Gender discrimination does not always end with the death of a woman. Newspapers have long treated women differently in terms of the number, wording and presentation of obituaries.

Since the 18th century, newspapers have published short obituaries with basic facts. These notices were often submitted by family members or funeral directors and placed near the advertising columns.

Obituaries, on the other hand, are stories with more details about a person’s life – the kind of tributes that might catch a stranger’s attention. Usually written by newspaper staff, they require a certain amount of news judgment: What or who would readers find interesting?

This value judgement has determined who is worthy of an obituary for centuries. And for years, the exclusion of women from the public eye meant that they were rarely included in obituaries.

Not all obituaries are flattering. Nevertheless, they signal that someone was important to society.

“True femininity”

Just before the Civil War, in the early years of The New York Times, the number of obituaries the paper published for women and men was nearly equal, according to historian Janice Hume. But in her book on obituaries from 1818 to 1930, she says that only 8% of the paper’s obituaries at the time honored women.

Nineteenth-century obituaries were typically white and upper-middle-class for both sexes. Dark-skinned women or women from lower classes were only mentioned if they met an unusual fate or lived to an unusually old age.

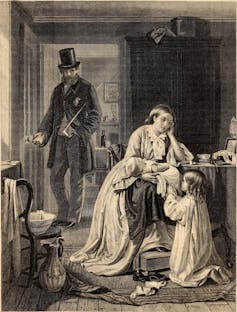

The 19th century was the height of an ideal called the “cult of true femininity,” a component of my research on female engagement. Middle- and upper-class culture in the United States valued the idea that men and women had different spheres of life—and women’s was for the home. The world of business and politics was often portrayed as corrupt, and society assigned women the role of promoting moral values in the home.

Flickr via Wikimedia Commons

These messages set expectations for women’s behavior—emphasizing piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity—and influenced their portrayal in the media. Women heard about these virtues in church and read about them in magazines.

The language used to describe women in obituaries conformed to these ideals. Hume’s analysis showed that obituaries tended to describe women using terms such as “pious,” “virtuous,” “obedient,” “innocent,” “useful,” and “kind.”

In obituaries, women were identified primarily by their connection to men: their husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers. Later in the 19th century, obituaries of women might include a list of their public achievements—but only if these did not compromise their “true womanhood.”

Women’s history blog via Wikimedia Commons

For example, several newspapers across the country reported the 1870 death of Charlotte Lozier, an early graduate of the New York Medical College for Women. Her name had previously appeared in the newspapers because of her activities as a prominent physician, lecturer, and women’s rights activist. After her death, an article in the Worcester Daily Spy mentioned Lozier’s profession but emphasized her morals, religion, kindness, and family life.

“Her house was the refuge of some of the choicest minds of New York society, and the hospitality was marked by a grace and kindness that no one who had once enjoyed it would ever forget,” the author explained.

Double standards

The nature of obituaries did not change much when the women’s suffrage movement brought more women into the public eye – partly due to competition among daily newspapers. Stories had to attract readers, so it was crucial that obituaries were prominent and interesting. Women were not considered attractions at the time.

Hume found that in 1930, fewer than 20% of obituaries in the New York Times and Chicago Tribune were women. A study conducted in the 1970s found similar percentages. This study also showed that obituaries about women were, on average, shorter than those about men and were less likely to include a photograph.

A 2004 study of obituaries confirmed that male obituaries were more likely to include photographs. It also added that female obituaries were more likely than male obituaries to include photographs of the person at a younger age than they were at the time of their death.

Age differences in women’s death photographs increased in the late 20th century, according to research by social workers at Ohio State University: a worsening double standard that equates women’s beauty with youth.

Make amends for injustice

The New York Times lamented the unequal treatment of women in obituaries and began using a diversity analysis tool five years ago to ensure that at least 30 percent of the people mentioned in its obituaries were women.

In addition, the Times created “Overlooked”: a series of stories about remarkable people whose deaths were never reported in the newspaper. Although these weekly features focused on women, they also featured people whose deaths were ignored due to other forms of discrimination.

Subjects include Indian women’s rights activist Hansa Mehta, Japanese-American journalist Bill Hosokawa, who was sent to an internment camp during World War II, African-American journalist Ida B. Wells, who brought lynching to the world’s attention, and tap dancer Henry Heard, an activist for people with disabilities.

Honors today

These are steps to balance the number of women honored in major newspapers. In addition, at a time when newspapers are receiving less revenue from advertising and subscriptions, obituaries that families pay to publish have become a valuable source of revenue for smaller newspapers because they make their obituaries more comprehensive.

Although these stories are written by relatives, they are considered obituaries because they go beyond the basic facts of a death notice. Yet even obituaries submitted by families and funeral homes are biased.

In a 2017 study, researcher Mary Colak found that the word choice in obituaries written by families was reminiscent of 19th-century language. While men’s obituaries tended to use success-related terms like “knowledgeable” and “experienced,” women’s obituaries tended to use social terms like “kind,” “generous” and “loving.”

Colak made several suggestions to ensure greater balance. She encouraged authors to avoid gender stereotypes and to remember that achievements and virtues can take many forms in both men and women.

But she also gave a tip that everyone can use: Everyone should write their own obituary in advance so that they are remembered exactly as they wish.