Scientists: Dolly Parton’s free book program not awake enough

Speech therapist hesitates to recommend reading aloud to children in general

A program that provides free books to children from birth to the age of five promotes “heteronormativity,” “ableism,” and “sexism,” according to a doctoral thesis.

Jennifer Stone looked at the 60 books in the Dolly Parton Imagination Library from a critical perspective of racial theory. The country singer’s foundation partners with libraries to distribute one book each month.

Stone has been a speech therapist for 25 years and has launched her own early reading initiative. She received her doctorate in speech and hearing sciences this spring. Based on the results of her study, she decided to stop recommending reading to children.

“The analyses revealed a diverse ethnic representation that interrupts the history of white dominance in children’s literature, accompanied by the maintenance of several hegemonic cultural stereotypes,” said Stone (pictured) wrote.

“Characters with disabilities, non-normative gender identities, or non-normative family structures were eliminated,” she wrote in her summary. “In addition, inconsistent messages were conveyed regarding books and reading.”

“No explicit references to sexual identity were found in the corpus,” she also complained.

It must be pointed out that this is a program for children.

“The characters’ relationships were subject to societal domination, exerted first by the mothers through childism, then by society through abilityism and sexism,” she wrote later in the article. “No models of cooperative mothers or same-sex partnerships challenged the pervasive heteronormativity or maternal enforcement in the characters’ familial relationships.”

“Three inductively derived themes – reading to succeed, living the American dream, and perfecting parenting – revealed complex intersections of power discourses that gave rise to an oppressive childism aimed at oppressing children and privileging a white, middle-class, cisgender, heteronormative, able-bodied American norm,” she wrote.

In her thesis, Stone explained how many of the books were problematic.

“(H)eterornormativity functioned as an implicit norm against which other family structures were compared,” wrote Stone. In other words, the children’s books too often promoted a mother and a father in the house.

Each book is coded with “family structure,” “race,” and “class,” an amazing feat considering that many characters are not human. In Goldilocks and the Three Bears, for example, the family is considered “white.” But they are not polar bears.

Books that promoted the work of people without disabilities were also criticized. “Individualized, capable bodies and actions were further portrayed as a desirable ideal through themes that celebrated the value of work,” the thesis states.

MORE: Researchers say ‘queering nuclear weapons’ can boost national security

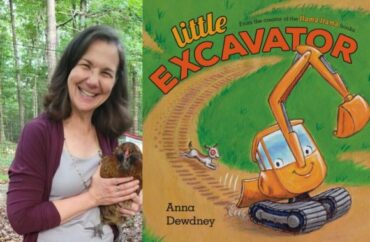

A book called “Little Excavator” has been criticized for extolling the benefits of work.

At the heart of the book “is the story of a young excavator operator who imitates the adult excavator operators so that he can one day join the large, adult excavator workforce,” Stone lamented. “It illustrates the widely accepted social convention that children are expected to identify a career path early in life and to work toward it with joy.”

She provided several other examples of workplace-centered books, all of which “located narrative action in work situations characterized by obedience to authority and daily participation in work as a form of meritocracy and a path to personal and financial success.”

Dolly Parton’s own book, Coat of Many Colors, was criticized by Stone for promoting the “American Dream,” the idea that people can succeed through hard work, and for including Spanish translations in the text.

In another book, Stone criticized it for promoting a “gender normative role” and for including a cross on the wall.

“Brick by Brick uses a first-person narrative, told from the point of view of Luis, a young bilingual boy, to describe how a Latinx family achieved the American dream,” Stone wrote. “It was written and illustrated by a white woman who used photographs, digital painting, and collage.” The family in the book hopes to one day buy their own home.

The book acknowledged how the family’s “work led them to realize this goal, and the sequence of images conveyed the movement through time and space for each phase of the dream’s realization.”

The mother wore, as Luis and Papi did, “a housecoat and slippers,” thereby implying a “gender-normative role by staying at home and cleaning while (her husband and son) went to work or school.”

“A cross hung on the wall, indicating a Christian family heritage,” Stone writes. “These images set the stage for a metaphorical rags-to-bones beginning for this family, whose native language was probably Spanish.”

However, Stone also praised the book for showing a non-white father supporting his child.

Stone said Parton’s free books program has done a good job of “incorporating characters of different races to a degree that could be groundbreaking in ongoing efforts to increase racial diversity in children’s literature.”

Stone, however, worries that the characters promote harmful narratives. “The (family literature theory)-based appreciation of racial representation in the corpus, however, coexists with the CRT-based analysis that identifies these inclusive images as potential sites for oppressive power,” she wrote.

Some books have used “melting pot” characters that represent a variety of ethnicities. This can be a good thing, Stone writes, but she believes it can also promote the dangerous idea of ”equal opportunity.”

“When included without cultural authenticity, melting pot representations can reinvigorate equal opportunity ideologies,” she wrote. “Equal opportunity ideologies obscure structural inequalities and place responsibility for successes and failures on individuals. In this corpus, melting pot representations have created a sense that everyone can participate in everything society has to offer, regardless of race.”

But according to Stone, these portrayals are “dangerous fictions” because “systematic racism denies people of color access to American educational, health and employment resources.”

The research prompted Stone to rethink the benefits of reading to children as a universal practice. She will continue to read to children, but will be careful not to promote “white saviorism” and other evils.

“I see the danger that the increasingly widespread prescription of daily reading aloud and book ownership as key elements of education could contribute to inequalities in literacy by telling mainstream stories and colonizing families’ basic knowledge with the cultural values of the dominant,” she writes. “The power of literacy and the inequalities it creates are so persistent that any risk justifies a pause and a careful reconsideration of accepted discourses.”

“For me, pausing and reflecting has led to a new understanding of literacy and literacy interventions,” she wrote.

“I now understand that literacy skills are diverse and dynamic and that literacy interventions are potentially dangerous and characterized by white saviorism.”

MORE: Vampires are a ‘queer icon’, scientists argue in new book

PHOTOS: University of North Carolina; Anna Dewdney/Viking Books for Young Leaders

Read more

How The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter