3 Questions: Catherine D’Ignazio on data science and the search for justice | MIT News

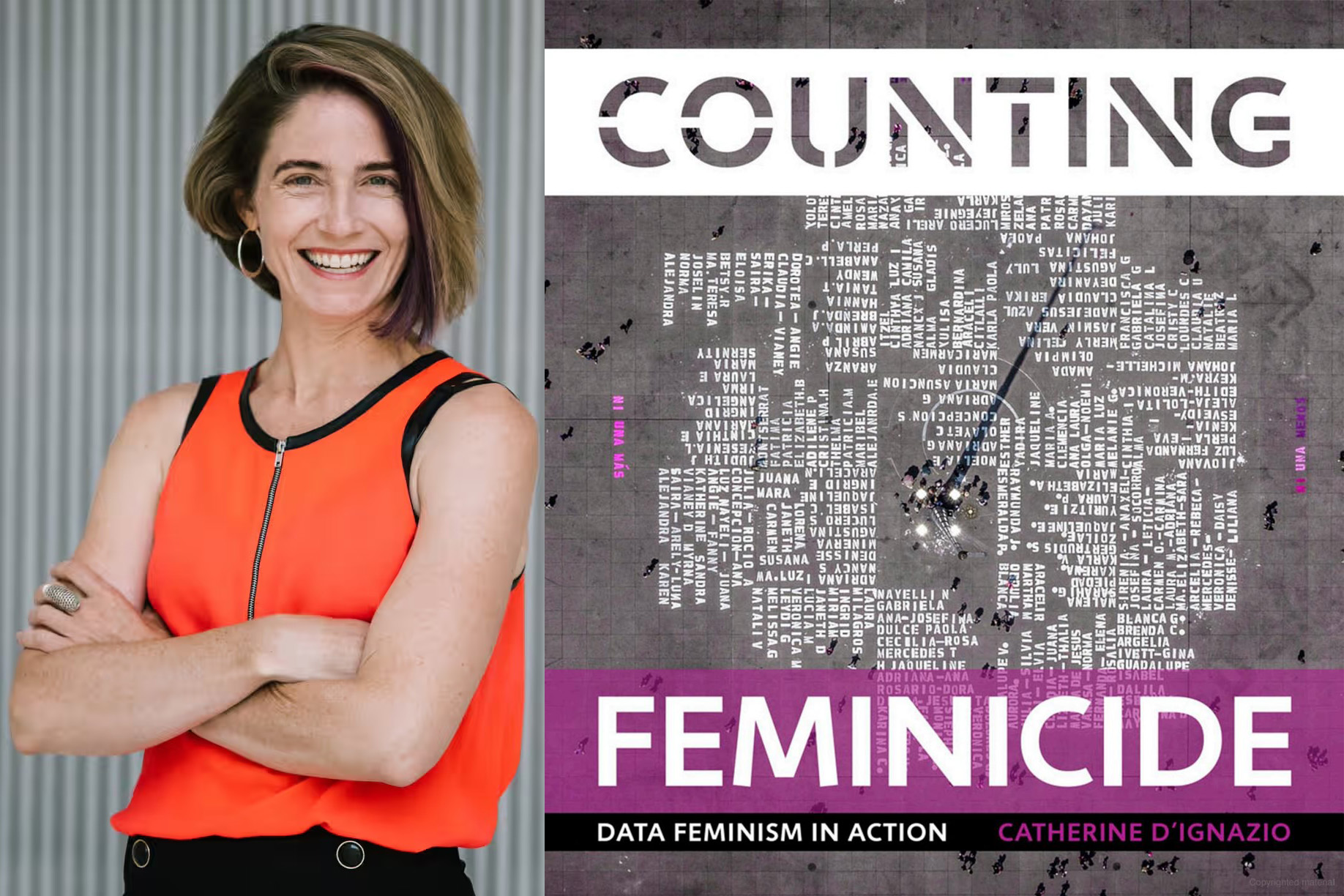

As long as we apply data science to society, we should remember that our data may contain errors, biases, and gaps. This is a theme of MIT Associate Professor Catherine D’Ignazio’s new book, Counting Feminicide, out this spring from MIT Press. In it, D’Ignazio explores the world of Latin American activists who began using media reports and other sources to determine how many women were killed by gender-based violence in their countries—only to find that their own numbers diverged sharply from official statistics.

Some of these activists have become prominent public figures, others less so, but all have produced works that teach lessons about collecting and sharing data and applying them to projects that advance human freedom and dignity. Their stories are now reaching new audiences thanks to D’Ignazio, an associate professor of urban science and planning in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning and director of MIT’s Data and Feminism Lab. She is also hosting an ongoing transnational conference exploring how to collect and share data. Book Club about the work. MITNews spoke with D’Ignazio about the new book and how activists are expanding the traditional practice of data science.

Q: What is your book about?

A: Three things. It’s a book that documents the rise of data activism as a really interesting form of citizen data science. Because of the availability of data and tools, collecting and conducting your own data analysis is increasingly becoming a growing form of social activism. We characterize this in the book as citizen practice. People are using data to make knowledge claims and to make policy demands that their institutions must respond to.

Another finding is that data activists have very different approaches to data science than what is usually taught. Among other things, work on inequality and violence has a connection to the data sets. It’s about memorializing the people who lost their lives. Mainstream data scientists can learn a lot from this.

The third point is about feminicide itself and the lack of information. The main reason people start collecting data on feminicide is because their institutions don’t. This is true of our institutions here in the United States as well. We’re talking about violence against women that the state doesn’t count, classify, or act against. Activists fill in those gaps and do so to the best of their ability, and they’re quite successful at it. The media turns to the activists, who eventually become authorities on feminicide.

Q: Can you elaborate on the differences between the practices of these data activists and traditional data science?

A: One difference is what I’ll call the familiarity and proximity to the rows of the dataset. In traditional data science, when you’re analyzing the data, you’re not usually the data collector. But these activists and groups are involved across the entire pipeline. As a result, there’s a connection and a humanization to every row of the dataset. For example, there’s a school nurse in Texas who runs the website Women Count USA, and she spends many hours finding photos of victims of femicide, which is an unusual level of care given to every row of a dataset.

Another point is the sophistication of data activists in terms of what their data represents and what biases are in the data. There are still conversations in mainstream AI and data science where people seem to be surprised that data sets are biased. But I was impressed by the critical sophistication with which activists have approached their data. They gather information from the media and are familiar with the biases of the media and are aware that while their data is not comprehensive, it is still useful. We can put those two things together. It is often more comprehensive data than what the institutions themselves have or will release to the public.

Q: You not only documented the work of activists, but also worked with them and reported on it in the book. What did you work on with them?

A: A key part of the book is the participatory technology development we did with the activists. One chapter is a case study of our work with activists to co-develop machine learning and AI technology that supports their work. Our team thought about a system for the activists that would automatically find cases, verify them, and enter them directly into the database. Interestingly, the activists rejected that. They didn’t want full automation. They felt that actually being a witness is an important part of the job. The emotional load is an important part of the job and very central as well. That’s not something I would always expect to hear from data scientists.

Keeping the human in the loop also means that the human makes the final decision about whether or not a given item constitutes femicide. Dealing with it this way is consistent with the fact that there are multiple definitions of femicide, which is a complicated matter from a computational perspective. The multitude of definitions of what counts as femicide reflects the fact that it is an ongoing global, transnational discussion. Femicide has been codified in many laws, particularly in Latin American countries, but none of these single laws is final. And no single activist definition is final. People create this together, through dialogue and struggle, so any computational system must be designed with this understanding of the democratic process in mind.