Gail Godwin’s memoir Getting to Know Death is unusual and powerful.

When I turned 40, a friend who was about ten years younger than me asked me if I could impart any lessons to him from his then perspective of maturity. I was at a loss, and have only become more so as the years have gone by. One of the strangest things about growing older is how difficult it is to describe the experience of being older to younger people. It just seems impossible to really know what it is like to X Years under my belt without really having experienced those years. Paradoxically, this has only increased my interest in the work of old writers – just in case one of them finally made it.

In Gail Godwin’s sixth novel, published in 1982, A mother and two daughters, The author wrote a chapter in which two friends, women in their forties, hike to the top of a bare mountain and stretch out in the meadow grass and her Age. They decide that “you have to take a stand on this, that you create an image of yourself to grow into.” This crafted identity requires a “power base” that can make an old woman “the kind of witch who is feared or admired—maybe even loved” rather than ignored and belittled. The source of that power might be fame or money, or something more intangible, like becoming a “local beloved,” a small-town teacher perhaps, visited and consulted by her former students. That one chapter alone, Godwin’s editor told her at the time, was “worth the price of the book.”

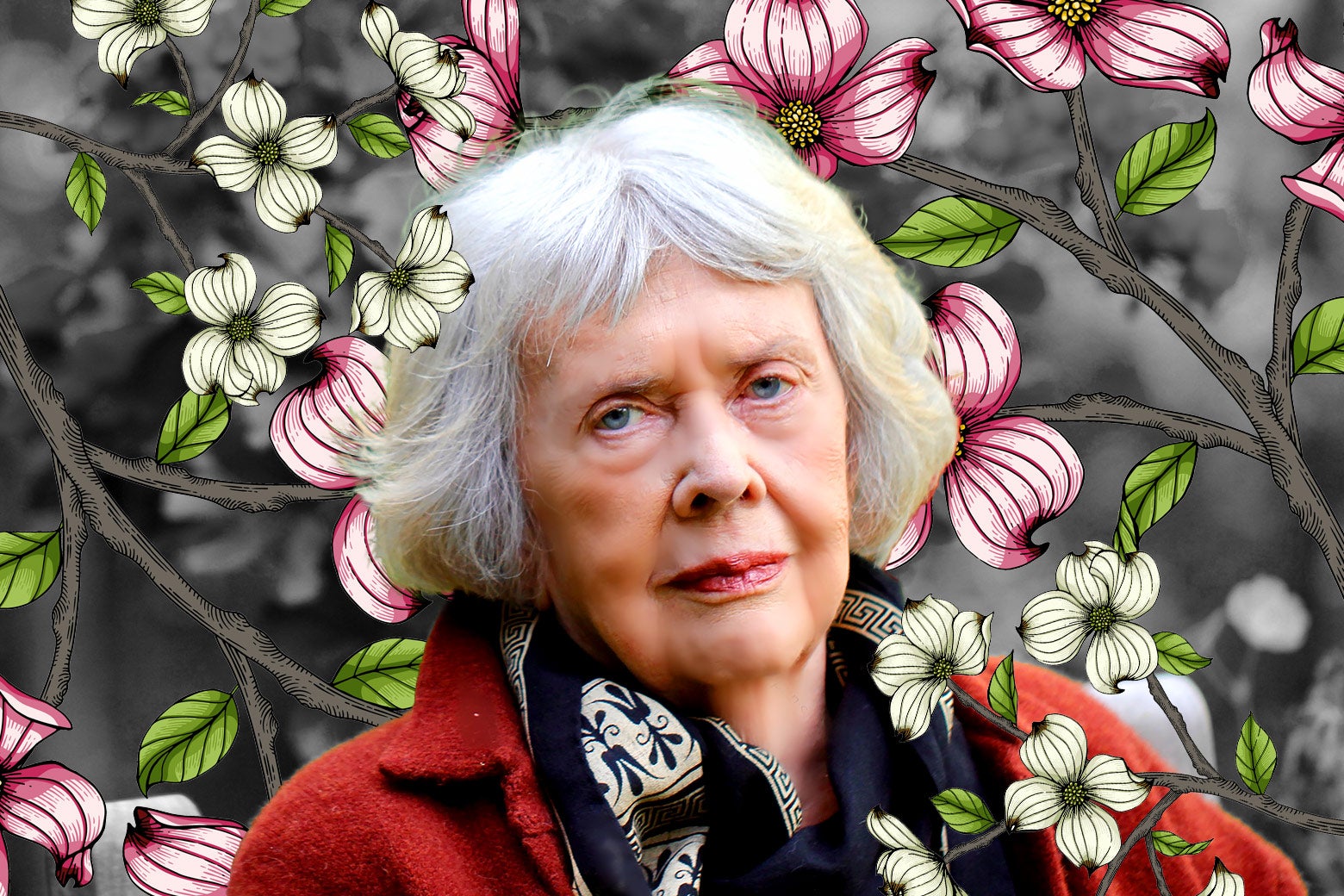

But these characters, as thoughtful as they seemed, had no idea what was in store for them. Godwin has published eleven novels in the years since these women climbed the mountain, as well as several memoirs and guides for writers. A few weeks before her 85th birthday, she is now in her first year of writing.th birthday, while trying to water a freshly planted dogwood tree on a hot day, she fell and broke her neck. She writes about the injury in her strange, fragmentary and ultimately powerful new book, Getting to know deathinitially caused only a “slightly strange” feeling in her neck. But eventually she wore a neck brace day and night for six months. Her therapist suggested that she use the time to come to terms with her mortality and gave this meditation its title.

Never in Getting to know death Godwin thinks about their “power base” or the kind of personality in which the characters A mother and two daughters so essential when you are old. One could say that this is because she managed long ago to secure the status of that rarest of creatures, namely a financially successful literary novelist. But none of this is relevant to Getting to know death, who doesn’t care at all about Godwin’s image or what others think of her. The book is sometimes very dark, sometimes funny, sometimes bright. Death is always present in the book, but it is not really confronted because its insignificance gives Godwin so little to think about. This is a little surprising because she is a Christian and presumably believes in life after death, but this book is really about the experience of being quite old and yet still retaining your creative powers.

By Gail Godwin. Bloomsbury.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items through links on this page. Thank you for your support.

Godwin’s late partner, the composer Robert Starer, who died in 2001, said of his work towards the end of his life: “I used to try to be original. Now I try to be clear and essential.” Godwin herself writes that while working on her 2013 novel Flora, She noticed that her own style was changing. “I formulated shorter, sharper sentences and approached the essential theme, which sometimes seemed almost austere.” The most exciting “experiment” for an older author, she dares to say, is the question: “How much of your story can you tell if you leave out the superfluous?”

This attitude – as Godwin surely knows – is consistent with the conventional notion of an artist’s ‘late style’: expression stripped down to its essentials, embodied by the painter JMW Turner, whose late works were initially derided but later celebrated as precursors to Impressionism and other modernist movements. Late style is often characterised as serene and accepting, although the philosopher Edward Said argued (in a book he wrote shortly before his own death from leukaemia) that the discontinuous nature of many artists’ late works expresses ‘intransigence, difficulty and contradiction’. They are the equivalent of those impatient old people who have no use for euphemisms and other niceties and who insist on calling everything as they see it.

There are some of these properties in Getting to know death. Godwin’s thoughts are a whirlwind of past (of which there is so much) and present (of which there will be a rapidly diminishing supply). Much of the book is addressed to her best friend Pat, whom she met in second grade and enjoyed for 77 years. (Pat and Gail are the models for the two friends who lie at the top of this mountain, planning their retirement together.) Pat – who gave away everything she owned except two nightgowns, moved into a Medicaid-funded nursing home, and died in 2021 – taught Godwin that “there are moral natures outside of books better than mine.” She was a constant reminder to her friend that writing and artistic ambition – the core of Godwin’s own “power base” – could only constitute a relatively small part of a dignified life.

Sometimes the demands of art can even be a hindrance. Getting to know death seems to reflect underlying reservations about the storytelling that is Godwin’s life’s work. Godwin wonders if the stories she has invested so much in are actually true. did Does 10-year-old Pat really drink defiantly from a water cooler marked “colored” in segregated North Carolina? Who was Godwin’s grandmother, really, a woman she now considers a “great mystery” and who “held more about her than I could have ever imagined.” This newfound rigor about the truth extends outward. “Be sure to fact-check websites with titles like ‘Last Words of Famous People,'” Godwin advises her reader. It turns out that Henry James did not say, “So it has come to pass at last, the noble,” when he died, but rather, “Stay with me, Alice, stay with me.”

Edward Said would insist that the non-linearity so common in the late style represents a rebellion against conventional wisdom and an acceptance of the true formlessness of life and thus a rejection of the false coherence of the narrative. It is true that the chronological meandering of Getting to know death can make it difficult to follow the text at times. The book was written in the months when Godwin felt trapped in her neck brace and was forced to move to the lower floor of her house, into the room where her ailing husband spent his last months – an ominous transition. It was certainly not possible to write sustainedly under these conditions. But the often telegraphic, even gnomic, nature of the late style seems just as likely to be the result of removing what feels like filler and throat-clearing. The essence remains. You just have to know how to read it.

Godwin’s guide in this respect is Samuel Beckett, a writer whose entire work seems like late style. I would not have associated Beckett with the psychological naturalism of Godwin’s own fiction. But she fell in love with a short Beckett text (written – yes! – in his last years), “Imagination Dead Imagine,” when she was a graduate student in her thirties. She concludes in Getting to know death the full text of a kind of prose poem she wrote under the influence of that work and published in the James Joyce Quarterly in 1971. One can understand why. It is very good, and she imagines a conversation with her younger self who wrote it, asking, “Help me try again.”

Despite it, Getting to know death is not very like Beckett; Godwin is simply not as isolated as the author of Waiting for Godot. True, the memoir is sparse and has its incantatory repetitions and fixations: how much her work borrowed from Pat’s life; her family history of suicides; the despair she felt as a high school graduate with no money for college, and the relief when her estranged father offered to pay the tuition. The little dogwood tree she tried to save — condemning herself to six months in braces, an operation and a potentially permanent disability — keeps cropping up. Yet even when she’s stuck in her living room, Godwin is no Beckett figure buried up to her neck in sand. Without her accident, Godwin would never have met people she values today, most notably her roommate at a rehabilitation center and her home caregiver. That’s what endures for her alongside writing and reading: not a power base in money, wealth or prestige, or an identity based on any of those, but the possibility of newness and discovery in the always surprising form of other people. This, at least, will never be old.