Root cause of lupus found in tug-of-war over critical white blood cells: ScienceAlert

The autoimmune disease lupus – officially called systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) – is difficult to treat and a burden on life.

The random bouts of pain, inflammation and fatigue that accompany the disease are a “cruel secret” of no known cause that affects 1.5 million people in the United States by irreparably damaging virtually every organ, including the kidneys, brain, and heart.

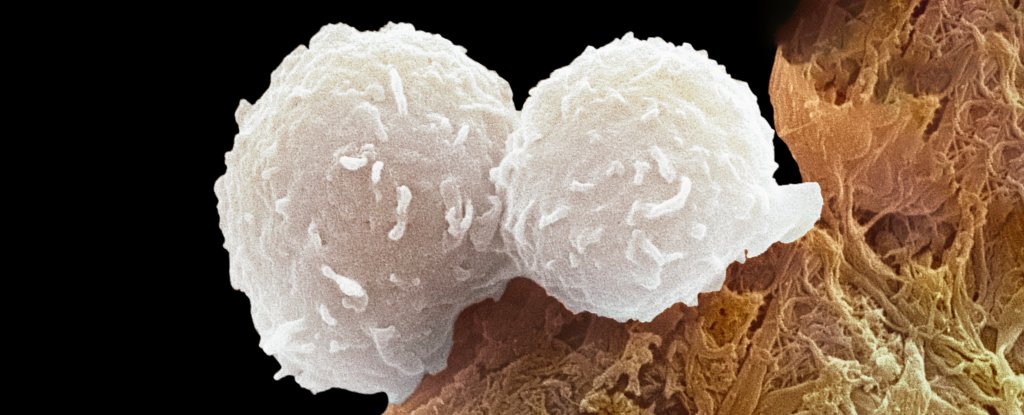

It is believed that immune cells, so-called T helper cells, are overactive in patients with SLE. Scientists may have finally identified a key root cause of the problem. A thorough study led by researchers at Northwestern University and Brigham and Women’s Hospital has delved into the details and revealed an imbalance that could worsen other symptoms.

“So far, every therapy against lupus has been a blunt instrument. It is a broad immunosuppression,” explained Immunologist Jaehyuk Choi from Northwestern University.

“By identifying the cause of this disease, we have found a potential cure that does not have the side effects of current therapies.”

A team of dozens of scientists led by biochemist Calvin Law of Northwestern University and immunologists Vanessa Sue Wacleche and Ye Cao of Brigham and Women’s Hospital conducted the current study. The results suggest that the immune systems of lupus patients are fundamentally immune.balanced.

Blood tests of 19 patients with SLE and 19 participants without autoimmune disease showed significant differences in the expression of different types of T helper cells.

These important immune cells are responsible for stimulating the production of other immune cells, which in turn produce antibodies – proteins that normally bind to foreign substances and pathogens to mark and neutralize them.

To understand the importance of differential T cell expression, imagine a tug of war where the knot in the middle is a T cell that can potentially take two different shapes. If the knot is pulled in one direction, the T cell will be expressed in a certain way and become a type of T helper cell. If the knot is pulled in the other direction, the T cell will be expressed in an opposite way.

Those without an autoimmune disease have strong powers in activating the Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), the pulls the T cell decisively to one side.

This receptor is taken into account “critical for the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity” and is associated with many autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease and SLE.

In patients with SLE, the AHR on T cells is insufficiently activated. A counterforce, driven by a A signaling molecule called interferon type I appears to distract the T cell from its typical expression and function.

The result is too many immune cells, which promote autoantibodies that attack the body’s own cells and trigger more type I interferon, creating a positive feedback loop.

When the researchers again added AHR-activating molecules to the blood samples of the lupus patients, the immune cells returned to balance.

“We found that by either activating the AHR pathway with small molecule activators or limiting pathologically excess interferon in the blood, we can reduce the number of these disease-causing cells,” says Choi.

“If these effects are permanent, this could be a potential cure.”

There is still a long way to go before a drug based on these findings can be proven safe and effective for treating SLE. However, given the few treatment options available to patients today, the new findings are a hopeful start.

“We believe the opportunity here is not to generally suppress the immune system of patients with autoimmune diseases,” explains Choi, “but to reprogram the cells that actually cause the disease.”

The study was published in Nature.