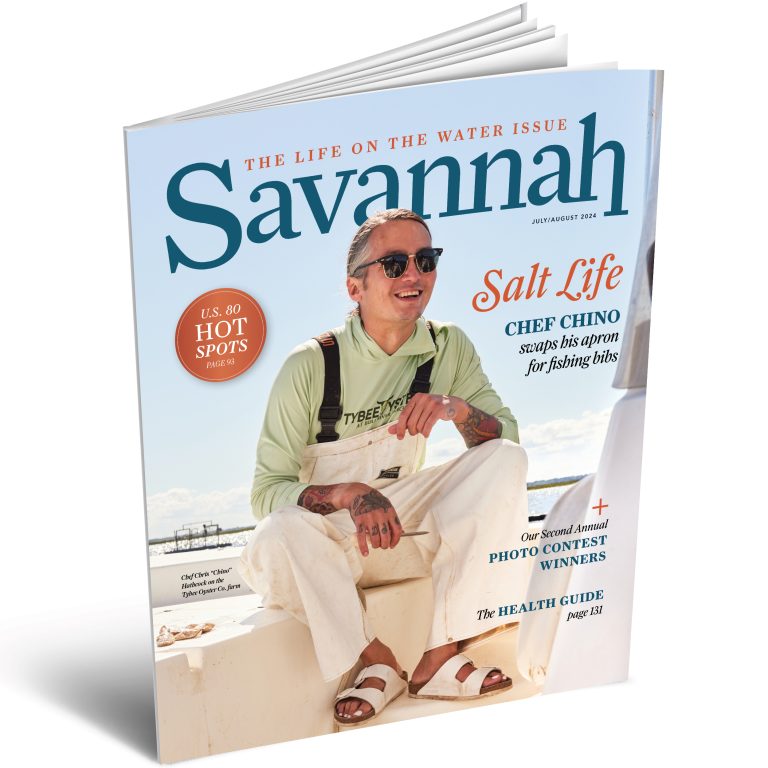

Q&A with Chef: Chris “Chino” Hathcock of Odd Gai, Shinpaku and Crybaby

Between his hip pop-ups and his rotating residency in Fleeting, Chef Chris ‘Chino’ Hathcock swaps his apron for a fishing bib while working at Bull River’s premier oyster farm.

Written by COLLEEN ANN MCNALLY

Photography by MICHAEL SCHALK

AFTER working at SOME of the Southeast’s most acclaimed restaurants, including The National in Athens, Georgia, Staplehouse in Atlanta, and most recently for six years at Husk Savannah, Chef Chris “Chino” Hathcock (also known as @chino_noir on Instagram) gave up his full-time job to have more flexible hours.

In the years since, he’s launched new original concepts, including Odd Gai, a pop-up series based on Hathcock’s travels through Thailand and Southeast Asia, and Shinpaku, an izakaya residency at the Thompson Savannah’s Fleeting restaurant. Wherever he goes, a crowd follows him, hungry to see what he’s cooking next. (Hint: It’s Mexican seafood.)

The recent change of pace also allows the Georgia native to pursue another passion: oyster farming. Before excelling in the culinary arts, Hathcock earned his bachelor’s degree in forestry and natural resources from the University of Georgia. When he’s not traveling or in the kitchen, you’ll likely find him helping oyster farmers Perry and Laura Solomon at the Tybee Oyster Company farm on the Bull River.

Here, the coastal cowboy tells us where he finds inspiration, what he loves about coastal life, and where he’s getting his food this summer.

ABOUT HIS NICKNAME THAT BECAME HIS INSTAGRAM NAME

I’m called both Chris and Chino. I always introduce myself as Chris, but everyone who meets me calls me Chino. I’ve had that nickname for over 20 years. When I was working in restaurants as a teenager, I worked with a predominantly Hispanic crowd, and they call anyone of Asian descent a Chino. They would always say “Chino, Chino” when they wanted something from me, since I was the only non-Hispanic person in the kitchen. When I moved into other kitchens, there were always two or more people named Chris – it was such a popular name in the ’80s – so Chino stuck.

ON THE EVOLUTION OF SAVANNAH’S FOOD SCENE

When I came back in 2017, there was no Starland Yard, no Fleeting, no Common Thread, no Late Air. None of that. Even in the last five years, the city has changed tremendously. It’s really good – it’s an attractive market. If you look at Charleston as a sister city, we’re very similar. We may only be a decade or 15 years behind, but the appreciation for raw ingredients is there. Savannah has definitely become a major food corridor.

(Although) it’s not changing too quickly, for me it’s definitely saturated. Any chef in Savannah would tell you it’s very difficult to staff the restaurant when new places are opening every three months. People are jumping ship for warmer climes. … After COVID, the mindset has changed. A lot of people used to glorify drudgery and work those 60- or 70-hour weeks. This time off has really helped a lot of people see things in a new light and realize there are more important things in life than drudgery and work.

SWITCHING TO POP-UPS

I worked in commercial kitchens for 20 years. That was a long time and burnout is real. I wanted to do things that were in line with my interests, work for myself and not be in the restaurant 60 or 70 hours a week and five nights until midnight. This is all about living a more balanced life, being mentally healthy and trying to have more time for the important things in life, like my partner and my dog.

I’ve been doing these pop-ups because it’s a way to continue to be creative and crafty without having to deal with all the day-to-day things that come with being a chef — labor, food costs, and all the other nuances that come with having a huge staff. … The pop-ups are just for fun and to scratch an itch. I have a very small group of people who help me creatively and cook with me, and it’s rewarding. I don’t want to do anything that messes that up. As long as it’s equitable for me and my people, as well as the host restaurant, that’s what’s important to me.

It’s still tough. You’re opening a restaurant and you’re moving in and out of someone’s space every week. You want to make sure you treat that space with respect while also operating at a high level so you’re not just doing something random, having fun and then leaving. A lot of thought and energy goes into the pop-ups and residencies.

ABOUT THE DEVELOPMENT OF ORIGINAL CONCEPTS

Odd Gai came out of Strange Bird. The name is a play on “gai,” which means chicken in Thai. So we wanted to do Southeast Asian/Northern Thai/Laotian food, inspired by where I’m from and my travels around Thailand. We also incorporated some Vietnamese food, so it really became a catch-all for Southeast Asian food—which is how I like to cook. Bright, bold, spicy flavors. Lots of acid, not a lot of fat and butter and gluten and heavy stuff.

When we did Shinpaku, it was more Japanese, with subtle, nuanced flavors and small izakaya plates. I wanted it to be as much about the saki and soju as it was about the fresh seafood and food.

How to become an oystercatcher

I’ve always been interested in oysters. I’ve always been a little bit in the thick of it – literally – supporting Southern oysters and shell recycling programs like Shell to Shore out of Athens. Over a year and a half ago, I contacted Perry and Laura Solomon and asked if I could check out the Tybee Oyster Company farm and offer them free labor – similar to when chefs work in a professional kitchen, which is like an unpaid trial. And that’s exactly what I did.

Now that they’re growing and we’ve built a relationship, we sat down and talked about me coming on board. Right now, I’m their only employee. It’s great because I grew up in and around Savannah, specifically Tybee and Wilmington. It’s very rewarding to see that oyster go from seed to marketable product and know what waters it came from and how much care went into it.

Perry and Laura are really committed to the community, to environmental education and to being stewards of the water. I can’t say enough good things about them. … There’s really no downside to oyster farming. It’s great for shoreline regeneration and habitat regeneration and water filtration and everything else. So I’m really all in.

ABOUT HIS FAVORITE WAY OF EATING OYSTERS

On the boat after we pulled them out of the water. I like them the way they are: natural.

After a few days, the salty taste slowly fades and the abductor muscle becomes saturated. They really do change every day. If I put anything on them, I only add acid – fresh lime or lemon juice.

I don’t want to do them a disservice by boiling them and putting cocktail sauce and saltines in them. The oysters you do this with are the ones you get from Oyster Creek when you truck them through the mud, pull them out during harvest time, wash them and do an oyster roast.

However, the Tybee Oyster “Salt Bombs” – as we call them – are very special. They are hand-picked from oyster baskets on the farm. You should treat them like any other heirloom product – with respect and using them as best you can. Eat them touched or processed as little as possible.

ABOUT RETURNS

The Giving Kitchen (a nonprofit that provides emergency assistance to food service workers through financial assistance and a network of community resources) is very close to my heart, as I worked for years at Staplehouse, the nonprofit’s affiliated restaurant.

The late chef Ryan Hidinger was a friend to all of us and the reason Giving Kitchen was started. Every year they host Team Hidi, a fundraiser with live auctions to raise money to support service workers in need. One of the auctions is an experience on Ossabaw Island with chefs and winemakers. I’ve been part of this for five years, so I’ve had the luxury of going to Ossabaw six or seven times now. It’s just a pristine nature reserve. You can go there just for educational, scientific or cultural purposes. It’s very special.

On our last trip we saw pigs, alligators, blue herons, armadillos, all these kinds of species. It really is a magical place. Bioluminescence right off the dock. It’s a huge, uninhabited barrier island. Anyone can go to the beach there – it’s open to the public – but you need a special permit to explore the island.

WHY HE LOVES COASTAL LIFE

It’s what the bumper stickers say: island time. It’s life on the sea. The slower pace. … I’m a Pisces, so I like being on the water, in the water, near water. I’ve lived in the mountains and I’ve lived in the city, and everything has its advantages, but Savannah is my home.

WHAT’S NEXT?

I’m working in the Fleeting Kitchen at Thompson Savannah for an extended period of time. Our plan is to do a month on and a month off for a year, focusing on a different cuisine each time. I’ll be revisiting Odd Gai and Shinpaku, but also trying out some new concepts. Starting July 1, we’re doing a concept called “Crybaby Mariscos,” or “Crybaby” for short, on Mondays and Tuesdays. It’s all about Mexican seafood, and that’s ultimately what I’m going to do for a retail space. Think aqua chilis, tostadas, ceviches—we’re sourcing all seafood from local waters and presenting it with Mexican flavors—and a tequila and mezcal program.

I’ve been doing wine nights here and there with Sobremesa and will continue to do other pop-ups as they make sense. … I’m proud that I’m doing what I love now. Not that I didn’t love what I did before, but a lot of people get carried away with the lifestyle of being a chef. It’s nice to step back, put the ego aside and do something that’s more fulfilling than being a badass chef, stroking your ego and chasing awards. I find that I have a much more fulfilling job now.

This and many more articles can be found in the July/August 2024 issue of Savannah’s Life on the Water magazine.