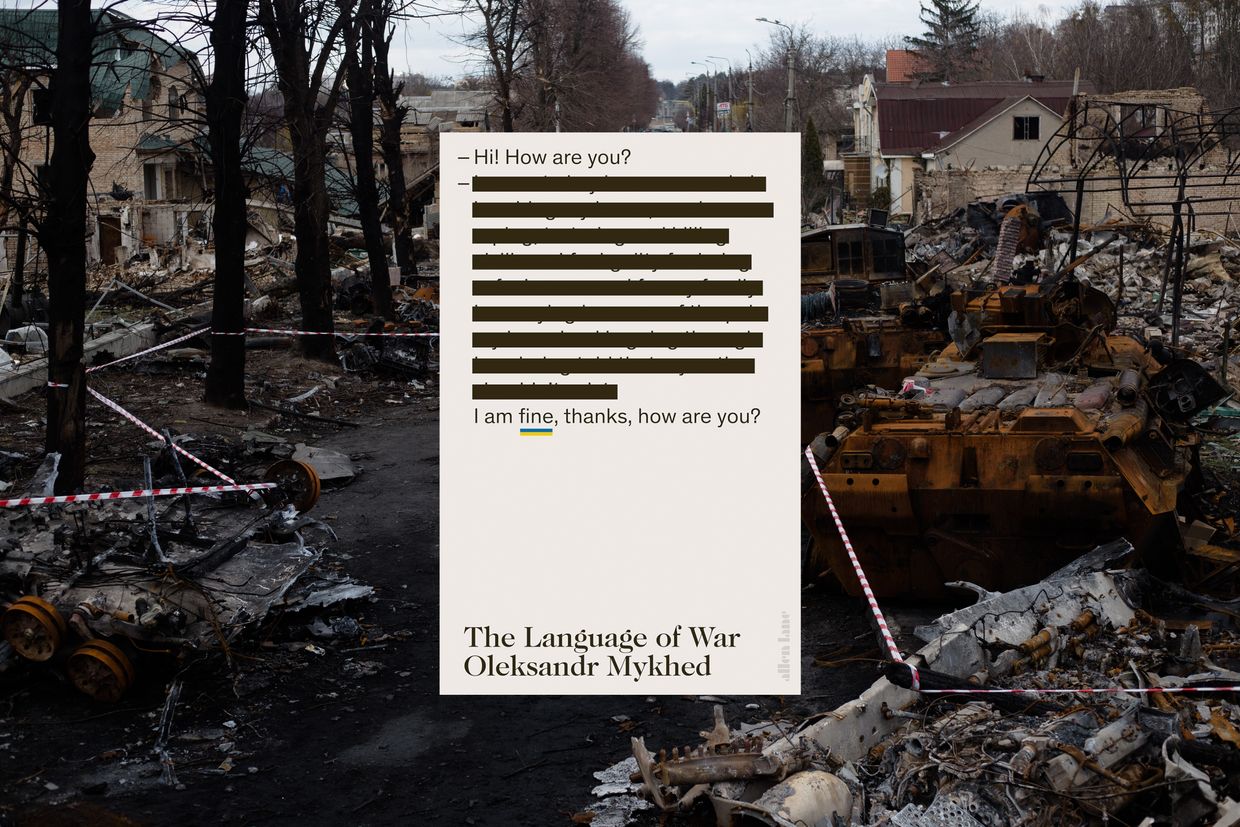

“The language of war” is that of anger, but also of love

“How should I deal with this anger? Or should I?” asks Ukrainian author Oleksandr Mykhed after the start of open war in Russia.

In his book The Language of War, the first major Ukrainian prose work published by Penguin, Mykhed tells how Ukrainians’ lives were turned upside down on the night of February 24, 2022. The need to find the right words to express this anger and all the other emotions the war provoked remains pressing throughout the book. Mykhed describes how “the war now lives in us,” underlining that this is not just a struggle for survival in a genocidal war, but a profound shift in the way Ukrainians relate to each other and the rest of the world.

Mykhed and his wife fled their home in Hostomel, a suburb of Kyiv that was the scene of heavy fighting in 2022, towards western Ukraine. But they initially failed to convince his parents, who lived in nearby Bucha, to do so.

As a result, Mykhed’s parents lived under occupation in Bucha for nearly three weeks. The city’s name became synonymous with Russian war crimes as terror reigned there, including the murder of over 450 people. For obvious reasons, the passages in the book where Mykhed describes his parents’ ordeal in Bucha are some of the hardest to read – one can only imagine the emotional toll it took on him to write them and process what his parents had to endure.

Mykhed also transcribes his mother’s statements from this period and his reflections on their family’s history, which goes back to World War II. The need to talk about these layers of trauma offers the opportunity to finally free oneself from them, as they can otherwise completely consume one.

After she and Mykhed’s father fled Bucha and were reunited with her son in Chernivtsi, a city in western Ukraine, things that had once given her joy, such as reading, no longer appealed to her in the days that followed.

“I have to surround myself with calm,” she tells her son. “I guess that’s my reaction to the sounds of the explosion and everything that happened there.”

The book includes not only the war experiences of Mykhed and his family, but also testimonies from other Ukrainians who experienced the war in Russia, including a “cyborg,” a nickname for the Ukrainian soldiers who bravely fought to defend Donetsk International Airport during heavy fighting in 2014.

In addition, there are chapters listing the numerous war crimes committed by Russian soldiers on Ukrainian soil. These include the burning of the Ivankiv Local History Museum, which housed 25 works by Ukrainian folk artist Maria Prymachenko, and the use of phosphorus bombs by Russian troops in the suburbs of Kyiv. The use of such weapons is prohibited by the Geneva Convention.

As the title of the book suggests, war changes the way people communicate. The language of war is not a language of culture, business or leisure. This is underlined by how Mykhed’s parents struggle to communicate with friends who have fled abroad. While they complain about things like the state of their accommodation, his parents struggle to find the right words to describe what the occupation was like, and ultimately conclude that it is better to say nothing at all. War not only destroys people’s homes and lives, but also some of the previous ways in which they had contact with each other.

Mykhed also struggles to find meaning in his work as a writer and cultural worker. In Chernivtsi, he helps to clear books from a library’s storage room to set up an air raid shelter. He enlists in the Ukrainian armed forces and “deeply regrets” that he learned how to assemble and disassemble a weapon only a week before the start of the full-scale war.

“We will emerge from this war as a changed people,” writes Mykhed. “Apart from creative writing, all my previous experiences seem exaggerated and unnecessary.”

“The names of film directors and authors, literary methods and artistic creations seem to me too convoluted and unnecessary in the language of war. My mind avoids access to all layers of complex knowledge and focuses instead on the deeply philosophical concept of ‘shithead invaders.'”

As Russia’s all-out war disrupts Ukrainians’ way of life and forces them to prioritize survival, Mykhed also struggles with guilt. He himself does not suffer from survivor guilt, he explains. This guilt has more to do with his “not being able to understand the horror” experienced by people fleeing the Russian invasion of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in 2014, until he himself lost his home.

He feels guilty for having “done so little” in the eight years leading up to February 24, 2022, when so many soldiers and volunteers sacrificed their lives to contain the initial Russian invasion of eastern Ukraine. In addition, he feels guilty for failing to convince his parents to evacuate Bucha before they were trapped under occupation, and ponders finding the right words to write a self-help book on the subject.

“Because one of the lessons I have learned in these weeks is that the whole world must be ready to leave everything behind,” writes Mykhed.

Mykhed also appeals to those in the West who support Ukraine but define its existence in relation to Russia: “We are something completely different. A young, independent, dynamic nation that knows its history and has its own vision of the future.”

For many people around the world, Russia’s open war brought attention to the country and put Ukraine on the map for the first time. But the lack of appreciation for Ukraine’s rich language, history and culture, which have survived despite generations of Russification policies and state-sponsored violence against the population, means that these people often do not fully understand what Ukrainians are fighting so fiercely for.

“I want to shout out to the world: We are bigger, more interesting, broader than the box we have been put in,” writes Mykhed. “We are bigger than the war.”

A disturbing result of this narrow perception is that it has mostly been well-meaning organizations abroad that have attempted to promote dialogue between Ukrainians and so-called “good” Russians who have fled Russia. Over the past two and a half years, there have been numerous incidents in which Ukrainian artists have publicly withdrawn their participation in major cultural events that also featured Russian artists. Although Ukrainian artists have repeatedly explained why they believe that any semblance of dialogue during the war would be detrimental to the Ukrainian cause, such controversies continue to arise.

Many Western media have also given a platform to Russian artists who not only lament the circumstances of their lives in exile, but use the opportunity to complain about what they see as the hostile attitude of Ukrainians towards them. They complain, for example, about the dismantling of monuments to the 19th century Russian poet Alexander Pushkin throughout Ukraine, which are insignificant in the overall context.

“We share your pain,” Mykhed answers them. “All of us here in a bomb shelter.”

Russia’s all-out war is not the first act of aggression against Ukraine, even in Mykhed’s lifetime. If Russia is not defeated “in the clutches of its hungry empire,” as Mykhed suggests, then these cycles of tragedy point to a harsh realization that he calls a Ukrainian life lesson: He and his loved ones will likely have to live through this again.

“The experiences I am gaining now will be of crucial importance to me later,” he writes, even at a time when he will reach an age that he “cannot even imagine.”

Mykhed’s The Language of War offers a sobering look at the first year of the large-scale invasion, and not just through the eyes of his family and other Ukrainians. The book forces readers to confront the brutal reality of war, beyond the more palatable narratives of resilience and fortitude often presented by outside observers.

The book presents numerous examples of Ukrainians who have overcome the inhumanity of the Russian forces and drawn strength from the shared experience. However, Mykhed stresses that the scale of the horror that took place must never be forgotten.

Mykhed’s outrage is great and justified. Such atrocities were considered unthinkable in the 21st century until countries like Russia proved the opposite to the world.

“This book is about things you can never forget,” he writes. “Or forgive.”

Author’s note:

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan. Thank you for reading this article. There are more and more books about Ukraine for English-speaking readers and I hope my recommendations will be helpful on your next visit to the bookstore. Ukrainian culture took on even more importance during the war, so if you like reading about such things, PConsider renting support The Kyiv Independent.

Ten books to better understand Ukraine during the war

Ukrainian writers should have devoted their lives to honing their craft. Instead, many of them have devoted themselves to the war effort and the fight against Russian aggression. Like any other member of society, Ukrainian writers have lost loved ones and colleagues to Russia.