Why a 12-year-old took action against period poverty

A 12-year-old girl in Germany was so touched by the inspiring work of South African anti-period poverty activist Tamara Magwashu that she managed to organize a large donation to charity.

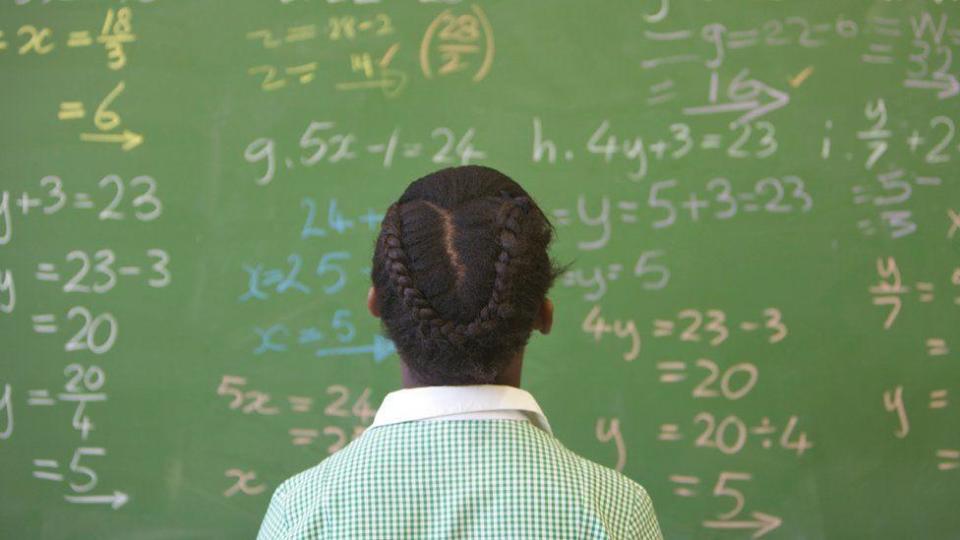

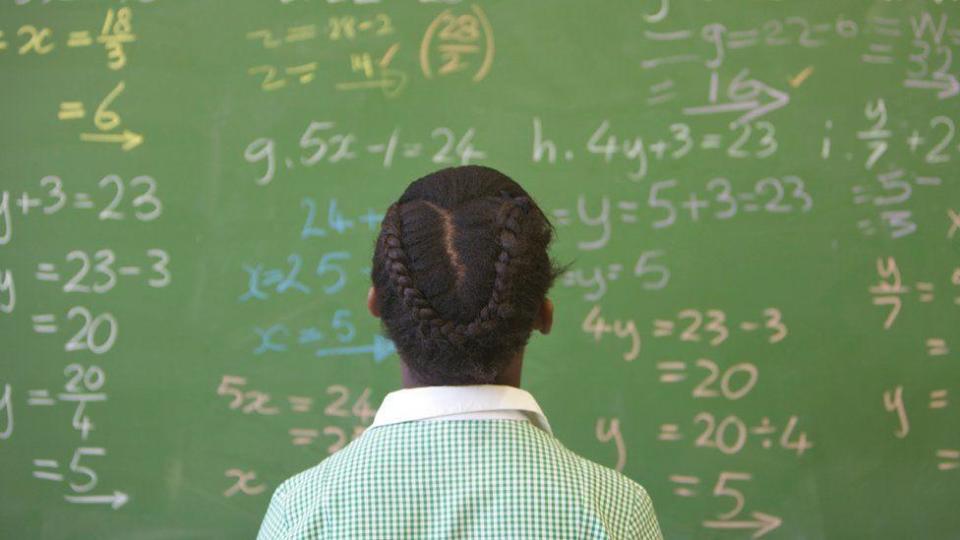

Caity Cutter was shocked to learn from a BBC article about Ms Magwashu that 30% of girls in South Africa do not go to school during their period.

Ms Magwashu described Caity’s efforts as life-changing.

The story, published a year ago, was about how the now 28-year-old from South Africa’s Eastern Cape province helped girls who could not afford sanitary pads by distributing them free of charge to schools in rural, impoverished areas.

Having grown up in a slum where she used rags as sanitary pads – and was bullied for it – Ms Magwashu was determined to prevent other girls in her community from suffering the same fate.

She started her own business to help girls in the country and elsewhere.

“Deep down I made the decision that I don’t want anyone to go through what I went through,” Ms Magwashu told the BBC.

“My goal is to reach every girl in need so that they can maintain their dignity. Depriving a woman of sanitary products is a violation of her human rights.”

For Caity, this determination was inspiring – but also a revelation.

“I found it really sad that girls my age didn’t have access to clean water, period products and toilets,” she said.

Ms Magwashu had explained that her family shared a public toilet with about 50 other people in Duncan Village, a town near East London.

“I think it’s crazy that we live in a world where some people can go to the moon and others don’t have a toilet,” Caity said.

Her father, Michael Cutter, had been saving money from his job at a biopharmaceutical company for some time and wanted to donate it to charity.

His daughter convinced him that it would be worthwhile to support Mrs. Magwashu’s project.

It was an overwhelming moment for the South African.

“They donated 500,000 sanitary pads to help marginalised girls. Further donations then went to us to build a warehouse and employ staff to distribute the pads further,” she told the BBC.

The entire amount went to Ms Magwashu’s non-profit organization Azosule, whose charitable arm distributes free sanitary pads to schools in the poorest communities and sells cheaper, sustainable hygiene products.

Ms Magwashu has negotiated a deal with South African supermarket Makro to make her sanitary pads available in their stores across the country and in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

An estimated seven million girls in South Africa cannot afford sanitary products.

South Africa is just one of many countries that suffer from period poverty.

According to the World Bank, at least 500 million women and girls worldwide suffer from period poverty, which leaves them with little access to the services they need during their period.

In August last year, the BBC conducted a pan-African investigation to examine the impact across the continent and found that women in Ghana who earn minimum wage spend one in seven dollars they earn on sanitary pads.

However, it is not just the cost and availability of the pads themselves that matters.

The poverty research organization J-Pal Africa examined the impact on girls’ education in Madagascar and addressed the lack of knowledge about hygiene practices.

2,250 students from 140 primary and secondary schools took part in the study.

One conclusion of the study was that students’ general academic skills, memory and attention improved after adequate washing facilities were built, teachers were trained, and vouchers for free sanitary pads were distributed.

In addition, girls were 17% more likely to be promoted to the next grade.

Through her interactions with Ms Magwashu, Caity says she also understood that funding period products was “only part of the solution.”

Ms Magwashu also sends teams to schools to educate girls and boys about menstrual hygiene.

Azosule is a labor of love for Ms Magwashu, a PR graduate, who saved money from part-time jobs and her student loan to start the company in 2021.

Originally, she did this through so-called “pad drives,” where you load up a vehicle and drive to poor areas to distribute hygiene products.

But now she can achieve more with a larger team.

“With this (the donation) we are able to help more schools and are talking to schools in Congo-Brazzaville, where many girls have never seen a sanitary pad,” Ms Magwashu told the BBC.

She hopes that one day this will be the case across the continent.

Referring to the donation from Germany, Ms Magwashu added: “I felt seen and heard for once, because we are talking about a person who comes from a privileged background and does not have to experience period poverty.”

“When I say it completely changed my life, it really did.

“Caity will always be one of my heroes. She not only changed my life, but also the lives of thousands of other girls so that they don’t have to go through what I went through.”

You might also be interested in:

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/IS7QZ2BYIJDGPJ2WGEP5CPHLUY)

)