The reprint that probably saved Catwoman’s existence

Summary

- In the 1950s, the Comics Code Authority threatened to erase Catwoman from history, causing her to disappear for over a decade.

- DC brought back classic characters like Catwoman in reprints in the 1960s, ensuring their existence in pop culture.

- Catwoman’s appearance in 1964’s 80-Page Giant likely influenced her inclusion in the Batman television series, ensuring her continued popularity.

Knowledge Waits is a column where I simply share a bit of comic book history that interests me. Today I’m looking at the comic book reprint that could have very well saved Catwoman’s existence as a pop culture character.

I would do this as “Comic Book Legends Revealed,” but I think it’s probably a BIT too much conjecture for me to really say one way or the other, so I’m just going to lay it out here as something I think is VERY LIKELY to be the case.

As you may or may not know, Catwoman, like many of Batman’s other villains, got caught in a weird moral panic in the 1950s when the Comics Code Authority came into effect. While the Comics Code didn’t specifically BANNED a sexy thief that Batman isn’t sure if he wants to kiss or catch, it didn’t elevate the character either. See, even BEFORE the Comics Code Authority came into effect, DC was stricter with its own content, so it had NO problems with the Comics Code, because Senate hearings about comics corrupting little children sure wasn’t good business for National Comics (DC’s name at the time).

As I mentioned earlier, the great Tim Hanley wrote a book a few years ago called The Many Lives of Catwoman: The Criminal Story of a Deadly Cat (You can find more information about the book on his website here. Buy a copy.) He discussed that era:

The Senate hearings began immediately after the publication of Seduction of the Innocent in late April 1954, and Catwoman’s jungle adventure with Batman and Robin in Detective Comics #211 hit the newspapers three months later. This was about the lead time for comics during this period; the issue was probably shelved even before Seduction of the Innocent was published. Catwoman appeared regularly in Batman and Detective Comics in the early 1950s, usually every few months, but she disappeared for more than a decade after Seduction of the Innocent came out. The timing suggests that this was because she was one of the few other characters mentioned by name in Wertham’s Batman section.

And in an unkind way. In the midst of Wertham’s discussion of homoeroticism, he noted, “There are virtually no decent, attractive, successful women in these stories.” As an example, he suggested, “A typical female character is Catwoman, who is vicious and uses a whip.” These are unkind descriptions of Catwoman, but not enough to condemn her to irrelevance. More damaging was Wertham’s connection of Catwoman’s role to the gay undertones of the comics, when he continued, “The atmosphere is homosexual and anti-feminine. If the girl is good-looking, she is undoubtedly the villain. If she is after Bruce Wayne, she has no chance against Dick.”

So Tim’s theory was that DC moved away from Catwoman and quickly made recurring character Vicki Vale a permanent fixture on the series as a love interest for Bruce Wayne, and subsequently introduced Batwoman as a love interest for Batman.

Batman editor Jack Schiff then largely turned away from supervillains, PERIOD, although the big ones like Joker and Penguin continued to appear. So Catwoman was really in danger of just disappearing into history. But luckily for them, DC found a way to make money at very little cost in the 1960s, and that might have saved Catwoman’s existence in pop culture!

Related

How Peanuts handled the 4th of July over the years

See how Charles Schulz had the Peanuts gang celebrate the 4th of July over the decades

How did DC bring back its classic characters from the early 1960s?

The idea of publishing “Annual” comics that cost more was based on an old English tradition among children’s magazines, which typically published an oversized “Annual” at Christmas (when parents wanted to buy presents for their children). Archie Comics followed this approach in the 1950s, and DC followed suit in 1960 with a Superman Yearbook and a Batman Yearbook in 1961. These were oversized reprint comics that cost 25 cents (twice as much as a regular issue of Superman or Batman costs at the time).

These sold so well that DC began to publish 80-page giant magazines more regularly (it was a book called 80-page giant(except that each issue focused on a different hero until DC simply shifted the concept to single issues of each series), full of reprints of stories for which DC was not paying any royalties, so it was almost all about profit, and since there was no real market to speak of for older issues, this was the first time that modern readers of the 1960s could READ some of these classic older stories.

Jack Schiff, in turn, realized that he could use these reboots to bring some of Batman’s now-discarded classic villains into the spotlight, which turned out to be quite a stroke of luck for a number of characters.

Related

Legion of Super-Heroes: Brainiac 5’s complicated romantic past

It was recently revealed that Brainiac 5 of the Legion is demisexual. We explore what that means and how his comic book history supports such a notion.

What influence did DC’s 80-page behemoths have on the Batman television series?

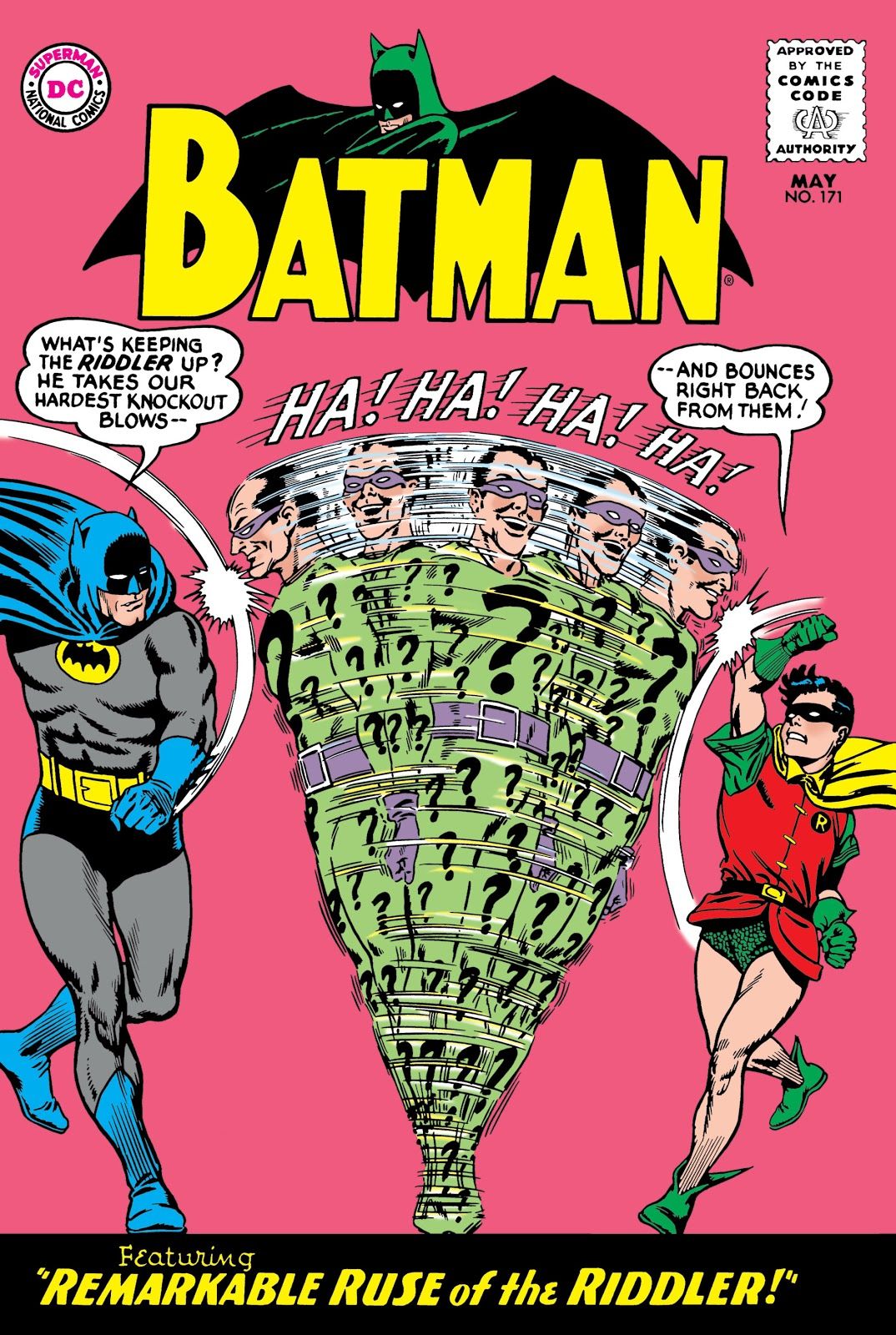

As I noted in a recent Comic Book Legends Revealed, in 1965 producer William Dozier went out and bought some newer and older Batman comics (I told the whole story in an old Comic Book Legends Revealed here) and one of the new comics he bought was Batman #171, which marked the return of the Riddler to the Batman universe…

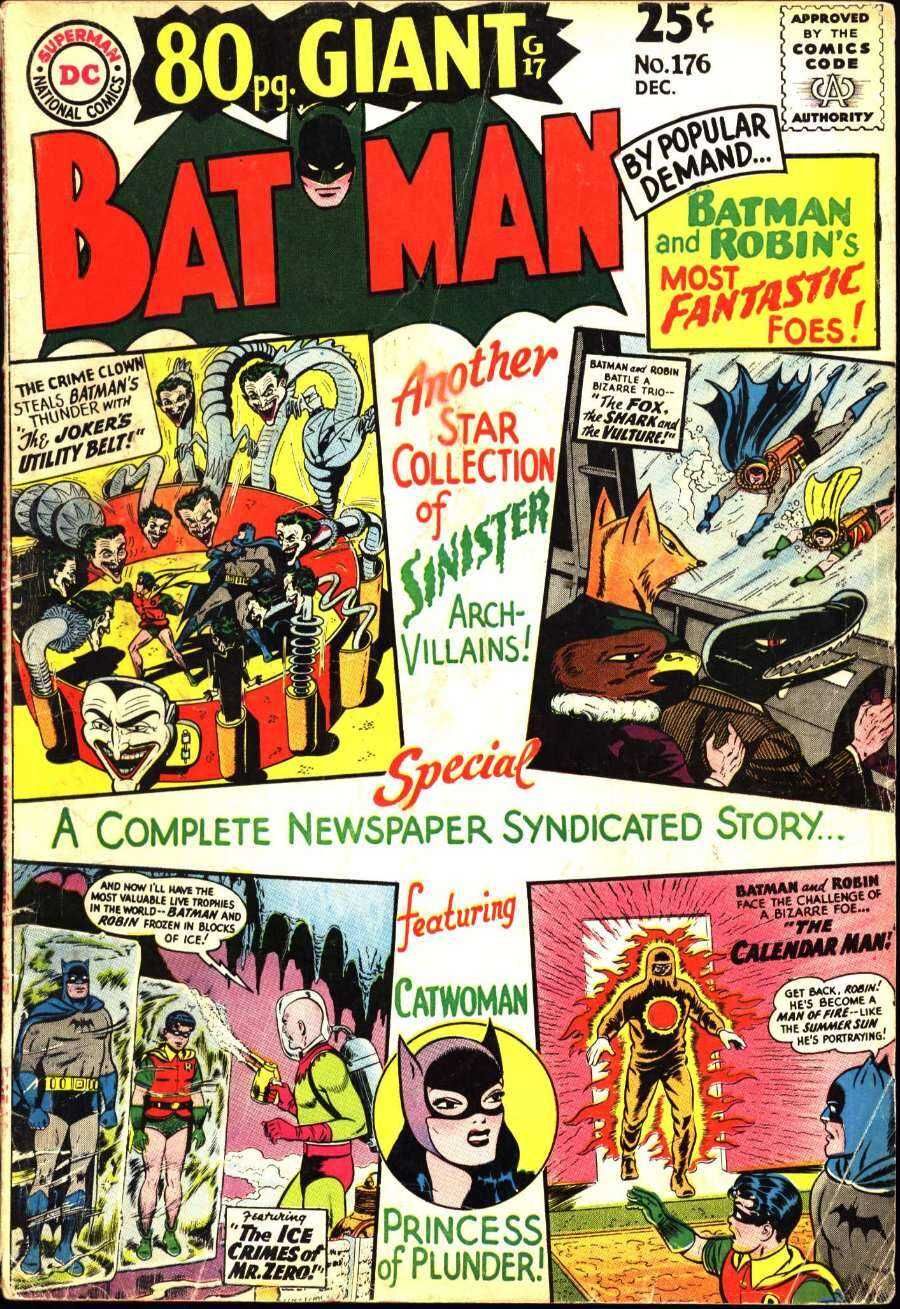

Another important topic, however, was Batman #176 in October 1965, which featured THREE of the first four episodes (or six of the first eight, since they were two-parters) of the Batman television series the following year, which, among other things, led to the revival of the character that would become Mister Freeze!

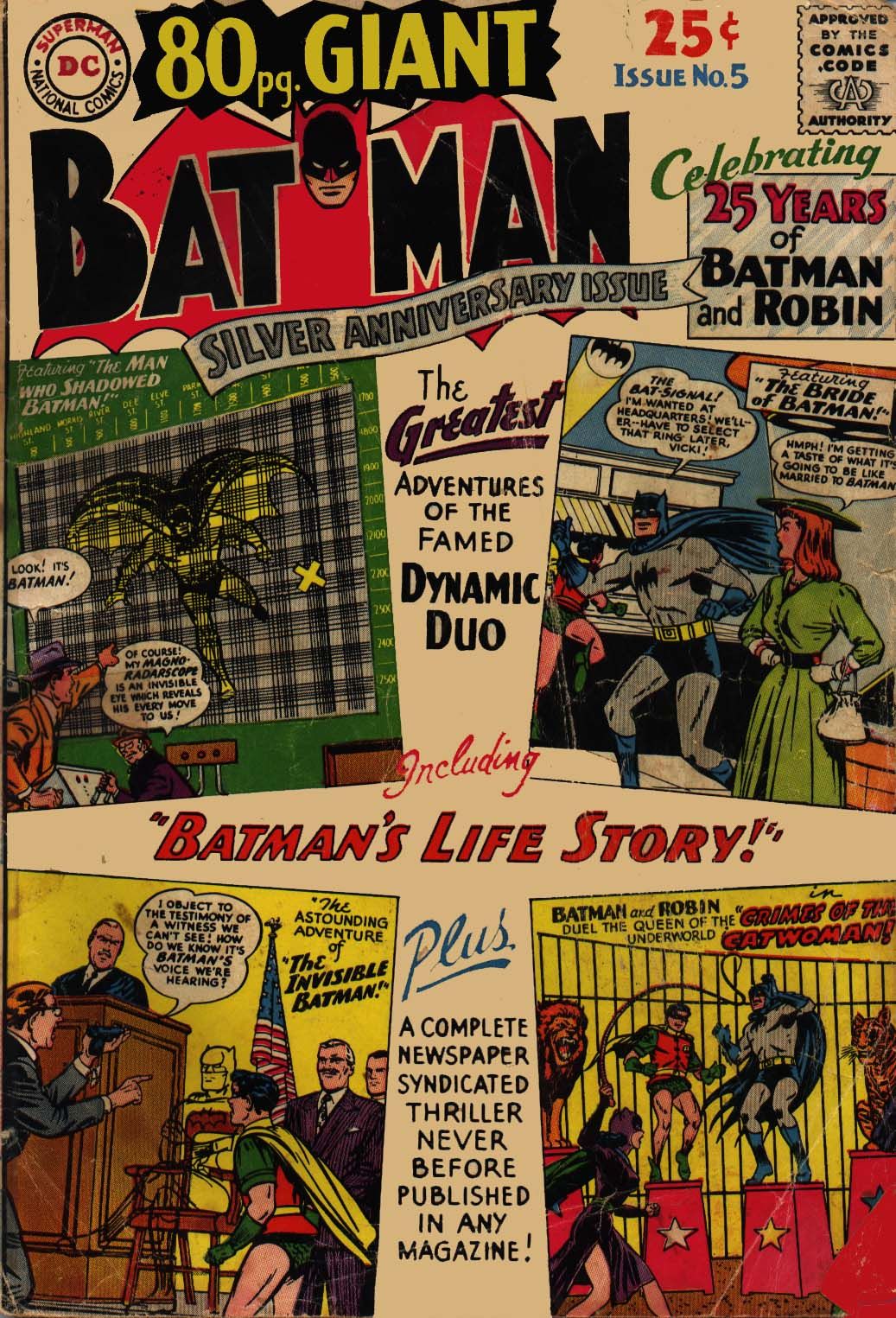

Now, less than a year earlier, in 1964, 80-page giant No. 5, it was dedicated to Batman and Robin…

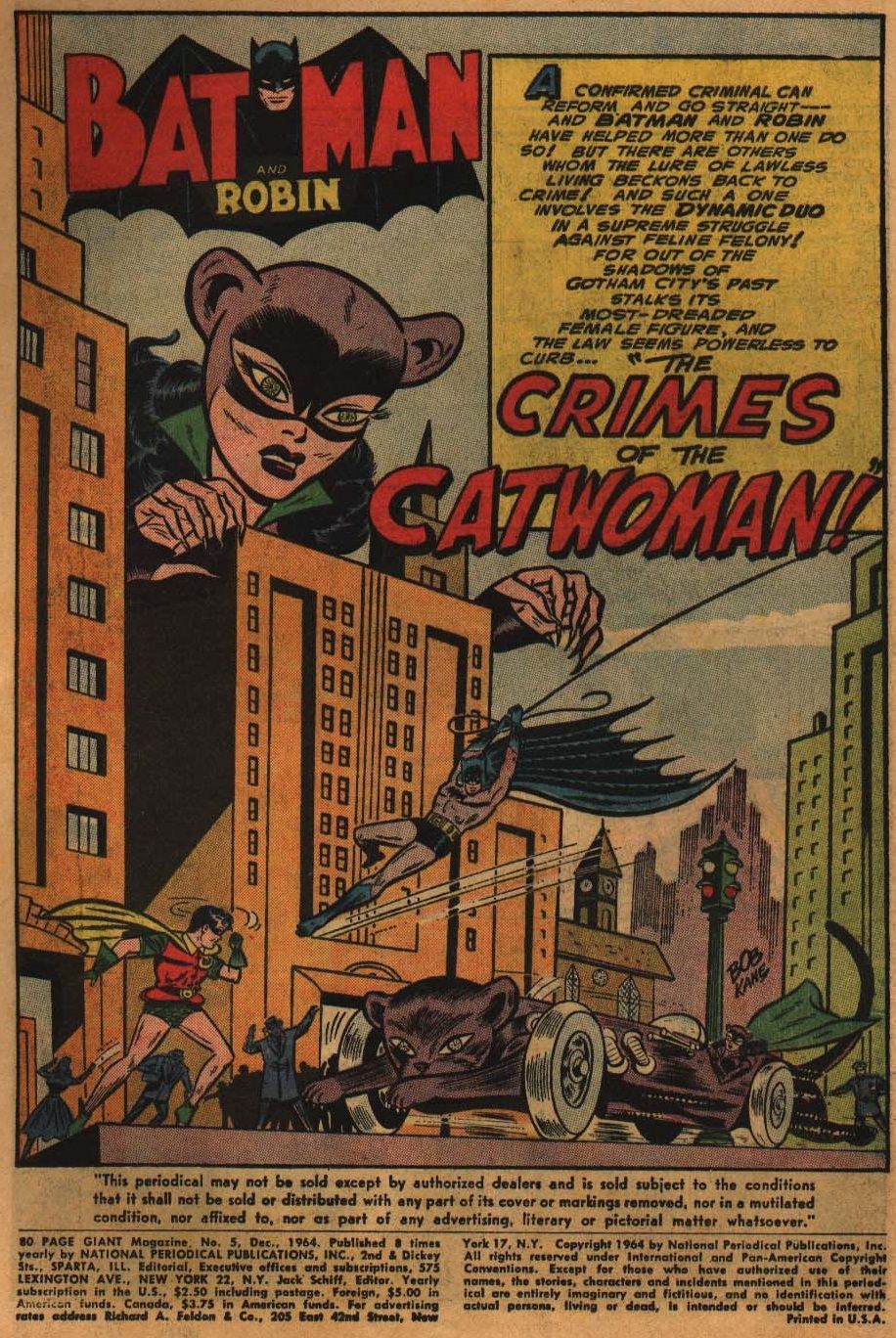

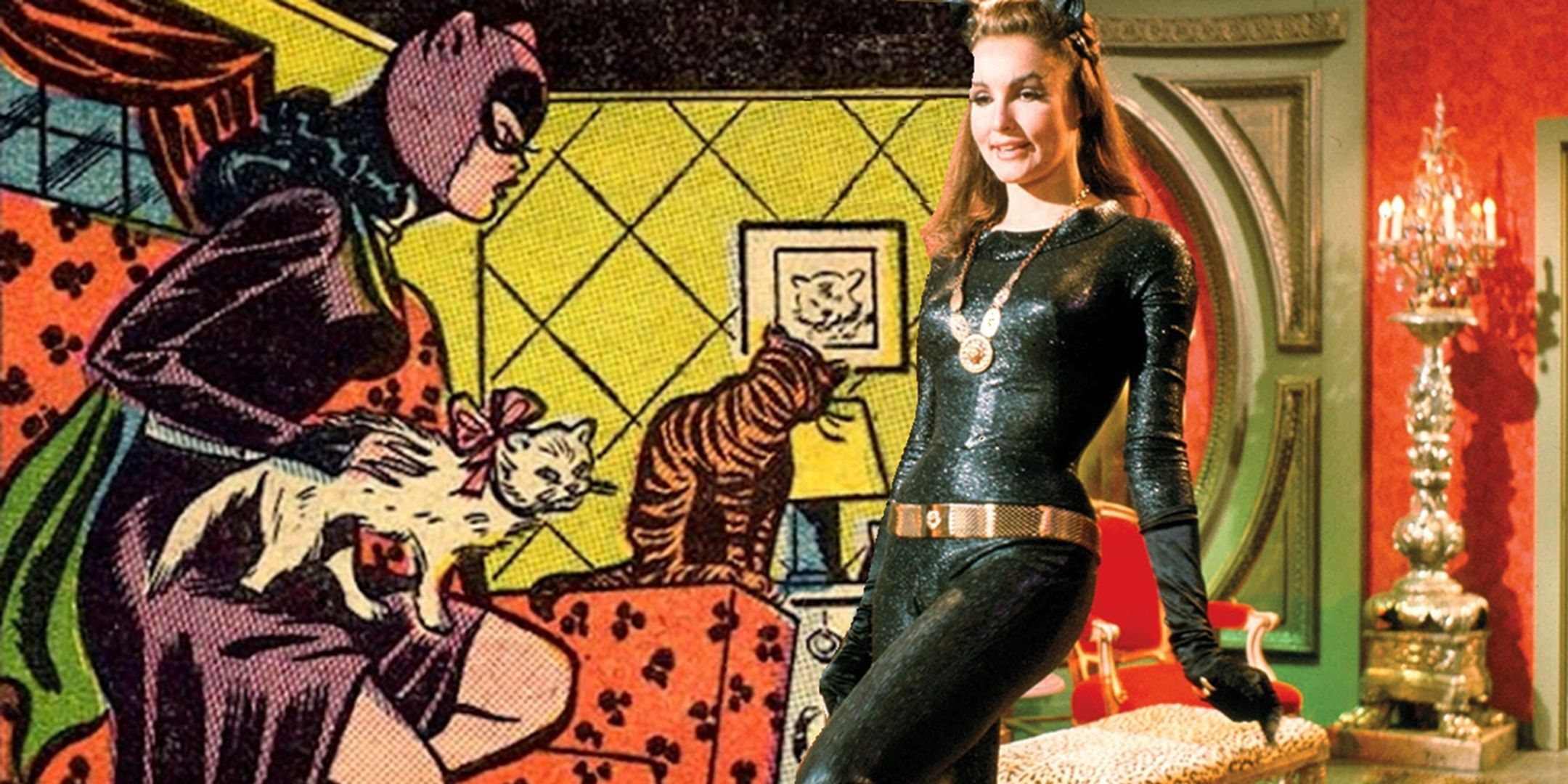

And a Catwoman story was the first to appear in the issue (1953’s “The Crimes of Catwoman!” by Detective comics #203, by Edmond Hamilton, Bob Kane and Charles Paris)!

Apparently, the authors have used the recent 80-Page Giants (the aforementioned Batman #176 was SPECIFICALLY cited, so I was willing to do that as a Comic Book Legends Revealed since I had more direct evidence), so I think it is very probably that Catwoman in this 80-page giant (reprint of one of her last stories before Comics Code), the ONLY COMIC BOOK IN WHICH SHE APPEARED for a decade, was the impetus for Catwoman’s appearance on the Batman TV series…

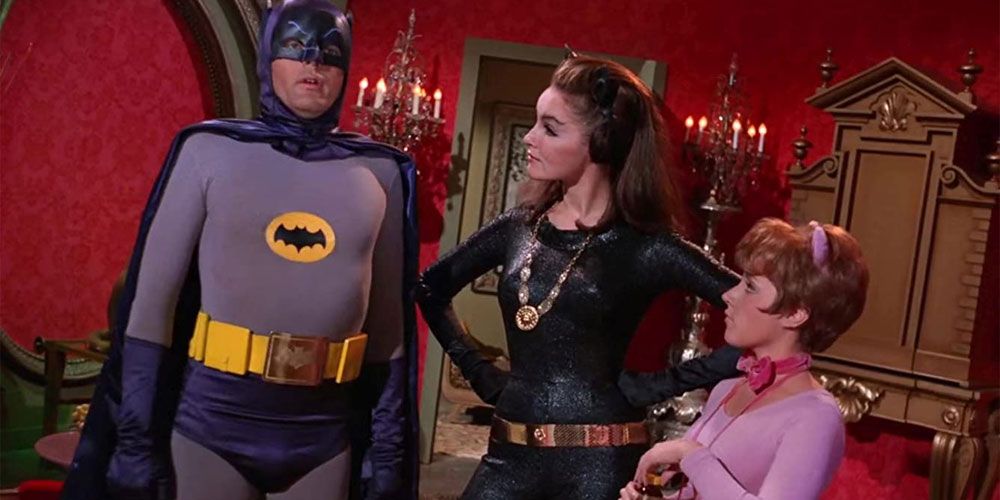

Julie Newmar obviously made it clear to everyone: “Oh yeah, Catwoman is great,” and she has been a mainstay of pop culture ever since.

If anyone knows of an interesting piece of comic book history that I should write about, send me a message at [email protected]!