Review of the anime series “Tadaima, Okaeri” – Review

There is a good chance that the particular subgenre that Tadaima, Okaeri Prefecture has frightened many viewers. The series, based on the manga of the same name by Ichi Ichikawais the so-called “Omegaverse,” a subgenre that people have strong opinions about. Based on the debunked alpha wolf theory (which assumed that wolf packs have a designated leader or alpha; the study was flawed because it looked at wolves in captivity, though that’s the short version), it’s easiest to think of it as a way for slash fiction writers to allow their favored ships to have biological children. According to the original Omegaverse lore, male Omegas can get pregnant and have children; things have since expanded so there are now heterosexual Omegaverse stories as well. (And, of course, mainstream werewolf literature that still uses the debunked alpha wolf theory, like Patricia Briggs’ Alpha and omega (A paranormal romance series.) In short, Omegaverse stories can make some people uncomfortable for a variety of reasons, not least because, like any other subgenre of romance, they can contain elements based on the “He can’t control himself!” cliche.

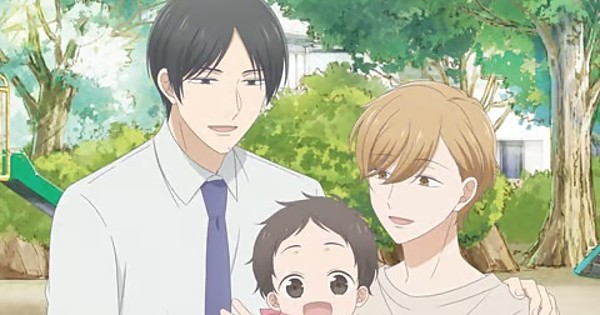

So I can’t blame anyone who watched “Omegaverse” and then decided the show wasn’t for them. It’s not a subgenre I gravitate toward, but part of the joy of reviewing media is discovering a show that exceeds your expectations. Tadaima, Okaeri Prefecture may be Omegaverse, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t also one of the sweetest true-life family stories I’ve seen in years. It also plays with the Omegaverse formula in ways we don’t usually see. Yes, people are identified by gender, sexuality, and type, meaning they’re divided into Alpha, Beta, and Omega, as is the genre norm. But while most stories in this genre take the view that Alphas and Omegas are an inevitable (if undesirable, given Omegas’ fertility) pair, this story uses the three categories as a stand-in for the kind of discrimination we see in our world. Masaki and Hiromu are discriminated against, or at least looked at askance, for being a mixed couple: Masaki is an Omega, while Hiromu is an Alpha. Their relationship and subsequent marriage resulted in Hiromu being disowned before the story even begins, and people are openly shocked and/or uncomfortable when they find out he’s married to an Omega. Masaki, meanwhile, was treated as an incredibly fragile human by his beta parents, who were shocked to have a child of a different species. He grew up with a sense of fear of himself and how the world would treat him, which left him feeling worthless.

This theme of discrimination runs quietly throughout the series. We see it in both husbands’ families – Masaki’s is more subtly upset about his marriage, as they had essentially chosen another, “safer” wife for him – but most obviously in a plot line later in the series where Hikari befriends another young boy. Hikari and Michiru meet in a park and quickly become friends when Hikari thinks Michiru’s vertebra looks like a tomato stem (this series does a great job of conveying the weirdness of young children), and Masaki also befriends the young boy’s father. They recently moved to the area after his wife died, and Mr. Mochizuki is relieved to meet another Omega. He knows Masaki is married, but he assumes Hiromu is also an Omega because that’s how things are “supposed to work,” and his late wife was also an Omega. When he discovers that Hiromu is an Alpha and Hikari is too, he panics and tries to cut off all communication, which of course means separating two toddlers who don’t understand why they’re not allowed to be friends anymore.

If you’ve experienced this kind of discrimination before, the whole thing will sound awfully familiar. Hikari was raised by two loving parents, won over his prickly grandfather, and his cheerful personality has allowed him to make friends everywhere he goes. Michiru is the best friend he’s found for himself, a person he loves, and even if he did understand the whole Alpha/Omega difference, his parents are proof that it doesn’t matter. Michiru, on the other hand, is more familiar with his father’s fear, showing what Masaki probably went through as a child; even at the age of two or three, he understands that he’s somehow different and needs to be protected. It’s not until he sees Hikari burst into tears that he starts to rebel and assert himself, seemingly for the first time. He learns that things can and should change, and that more than anything helps convey the series’ message that fear must take a back seat to love.

This may make the series sound heavy, but it isn’t; although it deals with some heavy themes, at its core it is a warm story about a family going about their daily lives. Hikari and later his little sister Hinata are big draws, and the series hits many of the same notes as Babysitter for school in the way they are portrayed. Hikari is a bundle of energy, generally cheerful, but also recognizably a toddler; he has tantrums, is scared, and definitely has an inflated sense of self. In one episode we discover him writing letters (more or less) to someone he calls his best friend, and then going off with Masaki and Hinata to deliver them; in the next scene we see him clinging to Masaki’s legs and crying in fear because the “best friend” is the golden retriever down the street, who he loves but is simultaneously terrified of. Hinata, on the other hand, has all the happy chaos of the newly mobile, making her way around and occasionally getting stuck under things. They are cute, but not to sweet, and even though they are still idealized depictions of young children, the story is still accurate enough that it is a pleasure to watch.

The biggest downside is that the production quality isn’t spectacular. The animation is often limited, and the pastel color palette can look very washed out. It’s very nice that the kids usually wear gender-neutral clothing, but all the floating pastel geometry feels like an attempt to distract from weird bodies and choppy animation. Thankfully, the voice cast can make up for these problems, particularly the voice acting of Hikari and Masaki, but this isn’t one of those shows you watch for the stellar illustrations and animation—or even the frog imagery, which is prevalent. (“Okaeri” shares a syllable with the Japanese word for “frog,” which is why we see so many of them.)

Despite the visual problems, Tadaima, Okaeri Prefecture is a show that gives you a warm hug. It’s Omegaverse, but that’s not its main attraction; Masaki could just as easily have been trans and the story would have remained basically the same. At its core, this is a show about a family that loves each other, shows it with casual physical affection, and just lives their lives together. There’s something wonderful about that, and if that sounds appealing, I urge you to put aside the genre and production values and give the series a chance.