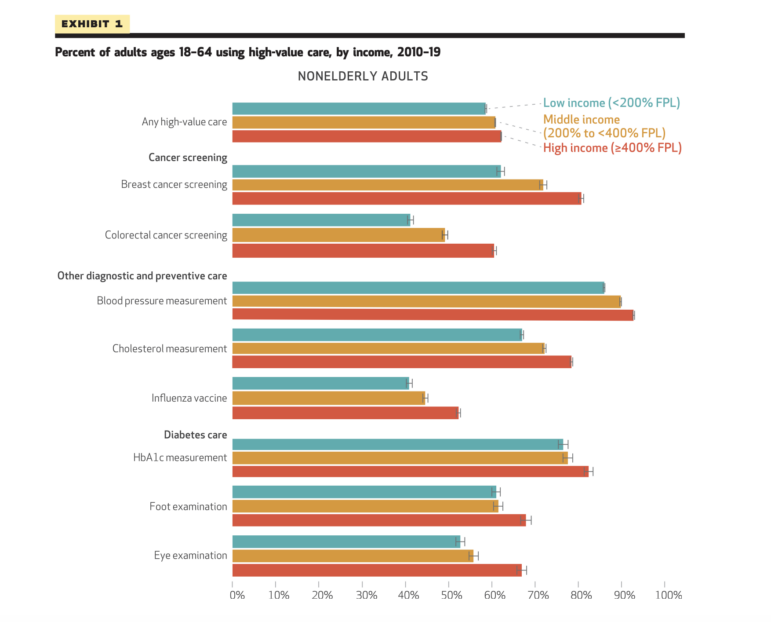

Using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) from 2010 to 2019, the authors compared rates of eight high-value and nine low-value services among patients by income. High-value services included certain cancer screenings, blood pressure measurements, cholesterol measurements, flu shots, and diabetes treatments. Low-value services included antibiotics for colds and flu, benzodiazepines for depression, opioids for back or headaches, and certain imaging tests for back or headaches.

Income was categorized based on family income into less than 200% of the federal poverty level, 200-400%, and 400% or more. The results were also separated by older and non-elderly adults because most older adults are insured by Medicare. The researchers controlled for age, sex, race, census region, insurance coverage, and other patient characteristics.

Higher income, higher value

They found that high-income adults were more likely to receive high-quality services, particularly in the non-elderly group. For example, the rate of colorectal cancer screening was almost 20 percentage points higher among high-income non-elderly adults than among low-income adults.

However, the results for low-value care were mixed. While non-elderly, high-income patients were more likely to receive antibiotics for colds and flu, low-income patients were more likely to receive other low-value medications such as opioids for back pain and benzodiazepines for depression. Opioids for back pain were also used significantly less frequently by high-income older adults compared with low-income older adults. The authors note that this finding is “consistent with existing evidence that opioid prescription rates are higher in low-income communities,” which is concerning.

Behind the variation

How do we explain these differences between high-value and low-value care by income? Although the authors accounted for differences among patients in terms of insurance status and education, there are many other mechanisms that can affect our quality of care. The authors cite “a shortage of health care providers, long distances to health facilities, and limited access to transportation in low-income communities” that could reduce receipt of high-value care.

Low-income adults may also be less likely to receive high-quality treatments because of the cost. Even for insured patients, out-of-pocket costs can be prohibitive. For example, the cost of a preventive colon cancer screening should be fully covered, but if polyps are found, a follow-up colonoscopy may be billed as a “diagnostic” test, which can cost patients thousands of dollars. With surprise bills popping up everywhere, it’s no wonder people avoid preventive screenings, even when they’re recommended by their doctor.

Patient behavior or provider perceptions may impact receipt of low-value treatments. Providers may be more likely to prescribe low-value antibiotics to high-income patients because these patients are more likely to ask for them or because they fear that doing so would negatively impact patient satisfaction.

Finally, differences in provider practices also play a role. Research from the Lown Institute and others shows that prices for low-value services vary widely between hospitals and health systems. If low-income patients tend to go to certain hospitals (which is often the case in segregated hospital markets) and those hospitals provide more low-value services, this could explain some of the differences.

We still don’t know much about the relationship between income and quality of care. The authors recommend further research “to better understand these mechanisms and to develop policies and interventions that promote the use of high-quality care and prevent the use of lower-quality care at all income levels.”