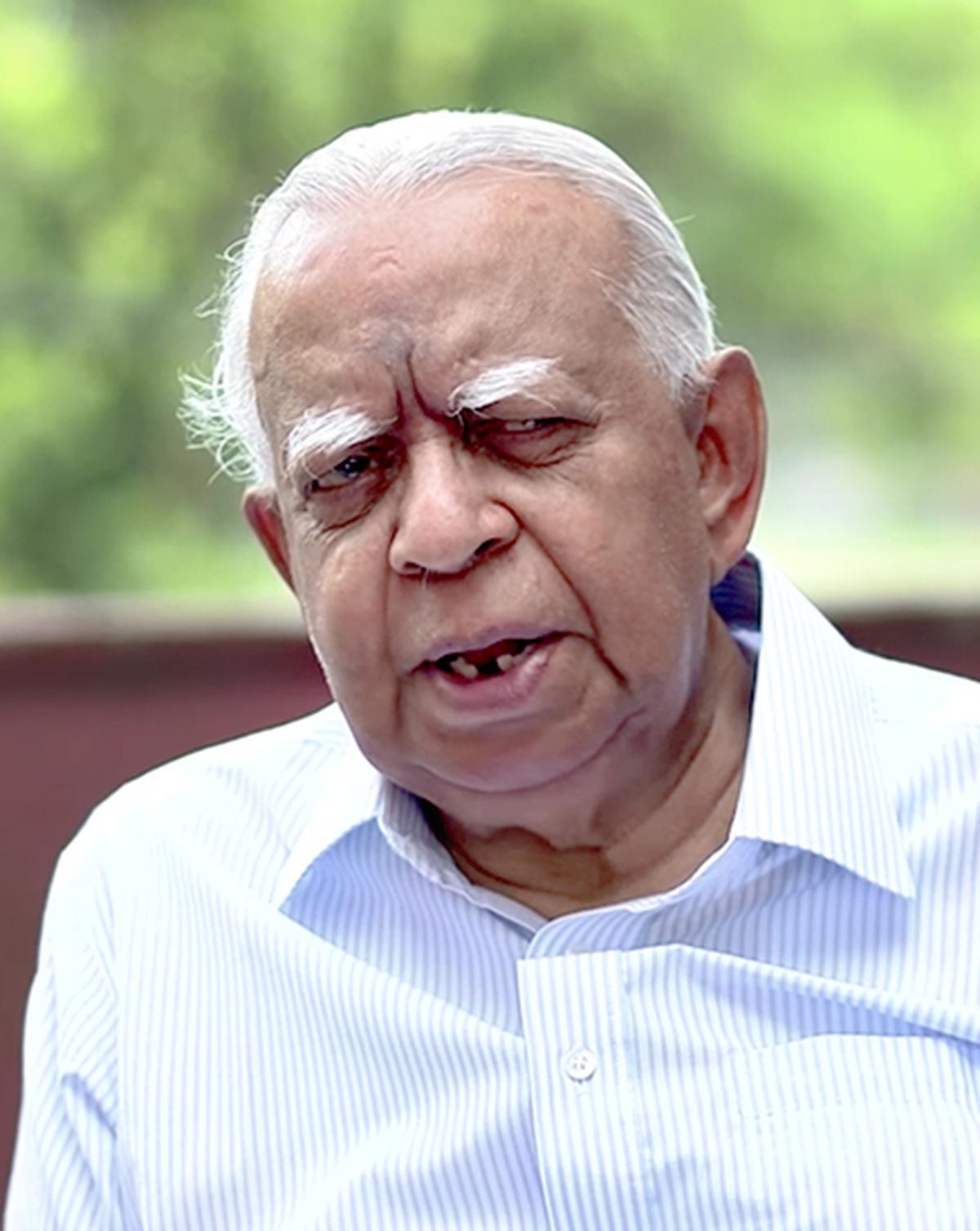

TThe recent death of R. Sampanthan, a veteran leader of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) in Sri Lanka, has left a vacuum in the political leadership of the Tamils, who have still not overcome the trauma of the civil war that ended 15 years ago. Although Sampanthan was unable to make much progress in resolving the Tamil question, he was seen as a stabilizing force, especially in the years following the civil war. He negotiated with everyone, including the Sinhalese leadership.

Leader of the Tamils

Sampanthan was a follower of SJV Chelvanayakam, who founded the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Katchi (ITAK) in 1949. He was elected to the Sri Lankan parliament for the first time in 1977, as one of the 17 MPs of the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF), of which ITAK was a part. This coalition won the parliamentary elections in Tamil constituencies with the aim of a separate state. The anti-Tamil pogrom of 1983 led to an exodus of Tamils to India, which dragged New Delhi into the ethnic issue. The nature of India’s involvement changed when Rajiv Gandhi replaced his mother Indira Gandhi as prime minister after her assassination in 1984.

Sampanthan witnessed the change in the Indian government’s dealings with the TULF. The coalition was previously the sole representative of the Tamils, but became one of their representatives, as demonstrated by the 1985 Thimpu talks held to find a solution within the framework of the Sri Lankan constitution. Later, the Indian government began to work more closely with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). When the Rajiv-Jayawardene Accord was signed in July 1987, the LTTE was not yet a signatory, but India’s talks mainly revolved around the Tigers. This approach displeased the TULF, including Sampanthan. The 13th Amendment, which provided for the establishment of provincial councils with limited autonomy across the island, was a major outcome of the agreement, but met with a lukewarm response from Tamil leaders. Between 1985 and 2000, the LTTE killed several scholars and moderate leaders such as Neelan Tiruchelvam and A. Amirthalingam.

By the 2000s, Sampanthan was one of the few remaining Tamil leaders, and his prominence was growing. Due to his pragmatism, Sampanthan, who was once said to have been on the LTTE’s “hit list”, began to adopt a pro-LTTE stance and supported the Tigers’ “freedom struggle” in the 2001 general elections. The Tamil National Alliance (TNA), of which the TULF was a member, was formed in 2001. It nominated the LTTE, which it described as the “sole representative” of the Tamils, to negotiate with the Sri Lankan government. Not surprisingly, the TULF, which had won five seats in the 2000 general elections, won 15 seats in 2001. Then the United National Party won 109 seats and Ranil Wickremesinghe became Prime Minister. The following year, his regime signed an agreement with the LTTE with the mediation of Norway.

After the LTTE’s defeat in May 2009, Sampanthan led the TNA prudently, avoiding an extreme or confrontational approach. There have been instances when the TNA has disagreed with the government of the day – such as when it refused to join the All Party Representative Committee in 2009 to reach a political solution. However, over the past 15 years, the TNA has not boycotted any major elections. In 2013, it won the Northern Provincial Council election, although the performance of Sampanthan-selected Chief Minister CV Wigneswaran (2013–2018) proved to be a disappointment. In the 2010 and 2015 presidential elections, the TNA supported the opposition candidates – General (ret.) Sarath Fonseka, who played a major role in the LTTE’s defeat, and Maithripala Sirisena, who had served as defence and health minister in Mahinda Rajapaksa’s cabinet. When Sirisena shocked the world by defeating Rajapaksa, TNA support was cited as the main reason.

Economic reconstruction

After the civil war, the Sampanthan camp focused on accountability, truth, justice and a lasting political solution for the Tamils rather than on the economic reconstruction of the war-affected Northern and Eastern provinces. They also pursued the unattainable goals of federalism and self-determination. Before he resigned as President in January 2015, Mr. Rajapaksa oversaw the reconstruction of basic infrastructure in the affected areas. Much more needs to be done but unfortunately this has not been a priority for the Sampanthan camp. With the elite of Tamil society settled in the West and elsewhere, the politically and economically weak sections are unable to negotiate with the Sinhala leadership for greater devolution of power. Tamil youth living in the North and East prefer to work as unskilled labourers and further their studies elsewhere in the world. Unless the North and East become economically strong, the situation will remain the same.

When Sampanthan died, he was apparently isolated within his political formation. Like him, Sri Lanka’s Tamils have also been cut off from society. This is largely due to the unwillingness of the Sinhala political leadership to accommodate their aspirations. It is high time that Tamil politicians worked to create more space in the economy for Tamils and encourage the youth to pursue higher studies. India, which has a moral responsibility towards Tamils, should support any endeavour that improves the community’s economic status in “united, undivided, indivisible” Sri Lanka, as Sampanthan said.

This is a premium article available exclusively to our subscribers. You can read over 250 such premium articles every month.

You have reached your limit for free articles. Please support quality journalism.

You have reached your limit for free articles. Please support quality journalism.

You have read {{data.cm.views}} out of {{data.cm.maxViews}} free articles.

This is your last free item.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x214:751x216)/Idaho-murders-book-Howard-Blum-062024-tout-24e2cbd88f93469a879533c1a665c5f0.jpg)