The memory of the recent drought disaster must not fade – Marin Independent Journal

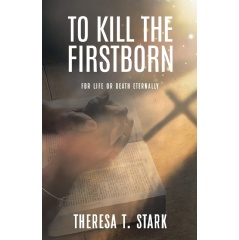

The dropped water level marks the edge of the Soulajule Reservoir dam west of Novato, Calif., on Thursday, Aug. 5, 2021. (Alan Dep/Marin Independent Journal)

Two years of life-affirming, transformative rains have filled the reservoirs. No more unflushed toilets sacrificed to environmental protection. The lush green hills of the past few months are turning a dignified brown. We have so much water that any memory of parched, cracked lawns is a thing of the past.

That wasn’t so long ago. Even in normal years, the seven reservoirs that provide 75% of our water barely last for two years. But in 2021, they were running dry. This year, a surprise atmospheric river event in October prevented the wolf from leaving the door. And that wasn’t the first time.

Since 1976, Marin has experienced 24 years of drought. Drought has accelerated this century, with 17 of the last 24 years being drought. Drought may have eased a little in recent years, but it will return. It always does.

Lack of rain is not the only looming problem for the Marin Municipal Water District. Storage capacity and access are also weak points in the system. Years of reluctance to build a more resilient water supply, coupled with blind devotion to conservation and strict restrictions on water use, have exacerbated the problems. In addition, the 25% of our water we get from Sonoma, which flows through the newly upgraded Kastania pump, could be at risk if Sonoma’s water becomes scarce. Sonoma Water will certainly prioritize its own growing communities.

It’s not just the cost of imported water that’s concerning. Miles of rusted, leaking water pipes need to be replaced. Material and labor costs have increased. The ecological health of the watershed needs to be protected to maintain its biodiversity, water quality and yields. All of this could too easily be lost with the toss of a lit cigarette. Just thinking about how a major fire could turn our pristine reservoirs into murky pools makes me sick. Mitigating wildfire risk is imperative. All of this costs money.

By 2022, MMWD’s operating costs were higher than ever and financial reserves were at drought levels, with a deficit of $31 million. In other parts of California, water managers proposed tying rate increases to the consumer price index. The Contra Costa Water District pioneered this concept in the 1980s and is one of the most financially sound in California.

MMWD has not followed suit. Before last year, for nearly 30 years, it had only sporadically, if at all, increased tariffs or introduced new fees. We all know today that this tactic can lead to sharp and painful increases to offset cost-of-living and other shortfalls, leaving limited alternative sources for financially replenishing the necessary reserves.

Perhaps the main thought on the minds of some MMWD directors at the time was that voters do not like wage increases. Two former board members, who served a total of 43 years, left the company in 2022.

This year, three new directors came on board. They were aware of the problems they faced, but they were also willing to look for new and innovative solutions to solve them.

While they still respected the importance of water conservation, they also wanted to explore other options that could make Marin’s water supply more robust, including greater storage capacity, advanced recycled water technologies, and more environmentally friendly desalination. They knew that by significantly improving our water infrastructure, we would survive the inevitable droughts and storms of the coming decades. Realistically, they knew none of this could be done without raising prices. As expected, prices were raised again this month.

As of 2022, the MMWD has failed to deliver a viable solution to water supply stability or prevent a budget crisis. We must not forget where we were a few years ago when we were still in the throes of these crises. While this is an important election year on so many levels, the elections near us are no less important. Pay attention in the coming months and go vote on November 5th.

Kristi Denton Cohen of Mill Valley is co-founder of the Marin Coalition for Water Solutions.