“My subconscious is in my garden”: Insights into Jamaica Kincaid’s new book

Cover imageJamaica KincaidPhotography by Kenneth Noland

Jamaica Kincaid‘s attachment to the garden in adult life, as she writes in the introduction to her 1999 collection of essays My Garden (Book), began on her second Mother’s Day, when her then-husband, composer Allen Shawn, gave her a hoe, a rake, a spade, a fork, and some flower seeds. But true to one of the biggest themes of Kincaid’s work, this affection could also be attributed to her own mother, who grew an extensive collection of plants near Kincaid’s childhood home in Antigua. One day, one of these trees became infested with ants, so much so that the ants began to spread into the family home next door. “So she decided to burn down the soursop tree,” Kincaid tells AnOther via video call from her study in the Vermont house where she has lived for decades. “She was godlike in her destructive power.”

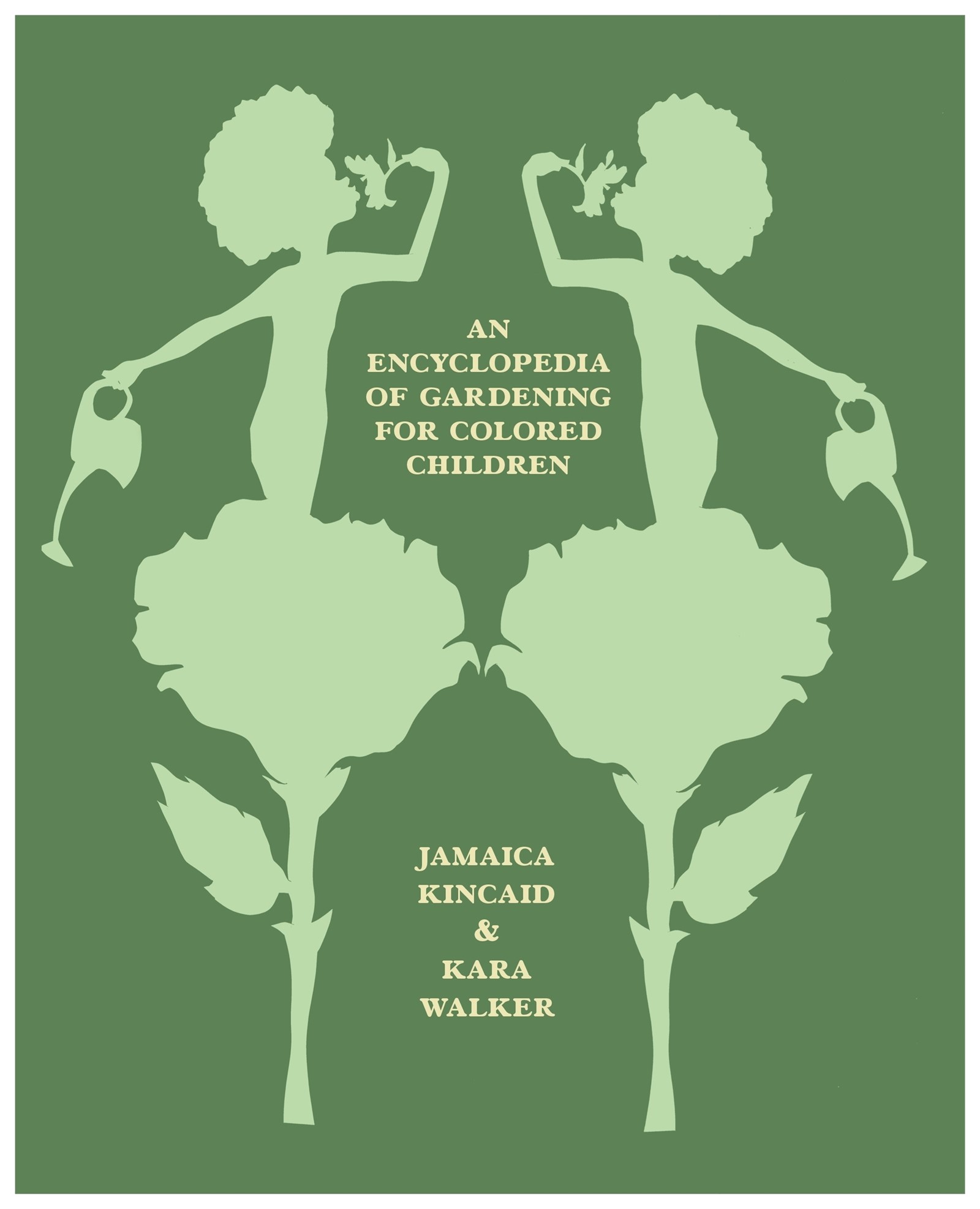

We discuss Kincaid’s latest book, An encyclopedia of gardening for children of color, was created in collaboration with visual artist Kara Walker. “I think of it as Kara’s book, the illustrations are so beautiful,” she says. Although it’s billed as a children’s book that’s really for everyone, Kincaid uses the letters of the alphabet to explore her decades-long fascination with the garden; how it’s connected to memory, its paradisiacal qualities, and the ambivalent legacy of colonialism in the plant world.

Kincaid, a groundbreaking, even mythical figure, began writing for The Village Voice And The New Yorker in the 1970s and later wrote numerous books, including the novels Lucy And Annie Johnand the non-fiction book My brother. In conversation, she is very funny (“I could make you laugh all day”) and dispenses prophetic wisdom as casually as her one-liners. While writing this interview, I found myself making a list of the lines I don’t include. Although it wasn’t customary, it didn’t feel right to leave them out. Read the List at the end of the interview.

Below, Jamaica Kincaid talks about working with Kara Walker, the connection between gardening and writing, and her stylish youth.

Holly Connolly: Tell me how this book came about.

Jamaica Kincaid: I read an article that said there weren’t really many books for children of color, and I thought, “What color can children be that there are books for them?” The article was saying that the books are only for white children, but white is a color too. I knew what they meant, but I thought, “That’s a stupid way of saying it.” So I thought I’m writing a book for children, but I’m playing with the concept of “children of color.” The truth is that the book that Kara (Walker) and I ended up writing is for children all over the world, and for everyone, really. I really can’t write a children’s book.

HC: Did you know Kara Walker before you worked together here?

JK: No, I didn’t know her. We had been in the same room but had never spoken or introduced ourselves. But I thought of her and knew that (writer) Hilton Als knew her, so I called him and said, “Can you introduce me to Kara?” And then she and I started working together, even though we still hadn’t met. I sent the writing and she sent drawings back.

HC: I see a lot of parallels between your works. How was it working with her?

JK: I didn’t realize that my thoughts about things were actually a conversation I was having with her. I wasn’t aware of that, or I wasn’t aware of what to say. So it all came together beautifully. There was nothing I could say that she would say, “Oh, I don’t know what you mean.” No, she was just totally into it.

HC: You wrote about gardening: “Nothing works as I imagined it would, nothing looks as I imagined it would, and when sometimes it does look as I imagined it (and thankfully that is rarely the case), I am surprised that my imagination is so ordinary.” I think that could also be a description of writing. Do you see a relationship between writing and gardening?

JK: When I’m in the garden, I write. I think I have a strange relationship with the garden. Often things appear that I didn’t plant. It’s like someone comes and plants something when I’m not looking.

HC: It’s very similar to writing, isn’t it? Sometimes after you’ve written something you realise there’s something in there that you didn’t intend. Maybe like a part of your subconscious.

JK: Exactly. I’ll tell you how my subconscious works in my garden. Many of the plants I grow in my garden are bigger than the literature suggests. My friends come into my garden and say, “Oh! My plants aren’t that big.” I think there’s something between the garden and the gardener, and certainly there’s something between me and the garden. I didn’t expect it. But we humans naturally tend to think that we’re the only other living things that matter. Maybe that’s why we destroy each other so much.

I’m not surprised when someone says, “Trees communicate.” Of course they do. Everything has something in it. There’s nothing that’s ever really dead; it’s not dead, it’s just not what it was before you killed it. That’s how I feel about the garden. So I get philosophical, I think about things like that when I’m in the garden, and then I go in and write.

HC: The D in the encyclopedia stands for daffodils. I was thinking of your 1990 novel Lucy, and Lucy’s hatred of daffodils as a kind of symbol of colonialism.

JK: The Colonial Office designed our education – Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, we all had more or less the same education – and we were supposed to read (William) Wordsworth and learn the poem by heart I wandered lonely like a cloud. I had a very political mother, so it’s not surprising that I noticed, but I noticed that we didn’t have any daffodils. We would never have any, and I resented that.

When I came to America, I realized that we would be reciting with all our hearts and sincerity a poem that was not ours. And so I hated Wordsworth. But then I came to the conclusion that that wasn’t Wordsworth’s fault and that the poem is beautiful. So now I honor Wordsworth by planting daffodils. At the end of the season last December, it was warm and they were selling 1,000 daffodil bulbs for $260. I bought 2,000 and planted them in the lawn in a pattern so they look like a river flowing into a larger sea.

“The truth is that the book that Kara (Walker) and I ended up making is for children all over the world and really for everyone. I really can’t write a children’s book” – Jamaica Kincaid

HC: As is well known, you had a very style-conscious youth.

JK: I had blonde hair, shaved my head and eyebrows, and wore unusual clothes. Until recently, I never really questioned what I was doing. It just seemed like a wonderful thing to do, so I did it.

HC: And that was around the time you started working for The New Yorker. Did you want to change your appearance when you began to develop your identity as a writer?

JK: I think so. Well, I didn’t want people back home to know I was writing because I was sure I would fail, but that didn’t stop me from doing it. The truth is that the person who was writing and the person I used to be didn’t fit together.

HC: You were sure you would fail, but you did it anyway. Why? What do you think that impulse is?

JK: I don’t know. It’s true though. It’s not that I’m not afraid of failure, I don’t like it at all. But I don’t want to say I’m brave or anything, but I just think, “Let’s see.” And I find that a lot of people around me don’t have that idea.

An encyclopedia of gardening for children of color by Jamaica Kincaid and Kara Walker is published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and is available now.

About wealth

“It’s really a plea against money. The people who are rich are terrible examples and so miserable. On the other hand, it’s so miserable when you don’t have any money and you wish you had it.”

On what we might consider divine retribution

“You never do anything, and I’m not talking about karma here, but it’s just a law of nature, you never do anything that you get away with.”

About Jean Rhys

“She is the mother of us all.”

Turn on

“When I see a power dynamic developing that gives me an advantage, I make a conscious effort to back off. Why is that? Because I know what it’s like to have something like that directed against me. I don’t like the way it makes me look. It’s not about how I feel, it’s about how I look.”

On her relationship to contemporary fashion

“A lot of young people wear socks today. I’ve been wearing socks since I was twenty because I never liked tights. And I hope they don’t think I’m trying to pretend to be young.”

On the state of the world

“We just have to get through this. I thought that in the last century, roughly now, in the ’20s, things started to get bad.”

Related Posts

Operation Love Bigger donates to Boxes of Hope | News, Sports, Jobs

All the famous faces who turned up at Taylor Swift’s Dublin concerts as fans celebrate ‘sensational’ weekend