Why did the miners go on strike in 1984? 40th anniversary of the historic industrial action

On the occasion of the 40th anniversary of this historic event, “heartbreaking” testimonies about the miners’ strike are presented.

This month marks four decades since strikes broke out when tens of thousands of miners protested against plans by Margaret Thatcher and her Conservative government to cut 20,000 jobs and close numerous mines.

The miners’ strikes, the largest wave of industrial action in the country since the war, are considered to be momentous but also divisive in British history.

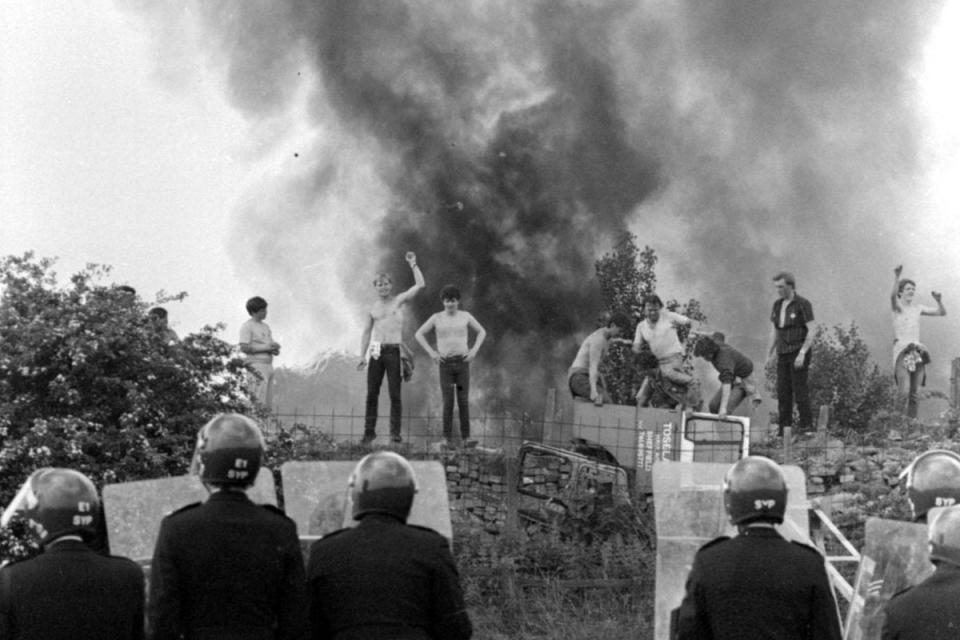

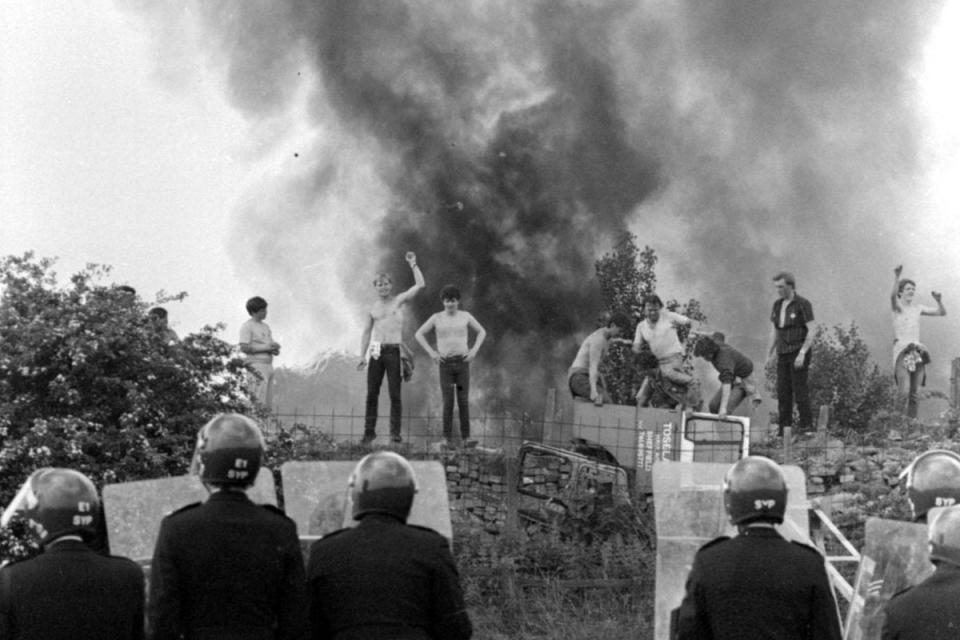

The strikes tore apart entire communities and led to violent clashes between miners and police officers deployed to monitor the protest marches.

People lost their livelihoods and the strike slogan “Close a mine, kill a community” eventually became a reality in many mining towns.

As with many civil claims in the United Kingdom, the consequences of the miners’ strike hit the local people hardest.

In 2023, British politicians called for the pardon of miners convicted during the strikes. However, some unresolved tensions remain between the affected communities to this day.

What were the causes of the miners’ strike in 1984?

In early 1984, the British government confirmed plans to close 20 coal mines, putting thousands of jobs at risk, particularly in northern England, Scotland and Wales.

However, rumours suggested that up to 70 mines were actually facing closure at the time, which caused great concern among the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM).

Previous strikes in the 1970s had caused significant disruption across Britain and the government had built up coal stockpiles in anticipation of further strikes.

In the days following the government’s announcement, miners in coalfields in various parts of the country decided to go on strike.

A strike at Cortonwood coal in Yorkshire on 5 March is often regarded as the first miners’ strike. Other coal mines quickly followed suit and the NUM called an official strike on 12 March.

With their livelihoods and the wellbeing of their families at risk, most miners took part in the strike, walked out of their pits and joined large protests across the UK. Thousands took to the picket line, demanding that the closures be stopped in solidarity with their colleagues.

Thousands of police officers, many from mining areas, were ordered to monitor picket lines – which sometimes led to violence.

Thousands of people were prosecuted for incidents related to the miners’ strike. Many of them were unable to return to work after the charges were brought.

This strike lasted about a year, resulting in many people not receiving wages and struggling to feed their families while fighting to save their jobs.

However, not everyone agreed with the strike. Many miners in Nottinghamshire continued to work. Others, who were struggling to make ends meet, returned to work early.

These miners were often called “strikebreakers” and ostracized by their community because they continued to work. Britain hoped that by dividing the strikers, they could end the protest.

With thousands of miners still working and Thatcher still hoarding coal stocks, the strike did not have the desired effect.

How did the miners’ strike end?

On March 5, 1985, after days of heated discussions among union leaders, the miners officially returned to work. Many of them experienced this return with mixed feelings, including a sense of defeat and betrayal by those who had continued to work during the strike.

However, the consequences of the miners’ strike had only just begun.

In the years that followed, the government gradually closed several coal mines across the country. This ultimately marked the beginning of the deindustrialisation of Britain, with profound consequences for working-class neighbourhoods.

There was also a mass privatization of national industry and the strength of trade unions and workers’ rights declined.

Strikes continued in the following years, but they had little effect and practically meant the end of the British mining industry.

In many working-class districts of former mining towns, the effects of the events of 40 years ago are still felt.

Why were British coal mines closed?

The British coal industry has a long history of strikes, but the market has increasingly been viewed as unprofitable.

New technologies, competition with foreign mines and increasing acceptance of the negative environmental impacts of mining probably also played a role.

But rather than gradually dismantling and replacing industries, Thatcher’s decision to close the mines altogether seemed to serve a different purpose.

Some believe that the dismantling of unions like the NUM was an attempt to push for further privatisation, reduce the level of government subsidies and at the same time weaken workers’ rights.

During Thatcher’s time in office, 115 coal mines were closed in Britain, and under John Major the number was 55.

How many coal mines are still open in the UK?

There are no more opencast coal mines in operation in the UK. Ffos-y-Fran, the country’s last opencast mine, is scheduled to close in November 2023.

However, there are still several other mines in operation.

According to UK government statistics, there were six underground coal mines in operation in March 2023.

Aberpergwm Colliery, an underground mine in Wales, is currently facing legal challenges related to attempts to expand mining operations.

In December 2022, the Conservative government approved the first coal mining project in decades, the Woodhouse Colliery. Although the project was expected to create a number of jobs, environmental groups criticised it for not prioritising the UK’s commitment to reducing emissions.