A home away from home | MIT News

When the Haitian Multi-Service Center opened in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood in 1978, it quickly became a valued resource. Haitian immigrants compared it to Ellis Island, Plymouth Rock, and Haiti’s own Citadel, a major fortress. Originally housed in an old Victorian convent house in St. Leo Parish, the center provided health care, adult education, counseling, immigration and employment services, and more.

Such services require significant financial resources. Soon after, Boston Cardinal Bernard Francis Law incorporated the Haitian Multi-Service Center into the Greater Boston Catholic Charities network, whose deeper pockets kept the center intact. The law required Catholic charities to promote Church doctrine. Catholic HIV/AIDS prevention programs now emphasized only abstinence, not contraception. Meanwhile, the center also began receiving state and federal funds that required recipients to promote medical “best practices” that ran counter to Church doctrine.

In short, while the center served as a beacon for the community, there were tensions over its funding and function – which in turn reflected larger tensions in our social fabric.

“These conflicts are about the role of government, where the line between public and private is – if there is a line – and who is ultimately responsible for the health and well-being of individuals, families and larger populations,” says MIT scholar Erica Caple James, who has long studied nongovernmental programs.

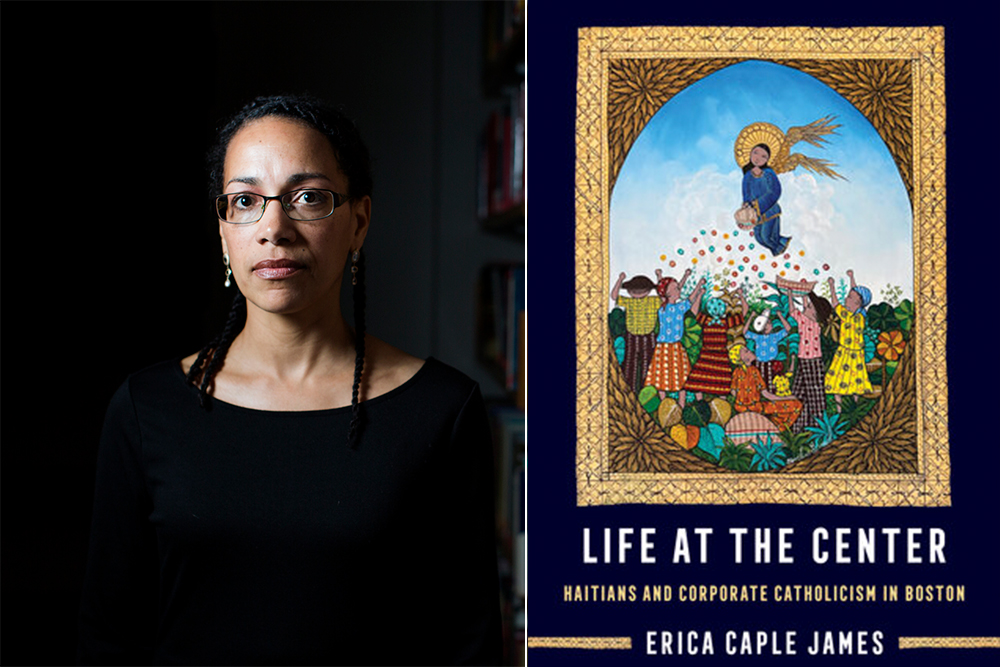

Now James has written a new book on the subject, Life at the Center: Haitians and Corporate Catholicism in Boston, published this spring by the University of California Press, which is a careful study of the Haitian Multi-Service Center that examines several issues simultaneously.

In it, James, a professor of medical anthropology and urban studies in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning, carefully examines the relationship between the Haitian community, the Catholic Church, and the state, analyzing how the church’s “pastoral power” is exercised and to whose benefit. The book also chronicles the work of the center’s staff, showing how everyday actions are tied to bigger-picture questions of power and values. And the book explores larger questions about community, belonging, and finding meaning in work and life—things that are not unique to Haitians in Boston, but are made visible in this study.

Who makes the rules?

James is a trained psychiatric anthropologist and has been studying Haiti since the 1990s. Her 2010 book, Democratic Insecurities, examined post-traumatic care programs in Haiti. James was asked to join the board of the Haitian Multi-Service Center in 2005 and remained there until 2010. She developed the new book as a study of a community in which she participated.

Over the course of several decades, Boston’s Haitian-American population has become one of the city’s most significant immigrant communities. Haitians fleeing violence and insecurity were often able to establish a foothold in the city, particularly in the Dorchester and Mattapan neighborhoods and some of the suburbs. The Haitian Multi-Service Center became a fixture in the lives of many seeking stability and prosperity. And from the clergy who lived there to those who needed emergency shelter, there were always people there to help.

As James writes, the center was “literally a home for many stakeholders and for others a home away from the home they had left behind.”

The Church’s support of the center was successful in part because many Haitians felt connected to the Church and attended services and Catholic schools. In return, the Church provided exceptionally extensive support to the Haitian-American community.

This also meant that some important issues were addressed according to church teaching. For example, the center’s education efforts on the transmission of HIV/AIDS did not address contraception because the church placed a strong emphasis on abstinence – which many staff members viewed as less effective. Some staff even went outside the center to distribute condoms to parishioners, which was not against policy.

“We started as a grassroots organization. … Now we have a church making decisions for the community,” said the former director of the center’s HIV/AIDS prevention program. In 1996, staff at the adult education center resigned in droves over political disagreements. Some staffers claimed in a 1996 memo that the church had “assumed an authoritarian role in our work in the Haitian community.”

Coalition instead of consensus

Another political conflict over Catholic Charities arose after same-sex marriage was legalized in Massachusetts in 2004. In 2005, a reporter revealed that the church had facilitated 13 adoptions of difficult-to-place children to gay couples in the state over the previous 18 years. After the practice became public, the church announced in 2006 that it would end its century-long adoption work so as not to violate church or state law.

Ultimately, says James, “there were structural dimensions that almost inevitably led to tensions at the institutional or organizational level.”

And yet, as James carefully reports, there was little consensus about the role of the church at the center. The center’s Haitian-American parishioners formed a coalition, not a bloc; some welcomed the church’s presence at the center for spiritual or practical reasons, or both.

“Many Haitians felt that independence (from the center) was beneficial, but others felt it would be difficult to maintain otherwise,” James says.

Some parishioners even expressed lingering respect for Boston’s Cardinal Law, a central figure in the Catholic Church’s sex abuse scandal that came to light in 2002; Law had personally championed the church’s charitable work for Haitians in Boston. In this light, James says, another question that emerges from the book is: “What makes people remain loyal to an imperfect institution?”

Keeper of the Flame

Among the people most loyal to the Haitian Multi-Service Center were its staff, whose work James describes in detail. Some staff members had themselves previously benefited from the center’s services. The facility’s loyal staff, James writes, served as “keepers of the flame,” understanding their history, building connections to the community, and expanding their own identities through good work for others.

Of institutions of this kind, James notes: “They seem to be most successful when there is transparency, solidarity and a strong sense of purpose. … This shows why we do the work we do and what we do to find meaning in it.”

Life at the Center has generated positive feedback from other scientists. Linda Barnes, a professor at Boston University School of Medicine, put it this way: “You could read ‘Life at the Center’ “I read it several times and discover new dimensions each time. Erica Caple James’ work is extraordinary.”

What is the state of the Haitian Multi-Service Center today? In 2006, it was relocated and is now housed with other facilities in the Yawkey Center of Catholic Charities. Some of the staff and parishioners, James writes in his book, feel that the center has died over the years compared to its independent self. Others simply see it as transformed. Many have strong feelings in one way or another about the place that helped them navigate as they built new lives.

James writes, “It was difficult to reconcile the intense emotions of many of the center’s stakeholders – confusion, anger, disbelief and frustration, which were still expressed violently decades later – with the memories of love, joy, laughter and care in service to Haitians and others in need.”

As Life at the Center makes clear, this intensity stems from the shared mission of many people to find their way in a new and unfamiliar land in the company of others. And as James writes at the end of the book, “Mission fulfillment is never just about the individual actions of individuals, but rather about the collective effort to help, educate, empower, and give hope to others.”