Read this interview with Fred Waitzkin

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to an abstract artist mother and a lighting salesman father, Fred Waitzkin knew he was going to be a writer by the age of 13. He had tried other things, including sales, deep-sea fishing, and being an Afro-Cuban drummer, but given the literary influences of his parents and Ernest Hemingway, it made almost no sense for him to become anything else.

Waitzkin studied English at Kenyon College, earned his master’s degree from NYU, and then taught poetry at the College of the Virgin Islands, where he met his wife, Bonnie. After the two settled in New York City, he tried unsuccessfully to write short stories and eventually began his career writing feature stories, personal essays, and reviews for various magazines.

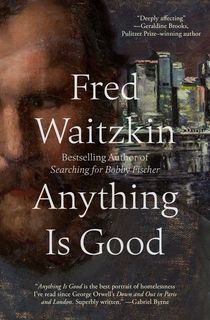

He published In search of Bobby Fischerone of his best known works, in 1984, and has been publishing books ever since. His latest novel, All is wellis a complex and ingenious portrayal of homelessness, inspired by Fred’s childhood friend. Waitzkin talks more about it in our interview with him below.

1. What inspired your latest novel? All is well?

When I finish writing a book, I usually feel an emptiness that is hard to shake off, and I worry that I will never find another subject that fully captivates me. I have fleeting ideas in my head, but none of them are something I want to put into a book.

Three years ago, that feeling was heightened when I had recently lost my two closest friends. In that time of darkness and loneliness, I began to think of my best friend from high school, Ralph Silverman. Ralph was the smartest kid in our high school and made a name for himself as a brilliant philosopher right out of college.

I didn’t even know if Ralph was still alive, but I knew he had lived in a tiny apartment in Fort Lauderdale. One day I called him and was relieved to hear his voice and the same throaty laugh I knew so well from 65 years ago, when we were bad boys, skipping school together and going to jazz clubs on the weekends in secret.

I asked him to tell me about the years he seemed to disappear from the scene. In the months that followed, Ralph told me in numerous phone calls one of the most amazing stories I had ever heard. It was the inspiration for my new novel: All is well.

2. You have named Ernest Hemingway and both your parents as strong literary influences. How have they influenced your writing?

My parents should never have married. In the sixteen years they were together, I never witnessed a single moment of tenderness between them. My mother was an abstract painter, a lover of progressive jazz, a renegade forced to live in Great Neck, Long Island, among people she could not relate to.

Dad was a salesman, and an exceptionally talented one at that. He sold commercial lighting fixtures for office buildings in Manhattan and earned a reputation in the 1960s as a tough negotiator who would do whatever it took to close a deal.

I idolized my father, who took me fishing on weekends and often made his biggest light deals in fancy nightclubs. Sometimes I went with Dad to Embers, where George Shearing played his magic piano and Armando Peraza pounded the conga drums while Dad made his deals. I wondered if I could be like Dad someday, going to nightclubs, smoking Luckies and making big deals.

But it was Mom who introduced me Hemingwayset Life Magazine in front of me and ordered me to read his story about an old man wrestling a 2,000-pound marlin. Hemingway’s sentences had a rhythm that swept me along in the same way that Armando Peraza’s rhythms seemed to seal the lightning bolt in Abe as we walked to the Embers. Over the years, I learned from my parents’ conflicting sensibilities the tension needed to develop compelling plots, and to this day I write my sentences to the beat of the drums.

3. Because of the film adaptation, you are probably best known for your first book, In search of Bobby Fischer. What motivated you to document your son’s story in this way?

Forty years ago, I was writing articles for magazines. In an article for New York Magazine, I wrote about park chess crooks who worked late into the night in Washington Square Park. Some of these guys were high-level tournament players who wanted to make easy money by making chess moves. Shortly after the story appeared, I was contacted by an editor at Random House, Joe Fox.

The afternoon I visited Joe, I was nervous as hell. I had never written a book before and Joe Fox was Philip Roth’s And Ralph Ellison’s Editor. Joe and I had a nice conversation, but he didn’t seem really interested in a book about chess hustlers. Then he asked me why I was so interested in chess, and I told him that my six-year-old son Josh was crazy about the game and often played against the hustlers in Washington Square Park and sometimes could argue that my little boy was a much better player than me.

Then Joe said to me, “This is your book.” I swallowed and nodded, but I actually thought he was crazy. Josh was just a little kid. How could I write an entire book about a little kid? What if he stopped playing chess in a few months? What would happen to the advance Random House paid me? This idea seemed like a terrible mistake, but that’s how the idea of In search of Bobby Fischer was born.

4. Your first books were non-fiction, but for the last 11 years you have published novels—The Dream Merchant, Deep Water Blues, Strange Loveand now All is well. What prompted this change? Can you imagine returning to the world of non-fiction?

After graduating and spending a few years teaching literature at the College of the Virgin Islands on St. Thomas, I felt ready to write my first novel. My mother had a run-down studio with cold water in the 14th floor.th Street across from S. Klein. She lent it to me so I could write my first novel.

I worked there for a year, often with Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane music blasting from my hi-fi, while I tried to discover the original storyline that would make me famous. I wanted to write something like Anna Karenina. I tried all year, but never wrote a decent page. I couldn’t think of a single original plot. It was devastating. How could I be a novelist without a decent plot?

After that, I started writing articles for national magazines on a freelance basis. I wrote about writers, sportsmen, adventure stories and personal essays. I always wrote my stories in the first person, which was unusual at the time, but my editors seemed to like my quirky point of view.

Through writing first-person nonfiction, where my point of view was always an element of my story, I was introduced to fiction. Eventually I realized that many, if not most, of the novels I admired were based on true stories.

Hemingway’s the old Man and the Sea was based on a true event in Cuba that Hemingway had written about in a magazine article fifteen years before writing the novel. Jack Kerouac’s novels could also have been called memoirs, since they were based on stories that had happened in his life with his friends.

Realizing that my own “true” stories were a gateway to fiction opened the world of fiction to me. Where there had been no stories before, I could now imagine many – many that I had experienced myself.

Okay, it’s not that simple. I had to find the right story for Fred, one that I could expand on and take to a new place, and one whose plot would interest or captivate readers.

Will I ever write non-fiction again? That’s a difficult question. When I start telling a story from my life to my family, my son and daughter immediately start laughing. Then one of them says, “That never happened, Dad.” They always accuse me of making things up.

5. What is the last book you read that you wanted to tell the world about?

Somehow over the years I have never read Graham Greene, which amazes me today and perhaps says something about changeability. About a month ago, on the advice of a friend, I started reading Greene, and today I feel like I never want to stop. I have read four of his books, and one of them, The Quiet American3 times.

He is an absolutely brilliant writer, on the level of Hemingway or Faulkner, and yet, seventy years after he wrote his masterpieces, he is rarely read and largely forgotten. My favorite is The Quiet American. Love and war have always been fertile ground for fiction, and in Greene’s novel, the tender and largely pre-verbal love affair between Fowler, an elderly, cynical, opium-addicted journalist, and Phuong, a twenty-year-old Vietnamese dancer, is a contrast to the gruesome violence of the early days of the Vietnam War.

All is well

Despite Ralph Silverman’s genius, he was an easy target for bullies because he studied philosophy, enthusiastically watched foreign films, produced music on the computer, and had long conversations with his parrot. And unfortunately, his adult life was not much different.

Despite being friends with great scholars and being the son of a wealthy (if shady) businessman, Ralph ends up in South Florida, where he is physically abused and thrown into homelessness with nothing more than a pair of broken glasses. All is well is the story of a man tormented by the fate of his childhood friend and the tale of how that friend overcomes the ups and downs of homelessness.