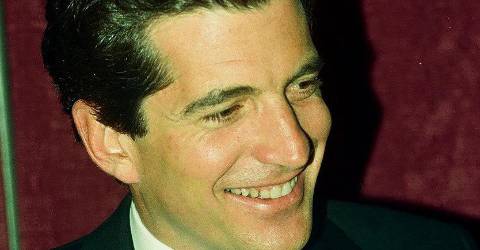

Remembering JFK Jr. 25 years after his tragic death

Has it really been 25 years already?

It was a hot and foggy day in July when I received a call from the business editor of the New York Post.

“John John’s plane is missing,” said Jon Elsen. He had left in his small private plane on the evening of July 16 with his wife Carolyn Bessette and her sister Lauren to spend his last day on earth before crashing into the sea about seven miles off Martha’s Vineyard.

And so, instead of going to celebrate my father’s birthday on July 17 with my oldest son, not quite two, and my wife, Pat, heavily pregnant with their second son, I drove back from Long Island to the Post office. On the way there, I passed the school where I had attended elementary school, where I had learned that President Kennedy had been shot in 1963 and that his brother, Senator Robert Kennedy, had been killed a few years later in June 1968.

I had a bad feeling about the fate of the last Kennedy, whom I had known during the years I covered him as a media columnist, a connection that began casually before he launched his political magazine. Georgewhen I watched him give a seminar at the Folio: Show at the Hilton Hotel called “How to Start Your Own Magazine.” (There was a time when it was cool to run a magazine.) The instructor told the class that they could start a magazine about anything except religion and politics. Kennedy was undeterred. He later brought George for what he hopes will be a bipartisan voice in American politics.

I caught up with him as he was going down an escalator at the Hilton. “Hey John, are you thinking about starting your own magazine?” He was polite but noncommittal. “If you ever decide to start a magazine, will you promise to tell me first?”

When he finally prepared to unveil his debut issue, I was already at Advertising Age, the media industry bible, and his first pre-publication interview went to me. The romantic in me always wanted to believe that John was fulfilling a vague promise he’d made a year earlier on an escalator between one Irishman and another. But in reality, this was probably at the urging of his boss, David Pecker, who later became notorious for owning the National Enquirer but was then CEO of Hachette Filipacchi Media, and who had agreed to fund Kennedy’s magazine to the tune of $20 million.

In the early days, Kennedy had a habit of filling in for Rose Marie Torenzio, his longtime assistant, who has now released a new book about her former boss, “JFK Jr.: An Intimate Oral Biography.” Co-written by Torenzio and Liz McNeil, editor-in-chief of People magazine, it is sure to be a bestseller.

Pecker knew Kennedy was a hot topic, but wanted less coverage of “the sexiest man in the world who is launching a magazine,” who had already been profiled in Newsweek, Esquire and New York without actually being interviewed. I remember asking him if he wanted to launch the magazine about politics as a springboard to a political career. And he had a quick answer. “There are easier ways to get into politics than launching a magazine.” A few months later, we followed up with a Guinness and a meal at Swift’s Hibernian Lounge just off the Bowery. I remember John arriving on a bicycle.

I moved to the Daily News shortly thereafter and reported that the attention – and advertising support – that George The magazine’s success, which had been a rousing success when it debuted in 1996, had waned. Kennedy always stayed off the cover, not wanting to capitalize on the Prince of Camelot’s fame, which would clearly have boosted sales. But he did write an editor’s note. And in one issue he appeared in a bathing suit draped in shadows, so that at first glance you’d think he’d posed nude. Circulation soared, but some advertisers thought the nude or nearly nude photo was a gimmick that didn’t suit a serious magazine.

Kennedy wrote to me after our story came out. “Naked is naked. This is not naked. Maybe you spent too much time in Catholic school.” I still have the letter. Good-natured humor was a Kennedy trademark.

Not long after, I moved on and became a Media Ink columnist at the New York Post. Kennedy duly acknowledged the move in another personal letter. He wrote, “Congratulations on your new job. I hope to do more with you in the future.” And he signed off, “Cheers. John (not John John) Kennedy.” It was July 1998. The following July, he was gone.

But when he died in the plane crash on July 16, George had a circulation of over 400,000 copies, more than the National review, The nation and that New Republic combined. However, the company had trouble maintaining the advertising support that a large, high-circulation glossy magazine needed to survive.

I firmly believe that Kennedy would have ultimately run for the U.S. Senate. And I believe he would have won by a landslide. And imagine where we would be today if someone with his kindness and humor were on the national stage. If he were alive, he would only be 63 years old. Twenty-five years after his death, I miss him more than ever.