Exposing gender bias in talent shows: Insights from The Voice

Author:

(1) Anuar Assamidanov, Department of Economics, Claremont Graduate University, 150 E 10th St, Claremont, CA 91711. (E-mail: (email protected)).

Link table

Abstract

background

Data

methodology

Results

Discussion and conclusion and references

A Appendix Tables and Figures

5 Discussion and conclusion

In this article, we examine whether the gender of the coach and the artist plays a role in selecting the performance in the blind audition phase of the TV show “The Voice.” The results provide strong evidence that gender plays a role, and I show that coaches are 12 percent more likely to select artists of the opposite sex when they hear similar performances during auditions. The results are robust and account for many variations, such as coach- and artist-specific covariates. Under the interpretation of a cross-sex bias, the results would be due to male and/or female coaches being either too lenient with artists of the opposite sex, too strict with artists of their own sex, or both.

One potential mechanism by which gender interactions could lead to statistically significant gender bias could be if employers hiring in female-dominated occupations show a preference for male applicants (Weichselbaumer, 2004; Protsch, 2021). However, research by Weichselbaumer (2004) and Protsch (2021) also found that employers in male-dominated occupations preferred male applicants. However, due to data limitations, they do not account for the gender of the recruiter. Others who do not observe what I observe in my work found that employers in male-dominated occupations prefer male applicants and in female-dominated occupations prefer female applicants (Campero and Fernandez, 2018; Benard and Correll, 2010; Glick et al., 1988; Ridgeway and Correll, 2004). These works provide solid evidence of gender bias in hiring. Nevertheless, we cannot distinguish whether it is an attitude with prejudice against the other gender or one’s own gender because the gender of the decision makers is not identifiable or decisions are made collectively. In my setting, I observe the gender of the coach and the coach’s individual choice in selecting artists. Therefore, I integrate this feature of gender composition into my setting to investigate whether the coach changes his behavior based on the gender composition in the team. For example, if a coach’s team is dominated by one gender, would the coach change his behavior during the audition and select an artist of a different gender, a minority gender?

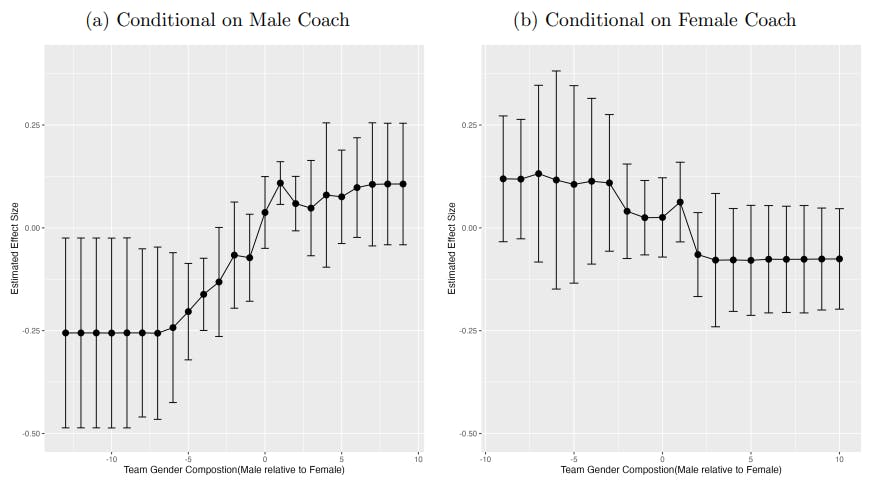

I conduct a heterogeneity analysis to assess the impact of different gender compositions in the team on the probability of selection. I took advantage of the fact that the sample I used includes both the selection of male and female coaches in the blind audition phases and whether the artist ultimately ended up on the selected coach’s team. Another advantage of the sample is that there are significant differences in gender composition in each team, including both male-dominated and female-dominated environments. Typically, we only observe one type of environment, where the company is female-dominated or male-dominated. Using these differences in gender composition, I estimate the heterogeneous effect of gender bias for male and female coaches. I found that male artists in a male-dominated team have an advantage over female artists when the coach is male. Likewise, women in a female-dominated team have an advantage over men. When the coach is female, we can observe the opposite scenarios. Female coaches tend to prefer women to men in male-dominated teams and men to women in female-dominated teams. This difference is partially statistically significant, but the magnitude remains constant.

The literature provides solid evidence for a hypothesis about group formation dynamics that are different for male and female leaders. A study of bias in other contexts suggests that men may not respond positively to the presence of gender diversity, particularly in fields where men have historically dominated. In addition, gender-related issues have been most frequently raised in groups where women are a minority or where the woman holds a leadership role (Crocker and McGraw, 1984). In addition, there is considerable evidence that women look for equality in team formation, men look for efficiency, and men perceive male or female dominance in the team to be more efficient. More directly, Kuhn and Villeval (2014) found that women respond differently to alternative rules for team formation, consistent with beneficial inequality aversion. In contrast, men are more responsive to efficiency gains associated with team production, meaning that when forming a team, men are more likely to make their selection based on who will be most efficient rather than on the criterion of gender equality. Overall, our results suggest that gender composition and the gender of the decision maker are important determinants in the hiring process. While it is difficult to say whether these findings are generalizable to other industries, they underpin the debate on gender discrimination in the hiring process.

In summary, the results provide evidence to a growing literature examining own or opposite gender bias in decision making. These findings shed light on the extent to which situational factors help to mitigate or exacerbate gender differences in the hiring process. I show strong evidence of heterogeneity in gender bias due to gender composition in the team. This evidence suggests that the selection process is primarily driven by female and male recruiters’ behavioral preferences regarding inequality or efficiency. Furthermore, the results provide a new perspective to enrich previous research on gender discrimination and shed light on cases where gender bias varies according to the gender of the decision maker and gender composition of the team.

References

Athey, Susan and Guido Imbens“Recursive partitioning for heterogeneous causal effects,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, July 2016, 113 (27), 7353–7360.

And Stefan Wager“Estimating treatment effects with causal forests: An application,” Observational Studies, 2019, 5 (2), 37–51.

Baert, Stephen, “Field experimental evidence for gender discrimination in hiring: Biased as Heckman and Siegelman predicted?”, Economics, August 2015, 9 (1).

“Discrimination in hiring: A review of (almost) all correspondence experiments since 2005,” in “Audit Studies: Behind the scenes with theory, method, and nuance,” Springer International Publishing, 2018, pp. 63–77.

Bagues, Manuel, Mauro Sylos-Labini and Natalia Zinovyeva“Does gender composition matter on scientific committees?”, American Economic Review, April 2017, 107 (4), 1207–1238.

Bagues, ManuelL F. and Berta Esteve-Volart, “Can gender parity break the glass ceiling? Evidence from a repeated randomized experiment,” Review of Economic Studies, August 2010, 77 (4), 1301–1328.

Benard, Stephen and Shelley J. Correll, “Normative Discrimination and the Motherhood Penalty”, Gender & Society, September 2010, 24 (5), 616–646.

Bertrand, M. and E. Duflo, “Field Experiments on Discrimination,” in “Handbook of Field Experiments,” Elsevier, 2017, pp. 309–393.

Blau, Francine D. and Lawrence M. Kahn, “The Gender Pay Gap: Have Women Come as Far as They Could?”, Academy of Management Perspectives, 2007, 21 (1), 7–23.

Bonander, Carl and Mikael Svensson, “Using causal forests to assess heterogeneity in cost-effectiveness analysis,” Health Economics, May 2021, 30 (8), 1818–1832.

Booth, Alison and Andrew Leigh, “Do employers discriminate based on gender? A field experiment in female-dominated occupations”, Economics Letters, May 2010, 107 (2), 236–238.

Breiman, Leo, Jerome H. Friedman, Richard A. Olshen, and Charles J. Stone, Classification and regression trees, Routledge, 1984.

Campero, Santiago and Roberto M. Fernandez, “Gender composition of labour queues and gender differences in hiring”, Social Forces, October 2018, 97 (4), 1487–1516.

Carlsson, Magnus and Stefan Eriksson, “Age discrimination in hiring decisions: Insights from a labor market field experiment,” Labour Economics, August 2019, 59, 173–183.

Crocker, Jennifer and Kathleen M. McGraw, “What’s good for the goose is not good for the gander,” American Behavioral Scientist, January 1984, 27 (3), 357–369.

Glick, Peter, Cari Zion and Cynthia Nelson, “What does gender discrimination mediate in hiring decisions?”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, August 1988, 55 (2), 178–186.

Goldin, Claudia and Cecilia Rouse, “Orchestrating impartiality: The impact of blind auditions on female musicians,” American Economic Review, September 2000, 90 (4), 715–741.

Kuhn, Peter and Marie Claire Villeval, “Are women more cooperative than men?”, The Economic Journal, April 2014, 125 (582), 115–140.

Neumark, David“Detecting discrimination in audit and correspondence studies,” Journal of Human Resources, 2012, 47 (4), 1128–1157.

“Experimental research on labor market discrimination,” Journal of Economic Literature, September 2018, 56 (3), 799–866.

Price, J. and J. Wolfers, “Racial Discrimination Among NBA Referees,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, November 2010, 125 (4), 1859–1887.

Protsch, Paula, “Recruitment contexts and employers’ hiring preferences in the German youth labor market,” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, June 2021, 73, 100608.

Ridgeway, Cecilia L. and Shelley J. Correll, “Unpacking the Gender System”, Gender & Society, August 2004, 18 (4), 510–531.

Rudman, Laurie A. and Stephanie A. Goodwin, “Gender differences in automatic group bias: Why do women like women more than men like men?”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2004, 87 (4), 494–509.

Wisselbaumer, Doris, “Is it gender or personality? The influence of gender stereotypes on discrimination in applicant selection,” Eastern Economic Journal, Spring 2004, 30 (2), 159–186.

White, Jessica“A Complete Breakdown of How The Voice Works,” https://www.nbc.com/nbc-insider/how-does-the-voice-work-everything-to-knowabout-the-format 2022. Retrieved: 09/19/2022.