Air Force War Officers to be important links in the digital war with China

The Air Force’s first cohort of warrant officers in 65 years already consists of experienced cyber and IT specialists. According to the officer responsible for their training, their training is aimed at teaching them to become the crucial link between soldiers and their superiors on technical issues.

“They are there to advise the operators, their commanders and higher-level leadership on how to use these (cyber and IT) capabilities and to be on the front lines and employ these capabilities themselves,” Maj. Nathaniel Roesler told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

The Warrant Officer program, unveiled in February, creates a new level of leadership in the Air Force – a way for soldiers to advance their careers without having to broaden and generalize their skills to advance into the noncommissioned officer ranks. It is also designed to equip the Air Force to compete with China and other major powers in the digital domain, where technical skills can be critical.

“As their careers progress, noncommissioned officers tend to develop more into organizational and personnel leaders, which broadens their skills,” said Roesler, commandant of the newly established Warrant Officer Training School at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama.

“We are a technical service. … We want our warrant officers to have a broad range of expertise,” he said. “They’re really there to develop a specific skill. As they advance in their careers and continue to specialize, we want to increase their level of knowledge and their ability to operate in the Air Force.”

The eight-week program developed by the Warrant Officer Training School is not only the Air Force’s first warrant officer program in more than 65 years (the last USAF warrant officers were hired in 1958), Roesler said – it is practically the first ever.

“Remember,” he said, “the Air Force inherited its warrant officer program from the Army,” so the school had to start from first principles when designing its training. It first derived five “core principles for warrant officers” – communicate, advise, influence, innovate and integrate – from the Air Force’s 24 core competencies for airmen.

It is no coincidence that “communicate” comes first.

Warrant officers of the 21st century, Roesler explained, must be “extraordinarily good at communicating under stress. They must be able to provide credible advice to their commanders who are leading these operations,” while also having the expertise to understand the skills they are using. The school aims to produce individuals who can work across agencies, he added.

“We’re not trying to make warrant officers better cyber operators,” he explained. “They come to us with those skills and years of hands-on experience. What we’re doing with them is making them the Air Force’s leading professional combatants, technical integrators and trusted advisors.”

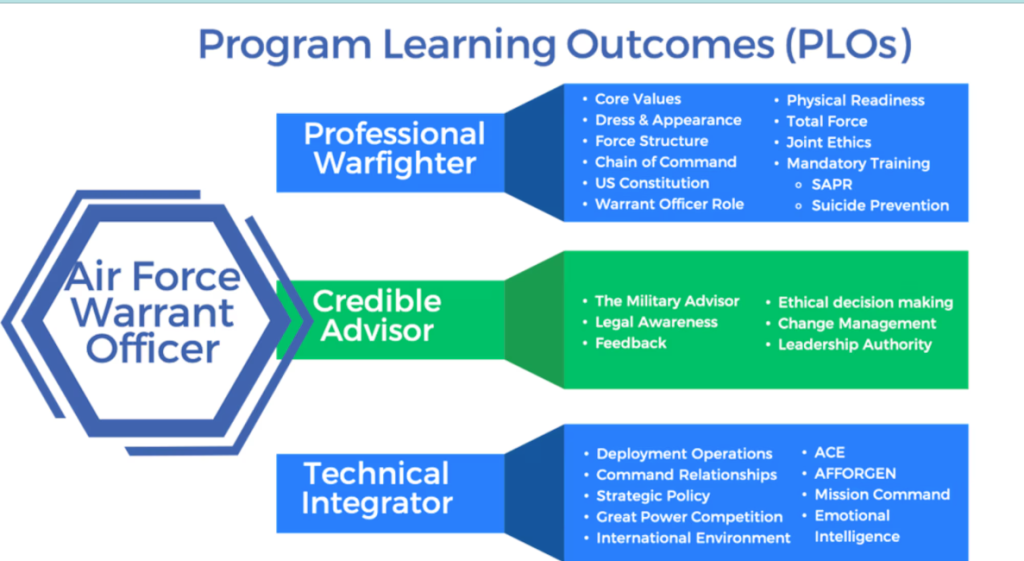

The three objectives he listed are the three “program learning outcomes” for the school. They, along with the five core principles, were derived from the 24 core competencies of the service.

The role of a credible advisor includes training in “legal awareness,” “ethical decision making,” and “change management.” Technical integrators must understand “deployment processes,” “great power competition,” and the “international environment.” “Emotional intelligence” is also required.

Professional soldiers must also learn about “dress and appearance,” “physical readiness,” and “core values,” as well as “force structure,” “chain of command,” and the “US Constitution.”

Some of those elements will be incorporated into a 10- to 14-day “induction program” designed for civilians with specialized skills that will feed directly into the warrant officer program should it be needed in the future, Roesler said.

“Right now, they all have a service qualification at level E-5 or higher,” he said of the school’s future trainees, but once the qualifications are proven, the school is ready to expand its capacity and also accept the so-called “street-to-seat” candidates.

In the meantime, Roesler explained, the training is also beneficial for the experienced NCOs of the first cohorts. “It’s always good to brush up on these skills: Air Force history, culture and chain of command. It’s valuable training for anyone, but especially for people who don’t have any Air Force experience,” he said.

The programs’ learning outcomes are key to “outcomes-based military training, which is what the Department of Defense does,” Roesler said. “They think about military training in a way that can be measured, trained and evaluated: how well we do and how well the soldier does in that training.”

This results-oriented approach was also based on research into optimizing human performance, according to Lt. Col. Andrew Wonpat, acting deputy cyber advisor to the Secretary of the Air Force.

“There’s this notion that we’re just going to run,” he said at AFCEA’s recent TechNet Cyber event in Baltimore. “We’re just going to run stronger, harder, faster and longer. But that’s not how it works. That’s not how Olympians train. That’s not how you identify, evaluate and develop Olympians. That’s not how industry develops its top performers, that’s not how the (Special Operations Forces or) SOF community does it.”

A key trait for warrant officers will be the right cognitive approach, Wonpat said: “Can you update your model to arrive at a new and novel solution when you receive new information?”

So far, the program is only for Air Force members and not Space Force members, but Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall has talked about expanding it to other specialties besides IT and cyber if the program is successful in those two areas.

“The great thing about the warrant officer program is that it’s new,” Wonpat said. “You don’t bring a lot of baggage or traditions with you. You don’t have to break a lot of ‘we’ve always done it this way’ rules.”

Wonpat said he worked with the Department of Defense’s CIO Workforce Innovation Team to understand the warrant officer program and “how it translates across the service or Department of Defense.”

The Air Force has announced two cohorts of 30 trainees each, Roesler said. The first will begin in October and finish in December, and the second will report for training in January and finish in March. A planning document posted online earlier this year and verified by Air & Space Forces Magazine said the Air Force plans to increase the number of graduates to 250 per year.

“We are fundamentally prepared to scale to whatever size the Air Force needs,” Roesler said. But he added that individual warrant officers would have an asymmetric effect because of their skills and their critical positions at the interface of new capabilities. “They will have a disproportionate impact,” he said.