“It’s not about pain”: The death-defying performance art of Miles Greenberg

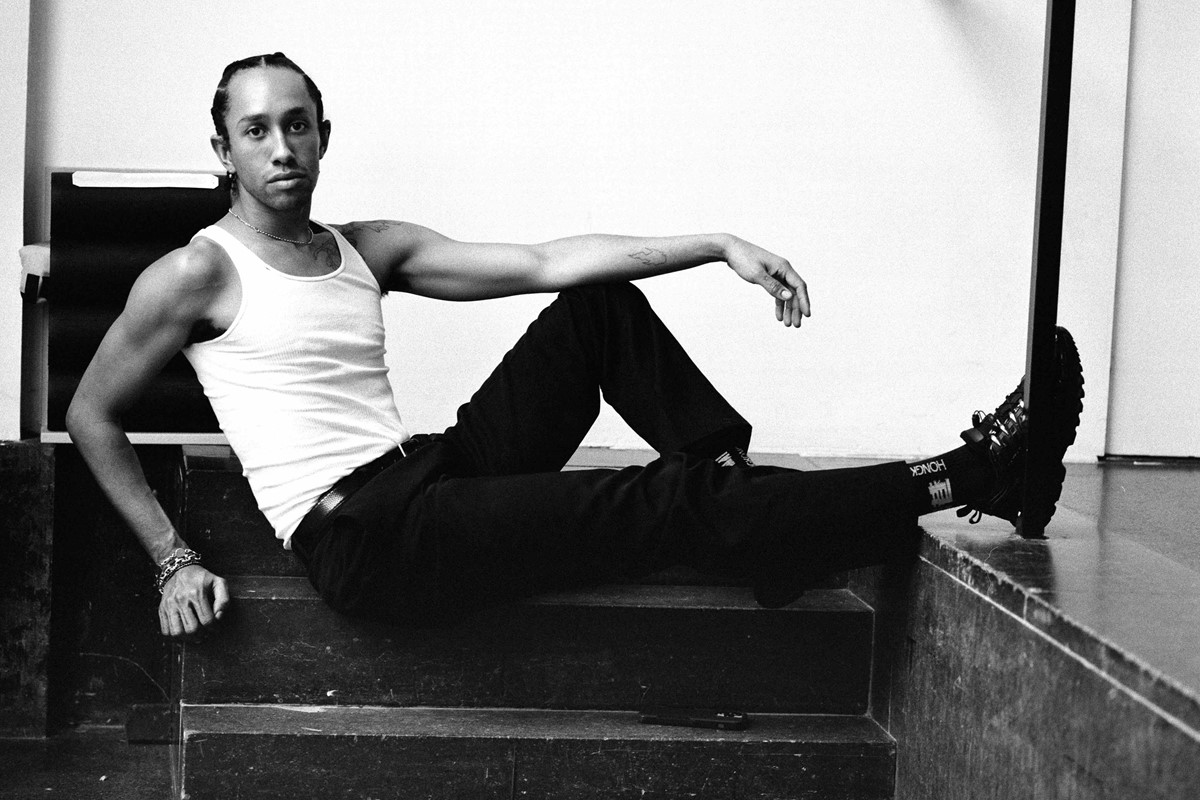

Cover imageMiles GreenbergPhotography by Eva Roefs

The art historian, curator and author Alayo Akinkugbe is behind the popular Instagram page A black art historywhich highlights overlooked black artists, models, curators and thinkers from the past and present. In her column for AnOthermag.com titled Black looksAkinkugbe examines a spectrum of black perspectives from all artistic disciplines and the entire history of art and asks: How do black artists see and respond to the world around them?

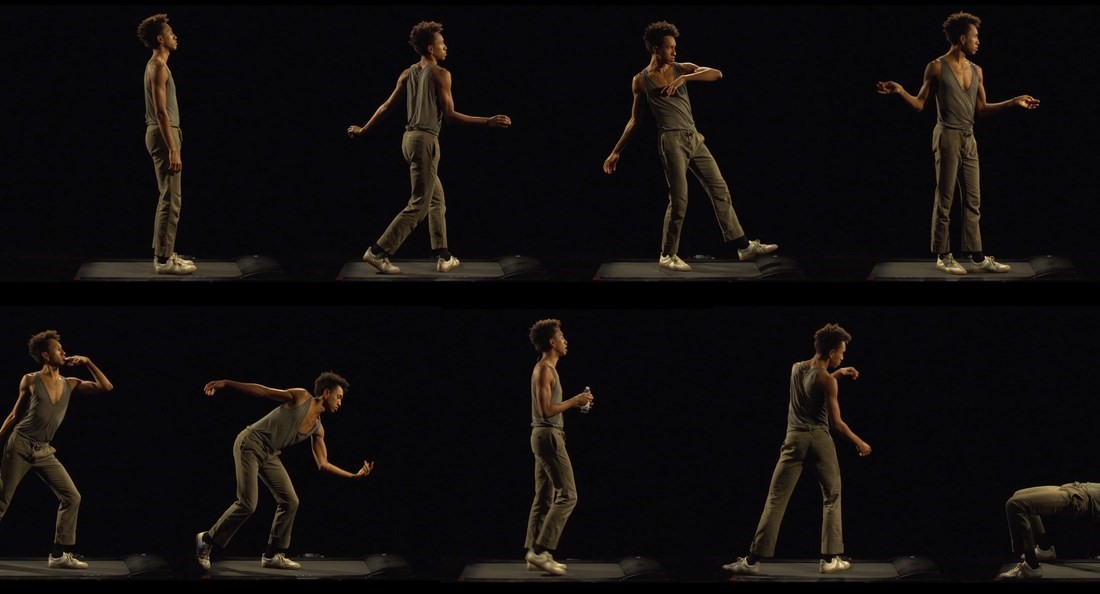

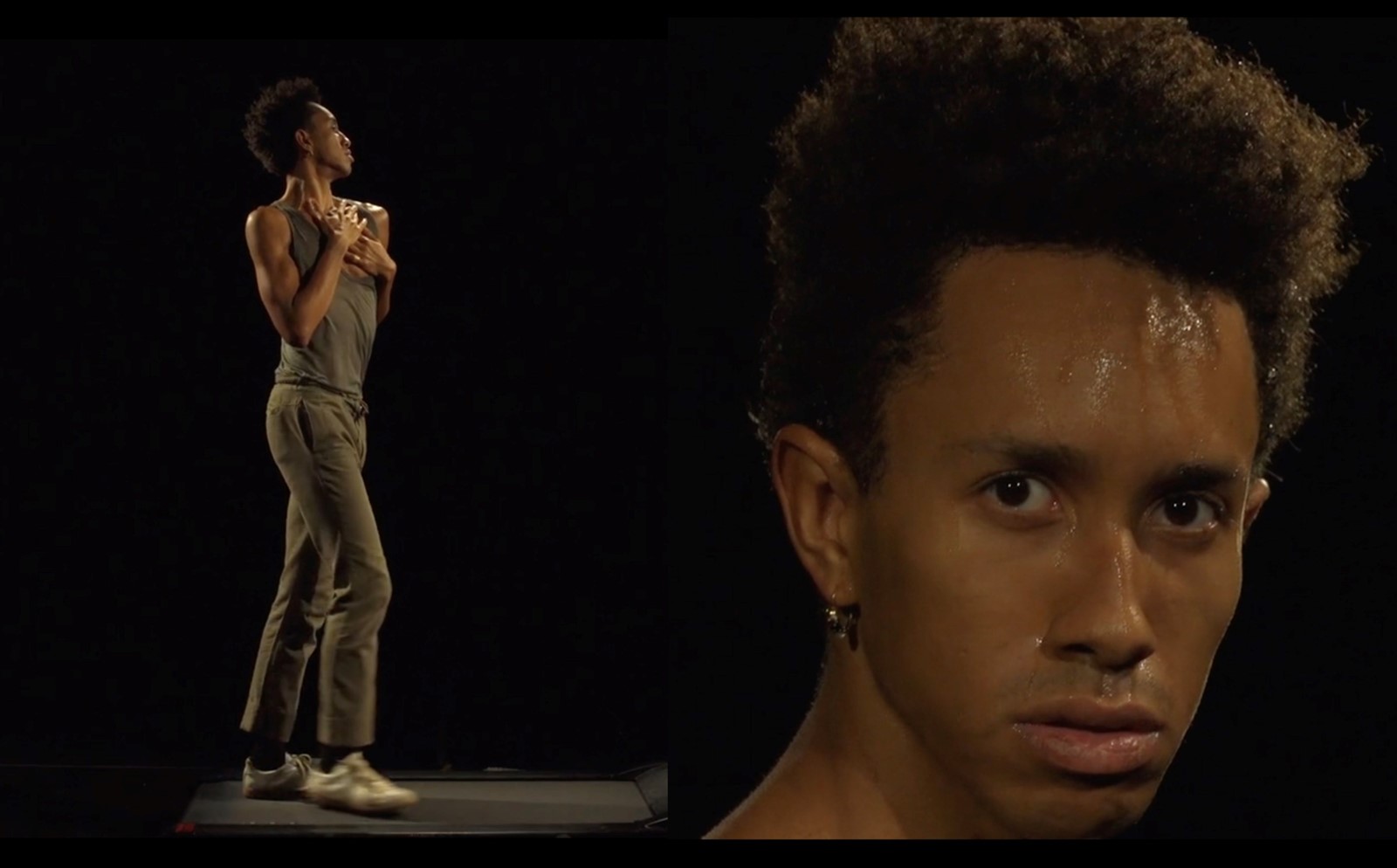

Miles Greenberg is the New York-based Canadian artist known for his grandiose and exhausting long-term performances. In his works, Greenberg and other performers often appear in costumes, with oiled skin, alien-looking white contact lenses or smeared with jet-black body paint. But in Oyster knifewhich he describes as “the hardest thing (he) has ever done with (his) body.” Greenberg wore “civilian clothes.”

This performance, in which Greenberg walked on a conveyor belt for 24 hours straight without stopping, was originally created in July 2020 in collaboration with the Marina Abramovic Institute. The film of the performance celebrates its UK premiere at the London gallery Albion Jeune, together with Douglas Gordon’s 24 Hours Psycho (1993) in the exhibition Twenty-four Twenty-four.

Below, Miles Greenberg talks about the influence of authors such as Zora Neale Hurston, his odes to the anonymous “Moor” sculptures in Venice, and how he learned to sculpt with marble.

Alayo Akinkugbe: Let’s start with the name of your performance that will be shown at Albion Jeune. Oyster knife. Where does this title come from?

Miles Greenberg: I wrote this piece very quietly in my childhood bedroom while I was in quarantine in 2020, the day Ahmaud Arbery was shot (while running). I was thinking about this very simple cardio gesture, about a kind of poetry to strip away the violence and find a more solemn ritual for an ending like this. This was a very private backdrop for (Oyster knife); I haven’t really spoken much about it publicly until now. That was the first trigger.

It was a very strange time, because I felt like my own quiet fear, this constant, underlying fear of the police, of violence, of an oppressive dynamic, was very private, and my own head had suddenly exploded all over the internet, and everyone was constantly asking me if I was OK, about something I thought was a secret. The title comes from Zora Neale Hurston’s essay, How it feels to be colored. I usually don’t know what my work is about until I’ve shown it. I had a lot of vague feelings that were solidified by this piece.

AA: At the age of 17, you left school and began working as an artist. What made you decide to pursue an independent path at such a young age?

MG: At school I realised I knew a lot of the work we were talking about. I had seen some of it with my mother, who took me everywhere and gave me training in the field. I knew instinctively that (school) wasn’t for me. I had just started working and I was offered a few group shows that weren’t connected to school, so I thought I’d just try a practice for a year. Then I was offered a residency in Beijing, so I pursued that. Then I did a residency in Paris and stayed there for what turned out to be three and a half years.

“It is important to emphasize that the work is not about pain… It is certainly not about my black pain and it is not about this eternal theater of black death in which we live” – Miles Greenberg

AA: What do you find so appealing about endurance performance and pushing your body to its limits? Have you always wanted to perform well?

MG: That’s completely irrelevant. I’m not particularly interested in the performance (aspect). My brain works like a sculptor, although performance has always fascinated me because our emotional reflexes are so strong and powerful when we see other human bodies. I’ve always been very interested in classical sculpture, when I’ve seen Greco-Roman statues, for example. I think the heart reacts very quickly when you see limbs and torsos and things that you recognize.

Viscerality is something I’ve always wanted to play with. I love the immediacy of performance, I love that the audience is already consuming it while you are doing it. I was first made aware of it by Marina (Abramović) at (the exhibition) The artist is present. When I was 12, my mom took me to this show at MoMA and it kind of changed my life. But I’m also making marble sculptures at the moment, which I’m really passionate about. I’m learning how to carve.

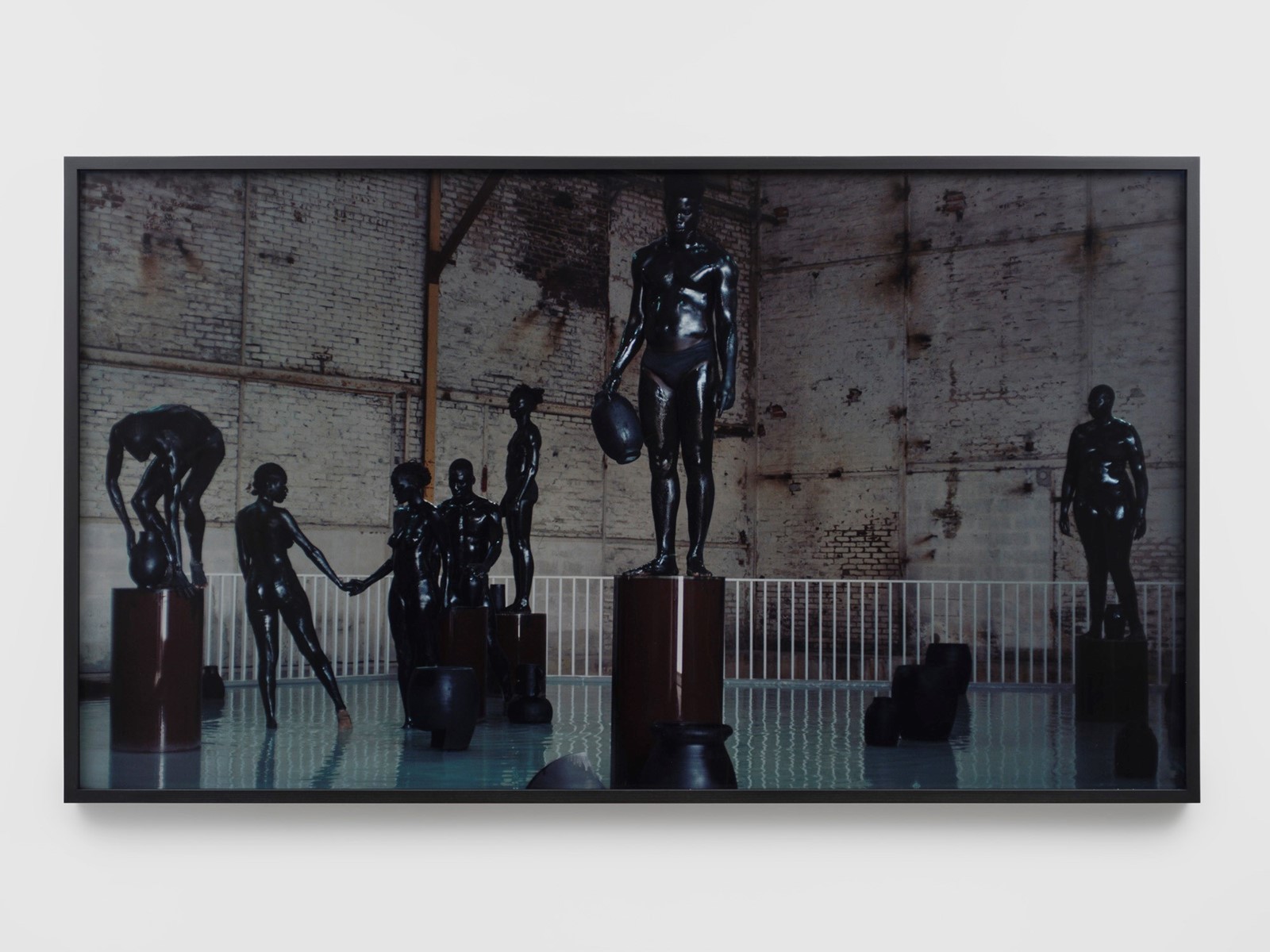

AA: You often refer to statues of “Amauren” in your work, as in your recent performance Sebastian, which was carried out in the opening week of the Venice Biennale. Why do you use these kinds of images?

MG: I remember going to the Ca’ Rezzonico museum in Venice with my mother when I was nine. There were dozens of these ebony statues of slaves and soldiers from the 17th century. They were extremely elaborate, but the figures were parts of tables or chairs, clinging to the arms of the seats.

Their (functions) were structural; some of them were pillars and held the space together, but they are the only figures in this space that don’t have a name or an identity. Any representation of a white person, whether it’s a noble or a mythological figure, can be named, each of them has a story, and somehow that just didn’t reach black people. When I saw these figures, something shifted in my brain chemistry, and I remember it being equally inspiring and traumatizing at the same time.

I think of Kerry James Marshall and so many artists who use blackness as a metaphor, who have taken it and exaggerated it. I guess I’m just trying to live in that universe and find my own language and create poetry around the theme of “a shadow.”

AA: And Oyster knife will be shown in London together with the renowned work of video artist Douglas Gordon 24 Hours Psycho (1993).

MG: I’m really excited to be competing with Douglas Gordon on this show. He just has a really cool mind. The first time I visited his studio in Berlin I was about 18. He walked around with an axe in his belt the whole time and I just stared at it until at one point he suddenly pulled it out from 10 meters away and threw it at the farthest wall where it landed right in the middle of a print. I just thought, “Holy shit.” I’m excited to be in dialogue with his work.

AA: How is Oyster knifeas you previously described it, “a love letter to the performance art of the 1970s and in particular to the great black endurance pioneers such as Senga Nengudi, Pope.L and David Hammons”?

MG: Oyster knife was first presented by the Marina Abramović Institute. Marina and I discussed it beforehand and thought about what I should wear. It was the first piece I ever did in civilian clothes. She told me that (performance artists) in the ’70s wore either dirty white, dirty black or dirty grey. So I chose dirty grey. (The performance) was extremely stripped down, extremely simple, extremely straightforward, but also extremely difficult. It remains the hardest thing I have ever done to my body.

It’s important to stress that this work is not about pain. It’s not about suffering. Ultimately, this work, even though it originated with the murder of a black man by racist militias, is not about pain. It’s certainly not about my black pain, and it’s not about this perpetual theater of black death that we live in. Pain and discomfort, like ecstasy and pleasure, can be used as a gateway to understanding our bodies. It’s really, really about life.

Twenty-four Twenty-four by Douglas Gordon and Miles Greenberg is on display at Albion Jeune in London until July 28, 2024.

Related Posts

The best bulk packs at Sam’s Club to save money, from Tide Pods to Shampoo

Israeli troops and warplanes attack northern Gaza – Naharnet