The Printed Sources of the Southern Spiritual Song

An astonishing number of human hands across continents and generations created the tradition of spiritual song in the American South. Songs and hymns featured in 19th-century revivals and church services—some of which are still known today—were created by ancient Hebrew poets, enslaved African Americans, Jacobean translators, medieval monks, 18th-century English nonconformists, shape-note transcribers, preachers, laypeople, composers, and musicians in Africa, the Caribbean, Europe, and North America. These poems and tunes were memorized, recited, sung, hummed, and whistled by people—educated and uneducated alike—on back roads, in barns, schoolrooms, fields, and around flocks in countless neighborhoods. They were printed in cities and towns on wooden and iron presses, on paper made by free and enslaved workers in factories along rivers and streams. They were then sewn together by merchants or bound into pamphlets and small books. These were sold for a few cents each by peddlers, preachers, printers, peddlers and shopkeepers on behalf of religious groups, publishers, missionary and Bible societies.

This is only a partial account of how human voices and the printed page formed a repertoire that was central to everyday life. The part of this story that is known concerns human memories and voices. What is less known to us is the importance of printers, colporteurs and readers to this tradition.

This is because Southern culture was understood primarily as an oral tradition. Accordingly, its tradition of spiritual song has been studied by a small group of musicologists and folklorists who document oral and folk traditions, rather than by historians whose natural area of expertise is the handwritten and printed page. Undoubtedly, the oral tradition was and remains crucial to the transmission and emergence of spiritual song. African-American spirituals were sung by people who wove African traditions with imagery and language from the King James Bible, and were passed along roads, across fields, and at revival meetings to black and white singers who memorized them.

But as I An educated South: Reading before emancipation (New Haven, 2019) The importance of oral tradition to the general understanding of Southern culture, as well as the misconception that printed works were not widely available in the region, has obscured the rich history of printed song in the region. No American, not even those who could not read at all, could escape the influence and presence of print in the 19th century, much as the lives of the technologically uninitiated among us are shaped by the Internet. Tens of thousands—hundreds of thousands, by some estimates—of inexpensive songs, song sheets, and pamphlets were printed and sold by dealers in the Southern states, spreading these songs not only in the region but across the Atlantic and from the southeast coast to Philadelphia and other places in the north and west.

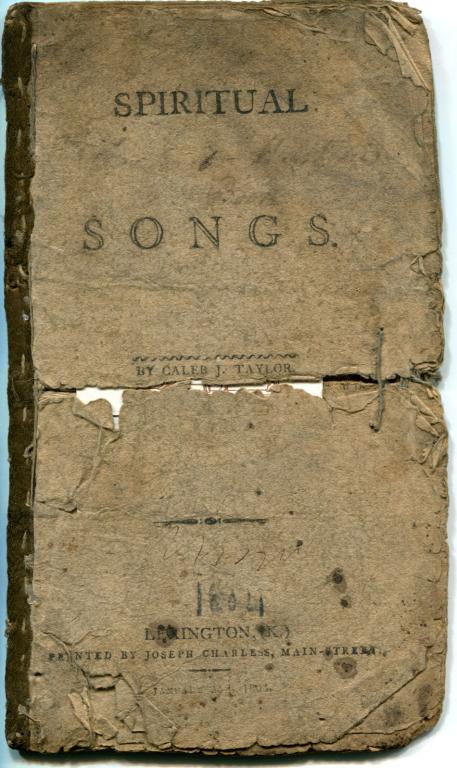

One of those forgotten objects graces the cover of my book—a pamphlet or songbook printed in 1804 under the commission of the Rev. Caleb Jarvis Taylor, a convert to Methodism who preached throughout northeastern Kentucky. “Spiritual Songs” was printed in Lexington by Joseph Charless. The title has escaped even hymnologists, but this fragile copy has somehow survived the generations, once literally torn in half before being lovingly re-stitched and deposited in the public library in Cincinnati, Ohio. I suspect it is the only surviving copy because pamphlets like these were literally ephemeral. Scholars believe that most of the output of small presses like Charless’ has not survived.

Yet ephemera can have enormous influence in their short lifespans. In the South, they transmitted songs written decades or centuries earlier and an ocean away, many of which were loved and memorized and became part of the oral tradition. One of the most surprising legacies of print was its place in the creation of African-American spirituals. The great Harvard musicologist Eileen Southern traced the influence of the first printed collection of African-American hymns, Richard Allen‘S A collection of spiritual songs and hymns selected by various authors (1801) to the first compilation of African-American spirituals, slave Songs of the United States (1867). These were collected by Northern troops and teachers on the coast of South Carolina during the Civil War, and for generations it was assumed that they came from there until Southern’s research led him to the ingenious conclusion that they were the product of independent black communities in the Philadelphia area.

Allen was the first bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and his hymn book spread along with his denomination. His congregation in Philadelphia – Bethel Church, known as “Mother Bethel” – was the most important independent black congregation in the country. The congregation’s singing of both Anglo-American hymns and spirituals was legendary. This was reflected in Allen’s book. About half of the hymns were from the Anglo-American tradition, while the rest were American spirituals. In the two decades after the hymnal’s publication, at least ten other popular compilations used by white and black singers included a large number of the texts originally selected by Allen. There was a particularly close relationship between Allen‘s book and ““The Baltimore Collection”, an anonymous compilation of the most popular songs of the time.

All‘s hymnal is a fine example of how hymns from the oral tradition found their way into print, only to return to the oral tradition. That is, favorite hymns learned by ear were printed, only to be memorized in church services and revival meetings by new singers, educated and uneducated alike. This movement from page to memory is early evidence of the wide-ranging sacred music tradition that flourished after the Civil War in genres ranging from white and black gospel to civil rights anthems to rock and roll, as my colleague Paul Harvey has documented.

The importance of printed sources to Southern sacred singing has far-reaching implications for our understanding of our history. Most of the hymnals, shape-note tunebooks, and songbooks that were so dear to Southern singers contained works from the region but were printed in Philadelphia, New York, or Cincinnati before being packaged and shipped back to the South. Publishers, authors, and booksellers sought customers wherever they could be found, in free and slave states, in the Upper South and the Upper Midwest. Books are technology and by their nature are highly portable carriers of culture without regard to the political, geographic, and social boundaries to which people so stubbornly cling. The history of sacred singing in this single region of the early United States underscores how this genre united American singers across racial, social, and geographic lines. It also shows that technology can enrich, not undermine, our society by disseminating the wonderful things that human voices and pens have created.

Today we welcome a guest post by Beth Barton Schweiger. Schweiger lives in Seattle and is the author of An educated South: Reading before emancipation (New Haven, 2019).

Related Posts

Aries Horoscope Today, July 7, 2024: Discover what the stars say about your career, finances and love | Horoscope today

Watch “icon” Kylie Kelce belt out Taylor Swift’s “Love Story.”