‘Nobody needs your English single’: Russian anti-war artists struggle to stay relevant in exile

“Stop drinking and think about your income, my star. Overseas, you’ll rot in a stinking backyard. Nobody needs your English single in the English-speaking world.”

This is the lyrics of “Kalinkathe first English-language track from popular exiled rapper Noize MC. The song captures the struggle of the many Russian artists, musicians and comedians who have left the country and are trying to resonate with European audiences.

As newcomers, they face tough competition from Western artists who have long been established on the scene. And there is no right answer to the question: should they switch to English or continue to perform in Russian?

Many, like Noize MC, have switched to English, although the rapper expresses concern in the lyrics of “Kalinka” that he might never be popular in the “Anglophone world.”

“Kalinka” is set to the music of the Russian folk song of the same name and is intended to evoke nostalgia for the homeland, an ironic contrast to the artist’s real experiences in Russia.

In December 2021 Government launched an investigation into Noize MC’s lyrics for “extremism” after writing a sarcastic social media post. The rapper left Russia and received a humanitarian visa to Lithuania with his family in early 2022.

Speaking to the Moscow Times on the messaging app Telegram, Noize MC, whose real name is Ivan Alexeyev, said he wanted to reach more international listeners as well as his core audience, emigrated Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians.

The challenge is to “stay connected to my roots” while writing more songs in English to “spread my message worldwide,” he said.

This message is a political one.

“Music is a powerful tool to raise awareness and inspire change, and I believe it is crucial to use my platform to speak out against oppression and support those fighting for their rights,” said Noize MC.

He also wants to get those whose lives “have been turned upside down and will never be the same” to focus on thinking about who we are, what cultural significance we have for our country while we are away from home, and what cultural legacy we can leave behind.

For stand-up comedians, the linguistic challenge is greatest: Denis Chuzhoia comedian living in Berlin, talks about his difficulties in being funny in English compared to his native Russian, and about his everyday worries related to migration.

“What if I cheated at university and my English isn’t real? Will people laugh at me just because I sound like the madman in town?” he wrote after one of his appearances on X (formerly Twitter).

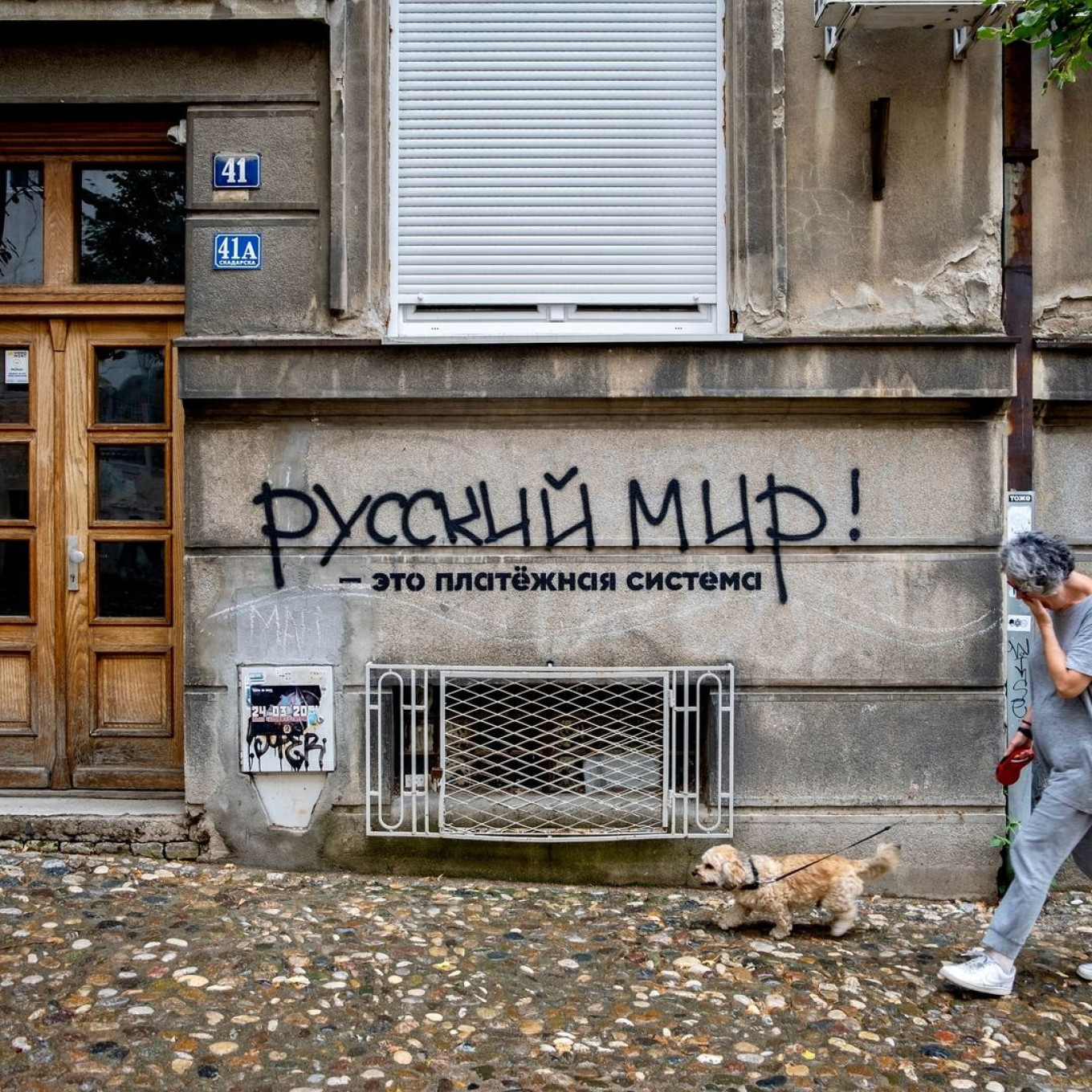

Other artists continue to work in their native language, such as street artists Andrey Tojewho creates works in Russian in his new homeland of Serbia. Most recently, he covered pro-war Z symbols often found on Belgrade’s streets with glass and the instruction “In case of emergency, break glass.”

Andrey Toje @andreytoje

Toje said his creativity disappeared for a year after he moved to Serbia in 2022.

“I had used up all my ideas in Russia and was just concentrating on survival. I slept on friends’ sofas with just a towel,” he said.

Over time, he found the motivation to continue making art that was aimed at the Russian audience and, above all, had to do with the war.

“The issue is still relevant and we should not forget it. I can’t do anything funny while this is still going on,” said Toje.

“My motivation is to create a dialogue between Russian speakers here. Maybe they will take photos and share them. The topic is negative, but people often smile when they see it. Instead of generating hatred, it evokes positive emotions,” he continued.

The challenge is whether the diaspora, which is now largely tired of the issue of war and focused on its life as migrants, will pay attention to the issue.

In contrast, Ploho, a Siberian post-punk band known for their deep voices and masterful guitar playing, left Russia in 2022 and is now touring Europe to attract new audiences.

Leaving home changed the band’s music.

Ploho frontman Viktor Uzhakov said: “Life in Novosibirsk was a depression in itself and that was reflected in our songs. Now our music is less depressing… (it’s) more about love and social issues.”

However, they plan to continue performing and writing in Russian.

Uzhakov, who directed the Void music festival in the city of Novosibirsk until it was raided by police in 2016, said: “To write songs in another language, you need to be able to think and live in it. Unfortunately, that’s not the case with me.”

He once experimented with a German recording of his song and said he might do it again, but it wasn’t easy.

Despite the language barrier, Uzhakov meets not only the Russian diaspora but also many locals during his performances in Europe.

At the same time, it remains difficult for the band to measure their success.

“The halls that are made available to us are usually full and they don’t throw rotten tomatoes at us… that’s something,” he said.

Throughout 2022, Ploho’s European performances, like those of many other Russian artists, were cancelled as venues chose to support Ukraine, despite the band’s anti-war stance.

Touring is slowly returning to normal. “Little by little, European countries have realized that we are not terrorists or madmen and we have not occupied anyone’s land. We are just a band that makes music and we want to continue doing that,” said Uzhakov.

Although visa restrictions are becoming an increasing obstacle, Uzhakov said: “When you live in Russia, you get used to the difficulties.”

Artist programs in France and Germany have been the most supportive of Russian exiles. Ploho will receive an artist visa in France that will grant him a residency permit. Toje, meanwhile, hopes to stay long-term in Belgrade, where an estimated 300,000 Russians live.

Neither Uzhakov of Ploho nor Toje had planned to go abroad before the war.

Uzhakov said that while he liked the people and structure of European society, he admitted he could never become a part of it.

“I’m not the type of person who is willing to integrate into another country, language and culture,” he said. “I never planned this and now it’s a necessary measure – not the romance of moving to Europe.”

… we have a small request. As you may have heard, The Moscow Times, an independent news source for over 30 years, has been wrongly branded a “foreign agent” by the Russian government. This blatant attempt to silence our voice is a direct attack on the integrity of journalism and the values we hold dear.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, will not be silenced. Our commitment to accurate and unbiased reporting on Russia remains unwavering. But we need your help to continue our critical mission.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a big difference. If you can, please support us monthly from just $2. It’s quick to set up, and you can rest assured that you’ll have a meaningful impact every month by supporting open, independent journalism. Thank you.

Keep going

Not ready to support today?

Remind me later.

×

Remind me next month

Thank you! Your reminder is set.

We will send you a reminder email once a month. For details about the personal data we collect and how we use it, please see our Privacy Policy.