Austin African American Book Festival Offers Revolutionary Youth Program: 18th Annual AAABF Offers Youth Opportunities for Expression – Events

Courtesy of the Austin African American Book Festival

Now in its 18th year, the Austin African American Book Festival is a showcase for the eloquence of black culture.

From arts-focused programs to compelling conversations with some of the world’s most renowned authors to targeted educational outreach to the city’s youth, the AAABF exemplifies the power of Black literature. Reading is an act of revolution, harking back to a time when even learning to read was often a deadly offense for Black people. Turning to literature and diving into worlds beyond our wildest dreams is also an act of freedom. In the month that marks the end of pre-Reconstruction-era slavery, festivals like this are more than just a good time (which, of course, is absolutely true). The AAABF is a celebration of the freedom of our collective spirit. While fitting, it’s a miracle and an act of grace that admission to the event is completely free.

Black feeling, black talk

Both the theme and the general energy of Saturday’s edition of this history-making event made it a day that often reawakened dormant revolutionary stirrings. Those who were able to attend the main festivities were able to reconcile their understanding of what it means to be both an artist and an activist. It is fitting, then, that one of the main stars of this year’s AAABF came in the form of Nikki Giovanni. The poet and activist blesses every space she blocks, speaking from a wealth of experience as deep as her heart for change. With that in mind, she spoke about the very nature of this year’s theme: Black people talking about black feelings. In a now-famous conversation with the late wordsmith and activist James Baldwin, she discusses love in the context of a man coming home to his wife and children. She says in particular: “Because I love you, I get the least from you.” Like the study of the written word, love is an act of revolution because “it is like anger. You don’t fall in love,” says Giovanni, “you learn to love. And you learn the patience of love. That’s what Jimmy,” she calls Baldwin with the affection of a sister, “and I talked about. ‘What is love?'”

Poet and activist Nikki Giovanni: “Love is revolutionary because it is like anger.” (Courtesy of Austin African American Book Festival)

As she goes through the intricacies of the famous conversation, Giovanni mentions another literary (stage) star, August Wilson and his play fences. It’s the idea that someone (in this case, the main protagonist Troy Maxson) is looking for his “fun”, his fantasy, somewhere else because everything in his life is so tedious. Meanwhile, his wife Rose is taking care of the house and fulfilling her “marital duties”. She asks him, “Do you think this is fun?” “I love that phrase,” Giovanni says, smiling. “Do you think it’s fun to be a wife or a mistress? Do you think it’s fun to be a mother? I don’t think so. All of this is hard work, and the work we put into it must be appreciated.” Love is hard work, is anger, is revolution. The same passion, the same blood, the same pain and sacrifice that goes into being a wife, a mother, a mistress, being a man who is underpaid and undervalued, it’s the same backache and heartache that comes with revolutionary acts, with activism.

Giovanni’s presence and her devotion to literature raises another notable issue: the apparent trend toward illiteracy. One might think there is a rise in attempts to silence the masses by keeping them ignorant of the world around them. This trend is most evident in the way certain literary works are banned and educators and students are punished for their literary curiosity. But Giovanni sees the nuances in the way people engage with literature. “What do you think rap is?” she asks matter-of-factly. She reiterates the historical significance of our people when they were first taken into slavery. “We weren’t allowed to learn to read or write, so we learned to sing,” she says. “As songs evolved from spirituals to gospel to blues, we also got books and what is called freedom. But people forget that it wasn’t the black people who were enslaved; it was actually the white people because they had to learn to hate us and they had to learn to be afraid of us. We didn’t have to learn to love ourselves or learn that we were lovable. In fact, black women had no other way of looking at themselves than through the eyes of the men they loved.”

Love as a reflection. Love as confirmation. Love as revolution.

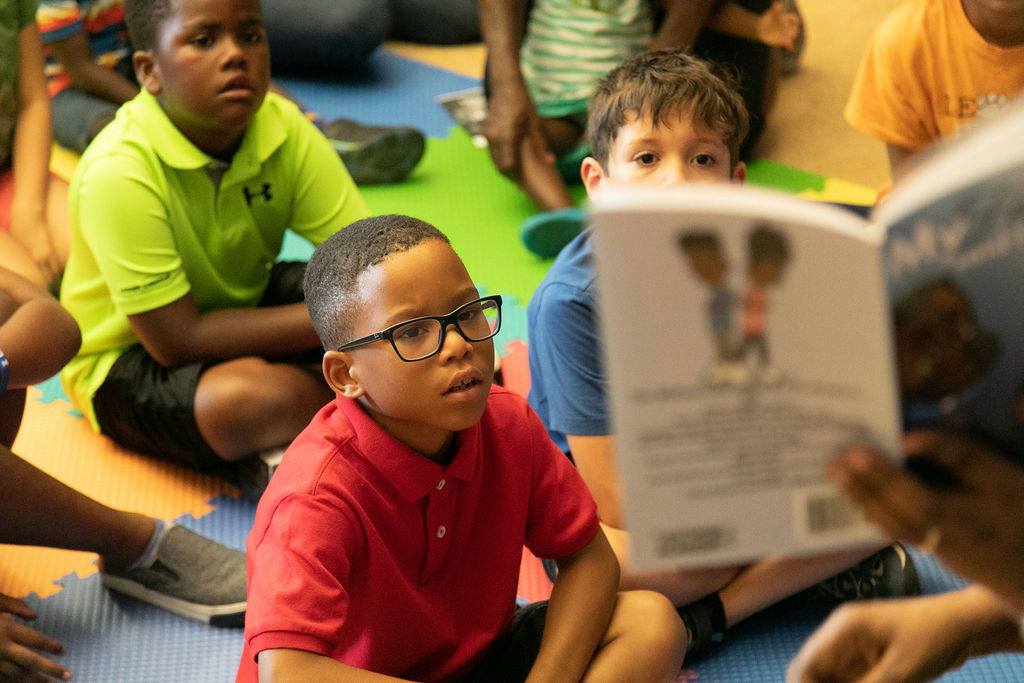

AAABF is for the children

In addition to its remarkable main event, this year the festival hosted an extensive youth program that incorporated all artistic aspects of the African diaspora – dance, collaborative storytelling, history lessons, group art sessions, etc. With an incredible lineup of writers, artists and community leaders, this year’s youth program is the essence of giving future generations the tools to fully express themselves, speak for themselves and be the harbingers of the profound change the world needs.

“Events like our festival are really about planting seeds for the future,” says Roz Oliphant-Jones, founder and organizer of the AAABF. “When young people engage with poetry and literature, it’s not just about learning to read or write. It’s about discovering their own voice and understanding the world around them through stories. By focusing on engaging young people, we give them a platform to explore their creativity, express themselves, and connect with diverse perspectives that can shape their understanding and empathy.”

“It’s also about celebrating our cultural heritage and making sure younger generations see themselves in the books they read and the stories they hear. Connecting with authors and poets who look like them and share their experiences affirms their identity and fosters pride in their heritage.”

Preserving history and culture has always been the primary goal of storytelling. From our earliest days of sitting around campfires telling tales of heroes and gods, spreading proverbs and entertaining audiences with stories of heroes great and small, literature has always been a unifying element, a means of building community. In this way, art is inextricably linked to literature. With the youth program, Oliphant-Jones testifies to the cumulative influence of art. “When you think about it, these workshops complement literature by offering alternative ways of expressing emotions and narratives. They encourage creativity and cultural enrichment. Ultimately, with the Kids Edition of the festival, we want to inspire and unite our audiences through unforgettable, multi-dimensional experiences.”

Courtesy of the Austin African American Book Festival

Ranging from dance workshops led by China Smith, founder and creative director of Ballet Afrique, to art sessions with award-winning illustrator Don Tate, to readings by authors Patrick Oliver and Terry P. Mitchell, the Kids Edition of AAABF provided many opportunities for children to engage not only with literature, but also with the creative zeal they may not always be able to express. “By expressing the emotions and themes of a poem through dance, participants can gain a deeper understanding and appreciation. This active participation makes the experience more memorable and impactful,” Oliphant-Jones says of the inclusion of a dance workshop.

This desire to offer young visitors a wide range of creative expression naturally translates to interactive ways of engaging with history. Of publisher and author Wade Hudson’s participation in this year’s festival, Oliphant-Jones says he “wants to empower young people by encouraging them to learn about and appreciate Black history.” His teaching style beautifully combines learning with history and creativity, and aims to develop a new generation of readers, writers and activists who have a strong sense of pride and purpose.

“Terry’s book The City We Built: Black Leaders of Austin is critical to preserving the history of African-American Austinites,” she says of Mitchell’s reading of her first children’s book. “It’s important for young visitors to learn about these past leaders because understanding this history helps youth appreciate past struggles and successes. It also reminds them that today’s opportunities are due to trailblazers who challenged the status quo and inspired them to aim high and make a positive contribution to their community.”

That’s what it’s ultimately about: challenging the status quo. It’s about awakening the core of curiosity and ambition in our future leaders, poets and activists. Oliphant-Jones sparked and kept alive a love of literature, but perhaps more importantly: a path to true freedom.

)